This past week the Oisvorfer fielded complaints from two readers. Not about the content of the weekly parsha review; mistama they didn’t read it. Instead, both friends complained that there were no mazel tov shout-outs these past few weeks. They were correct: there were none to report. Ober we are back this week with three; here we go.

This past week the Oisvorfer fielded complaints from two readers. Not about the content of the weekly parsha review; mistama they didn’t read it. Instead, both friends complained that there were no mazel tov shout-outs these past few weeks. They were correct: there were none to report. Ober we are back this week with three; here we go.

Big mazel tov wishes to Yonina & Ephraim Stern and to Annette & Gary Kaufman, both families friends of the Oisvorfer for decades, upon the birth earlier this week of a baby boy born to their children Eliana and Ariel Stern. Mazel tov to both extended families all over the globe. Bris information will be forthcoming; all are invited. May baby Stern bring much and only joy to his parents, grandparents, great grandparents and everyone else.

Mazel Tov to our friends Alyssa and Chaim Winter upon the engagement (a few weeks back), and the party this evening, of their beautiful daughter Kara to Zvi Wolpe. Mazel tov to Zvi’s parents, Ramona and Richard Wolpe and to the entire extended Wolpe family. As well, a hearty mazel tov to Kara’s grandparents on both sides and to both extended families. May the young soon-to-be couple merit many decades of blissful marriage.

And…Mazel Tov to Esther and Baruch Weinstein upon the arrival of a baby granddaughter born to their daughter Tamar and (her husband) Mordechai Katz. Welcome to the world. Mazel tov to Mordechai’s parents, Civia and Elazar Katz. May your new daughter and granddaughter bring both extended families only joy. A special mazel tov shout out to great-bubby Bernice Weiss.

Raboyseyee and Ladies:

The Wall

Back in 2016, while then candidate Donald Trump was campaigning for President, at kimat every stop and during every stump speech, he promised to build a wall. Some say that wall-promise helped him win the election. Whether or not the wall was the deciding factor for most, ver veyst, ober one thing is zicher: Sadly his administration seems to have run into a wall instead of building one. The importance of a wall dates back several thousand years to Har Sinai (Mt Sinai) where the RBSO, at Revelation, gave the Yiddin a series of mitzvis. And wouldn’t you know, one of them -mitzvah #341 according to most- pertains to a wall. We shall discuss the significance of walls a bit later, ober let’s begin here.

Is it efsher meyglich (at all possible) that one can borrow funds from a chaver, mishpocho member or anyone else and halachically not be obligated to repay the loan? Avada we all know that the minhag ho’oilom is not to repay such loans ober is it kosher? Seemingly there is epes a mehalich (way) and as we explore Parshas Behar, a short but very interesting Parsha, we’ll circle around to this topic. Nu, brace yourselves: yet another double header will be read this coming shabbis and welcome as we say hello to Parshas Behar and Bechukoisei and good bye to Sefer Vayikro and Toiras Koihanim. Next week we’ll begin Sefer Bamidbar (the book of Numbers) and follow the Yiddin’s travails as they sojourned through the Midbar for 40 years. Ober before we discuss the practical applications of Shmita, Yoivel, Jewish slavery, loans to Yiddin, interest on those loans, helping your buddy out in his time of need and a few other interesting factoids all found in Parshas Behar, let’s quickly meet shmita and yoivel. Who are they, you ask? Nu it’s taka a shanda and a bizoyoin (shameful and disgraceful) to even hear the question and only an oisvorf would taka dare ask. Shmita and yoivel are concepts – mitzvois, heylige ones that the RBSO himself gave over (apparently) at Har Seenai. So why repeat them here? We can efsher kler (think) that the Yiddin were so mesmerized with the thunder sound and light show, with the RBSO’s presence on the mountain, and especially when they heard how their lifestyles would need to quickly change following the declaration of the five loi sah-says, especially the one specifically outlawing the coveting of a chaver’s wife and all else that belongs to a chaver, that they mamish weren’t paying attention when the RBSO instructed them about the laws of shmita and yoivel. And as a service to the (less than) choshovo readers, who were too busy with other narishkeyt while the rebbe was, when not busy beating the living daylights out of you, explaining shmita and yoivel, let’s do a quick review.

Is it efsher meyglich (at all possible) that one can borrow funds from a chaver, mishpocho member or anyone else and halachically not be obligated to repay the loan? Avada we all know that the minhag ho’oilom is not to repay such loans ober is it kosher? Seemingly there is epes a mehalich (way) and as we explore Parshas Behar, a short but very interesting Parsha, we’ll circle around to this topic. Nu, brace yourselves: yet another double header will be read this coming shabbis and welcome as we say hello to Parshas Behar and Bechukoisei and good bye to Sefer Vayikro and Toiras Koihanim. Next week we’ll begin Sefer Bamidbar (the book of Numbers) and follow the Yiddin’s travails as they sojourned through the Midbar for 40 years. Ober before we discuss the practical applications of Shmita, Yoivel, Jewish slavery, loans to Yiddin, interest on those loans, helping your buddy out in his time of need and a few other interesting factoids all found in Parshas Behar, let’s quickly meet shmita and yoivel. Who are they, you ask? Nu it’s taka a shanda and a bizoyoin (shameful and disgraceful) to even hear the question and only an oisvorf would taka dare ask. Shmita and yoivel are concepts – mitzvois, heylige ones that the RBSO himself gave over (apparently) at Har Seenai. So why repeat them here? We can efsher kler (think) that the Yiddin were so mesmerized with the thunder sound and light show, with the RBSO’s presence on the mountain, and especially when they heard how their lifestyles would need to quickly change following the declaration of the five loi sah-says, especially the one specifically outlawing the coveting of a chaver’s wife and all else that belongs to a chaver, that they mamish weren’t paying attention when the RBSO instructed them about the laws of shmita and yoivel. And as a service to the (less than) choshovo readers, who were too busy with other narishkeyt while the rebbe was, when not busy beating the living daylights out of you, explaining shmita and yoivel, let’s do a quick review.

Says the heylige Toirah: the RBSO spoke to Moishe b’Har Sinai (at Mount Sinai) saying… the land shall rest as a Sabbatical to Hashem. “When you come to the land that I am giving you, the land must be given a rest period, a Shabbis to G-d.” What’s taka pshat that the land gets tired? Though a few of us know a thing or two about plowing, if you chap, are we farmers? Can we chap what it means that the land needs a rest? We cannot! Ober, if the RBSO says it’s so, who are we to argue? Veyter.

For six years you may plant your fields, prune your vineyards, and harvest your crops, but the seventh year is a Shabbis of Shabossim for the land. It is G-d’s Shabbis during which you may not plant your fields, nor prune your vineyards. The sabbatical year of shmita is called a “Shabbis,” and indeed, just as Shabbis is a day of rest after six weekdays, shmita is a year of rest after six years of work. Shmita is seemingly a mitzvah unique to the land of Israel. In other words, the land does not get tired outside of Israel. Shoin!

Now that you’re all shmita experts, let’s move on to another amazing concept: yoivel! The yoivel mitzvah follows immediately after shmita and is explained as follows. Yoivel means Jubilee and the yoivel year is known as the jubilee year. Says the heylige Toirah: “You shall count seven sabbatical years, that is, seven times seven. The period of the seven sabbatical cycles the land an emancipation [of slaves] for the entire populace. This is your jubilee year, when each man shall return to his hereditary property and to his family.” Got that? No? Noch a mol.

During yoivel, the land may not be worked; crops are not harvested; and produce is shared by all. Moreover, the heylige Toirah (elsewhere) describes two additional aspects of yoivel. Ershtens (firstly), the land reverts back to its original owner. And who might that be? What if he’s no longer alive? Nu, in that event, the land reverts back to its ancestral owners. And who are they? All the land in Israel is redistributed to the descendants of those who initially conquered and possessed it. Mistama we’ll have to dig them up! Mistama also, for most of you, this particular halacho is not a major concern, nor to most real estate investors, but should it be ignored? Also, on yoivel, the slaves go free.

And if ever there was, or is a mitzvah, where the RBSO says to test Him, it’s yoivel. Says the heylige Toirah (Vayikro 25:20), azoy: “And if you will ask, what will we eat (as the land remains fallow) in the seventh year? After all, we must not sow, nor gather in our produce,” Nu, the RBSO assures us that in year six of the cycle, the farmer will reap an overabundance of whatever he is growing. He does? Yes, in the very next posik (25:21) He tells us “I will then order My blessing for you in the sixth year, and (the land) will yield produce for three years’ (use).” So much so that he will have enough to sustain himself and the mishpocho for part of year six, seven and even eight. How all this worked? Only through a miracle the RBSO promises, and if He promises, why worry? Nu, is there better way to test the RBSO than to see if He in fact delivers in year six? Does any other god offer such guarantees? Not! And if one does, can he deliver? Also not!

And if ever there was, or is a mitzvah, where the RBSO says to test Him, it’s yoivel. Says the heylige Toirah (Vayikro 25:20), azoy: “And if you will ask, what will we eat (as the land remains fallow) in the seventh year? After all, we must not sow, nor gather in our produce,” Nu, the RBSO assures us that in year six of the cycle, the farmer will reap an overabundance of whatever he is growing. He does? Yes, in the very next posik (25:21) He tells us “I will then order My blessing for you in the sixth year, and (the land) will yield produce for three years’ (use).” So much so that he will have enough to sustain himself and the mishpocho for part of year six, seven and even eight. How all this worked? Only through a miracle the RBSO promises, and if He promises, why worry? Nu, is there better way to test the RBSO than to see if He in fact delivers in year six? Does any other god offer such guarantees? Not! And if one does, can he deliver? Also not!

As you can imagine, volumes are written about these quite amazing pisukim in the Toirah and avada there’s plenty of discourse as to what they mean. Says the heylige Gemora (Ayrachin 32b) azoy: yoivel is only in effect when all the Yiddin are residing in the land of Israel. In other words, yoivel is only declared if all the Yiddin are living in the land of Israel. If they’re not, no yoivel. Adds the RambaM and a majority of other commentators: this is true for the previously stated mitzvah of shmita as well. Gishmak; and what does that mean for us in 2017 as Yiddin are dispersed all over the world? No shmita and no yoivel. well, at least none that are biblically mandated. Ober (but) mistama for business purposes, bazman hazeh (in today’s times) we understand this to mean that only a majority of the world’s Yiddin need to live there. And even though less than 50% of the Yiddin live there and even though min Hatoirah (biblically), there is no mitzvah of shmita or yoivel for that matter, nonetheless, and as suggested earlier, for reasons that are unknown to us but of course known to the Rabbis that declared it to be otherwise, they do enforce shmita in Israel today. What does enforcement entail? Nu, chap nisht; soon we’ll learn.

Ok- now that you learned what shmita and yoivel are, mistama you’re trachting (thinking): what do these concepts have to do with you and me? Are we farmers or slave masters? Are any of our chaverim? Are you planning to buy a farm or a slave anytime soon? Isn’t it a fact that the only farming you taka know and understand is plowing fertilizing and seeding if you chap, and that none of those are shmita related? Shoin. And aren’t we ourselves slaves, if you chap, to our farming habits?

Though parshas Behar is most well known for its introduction to, and discussions on shmita (Sabbatical) and yoivel (Jubilee), over in perek 25, pisukim 29-30 we find the following regarding a wall which surrounds a city. Lommer lernin inaveyning. Says the heylige Toirah, azoy: “If a man sells a dwelling house in a walled city, it may be redeemed until a year has elapsed since the sale; the redemption period shall be a year. If it is not redeemed before a full year has elapsed, the house in the walled city shall pass to the purchaser beyond reclaim (permanently) throughout the ages; it shall not be released in the yoivel (Jubilee).”

And what does all that mean? Why is the RBSO telling us about a walled city? And why should a legitimate real estate transaction be unwound in year one? Nu, let’s find out. There is seemingly a mitzvas ah-say (positive commandment) which tells us that if someone sells, or even donates, a house in the land of Israel, in a city that was surrounded by a wall dating back to the time when Yihoishua led the conquest of what was then known as the land of Canaan which he conquered and then doled out to the holy shevotim in accordance with their size and as delineated elsewhere in the heylige Toirah, that very house may be, or should be, redeemed during the first year of the transaction. In plain English: the status of a walled city is determined by one thing only: whether or not it had a wall around it at the time Yihoishua first conquered and then allocated its land to the shevotim.

And what does all that mean? Why is the RBSO telling us about a walled city? And why should a legitimate real estate transaction be unwound in year one? Nu, let’s find out. There is seemingly a mitzvas ah-say (positive commandment) which tells us that if someone sells, or even donates, a house in the land of Israel, in a city that was surrounded by a wall dating back to the time when Yihoishua led the conquest of what was then known as the land of Canaan which he conquered and then doled out to the holy shevotim in accordance with their size and as delineated elsewhere in the heylige Toirah, that very house may be, or should be, redeemed during the first year of the transaction. In plain English: the status of a walled city is determined by one thing only: whether or not it had a wall around it at the time Yihoishua first conquered and then allocated its land to the shevotim.

What’s the connection? Shoin: during yoivel, land goes back to its ancestral inheritance; such ancestral inheritance began only at the time of Yihoishua when the Yiddin first came into, and received their portion of such inheritance. Got that? Veyter. Ober what is the significance of a walled city dating back to the days of Yihoishua and his conquest? Other than the fact that Rochov, the inn-keeper, if you chap, who may or may not have been running a house of ill repute and whose one house was located within a walled city as described in Sefer Yihoishua (Book of Joshua), ver veyst? So happens that Rochov was also one of Yihoishua’s conquests as he married her. Are these concepts related? However, if the house was not redeemed (brought back into the estate of the seller) during the first year, the buyer is no longer obligated to sell it back (or give it back in the case where it was donated) and he, the buyer may keep the house even if yoivel, the year of Jubilee, the year when many purchases are unwound, and when many a house and land are returned to their ancestral family. In other words: once a full year passes, though it’s suddenly yoivel, the buyer keeps the house and his purchase is exempt from the laws of yoivel.

And why taka may a transaction in which a house within a walled city was either sold or donated be unwound? Says the Rambam, azoy: because selling or having to give away a house within a walled city dating back to the times of Yihoishua must have been a difficult decision for the seller, one that mistama embarrassed him. Likely he made the sale when he was down on his luck, mistama desperate to raise cash to pay off loans or other bills. And because such a sale was embarrassing to him, therefore the heylige Toirah, with compassion, commands that such a person have a second chance within the first year to redeem his own land. However, this right or option, expires after year one, and come what may, after year one, even yoivel which cancels many a land lease, purchase, and other debts -as we shall see below- cannot cancel the transaction. Exactly why and how this particular mitzvah entails only cities that were walled in the days of Yihoishua, ver veyst. Was a person less embarrassed to have sold his house to get out of debt were he living in a city without walls? The bottom line: the existence of a wall has consequences. So says the heylige Toirah and so says (lihavdil) unzer (our) president.

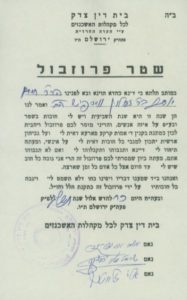

Yoivel cancels other debts? OMG! What are Yiddin to do about debtors telling their creditors they no longer owe them money – that their loans are cancelled- due to yoivel? Would people loan each other money with yoivel lurking? It’s mamish shreklich and say it’s not so. Nu, not to worry: why not? Because avada our sages of old -mistama a few in the money lending business themselves- chapped that society would come to a grinding halt and stepped in with a fix. This fix, known today as ‘the pruzbil’ was enacted to overcome the calamitous affects of yoivel were it to be practiced as described in the heylige Toirah. Shoin. What the hec is a ‘pruzbil’ and how does it work? Halt zich eyn (keep your pants on); we’ll get to that in a moment.

Nu, many of you avada know that Yirusholayim where real estate prices are sky high, is in fact a walled city, and mistama you’re thinking that this law applies also to Yirusholayim. Oib azoy (if that’s the case, what will become of your real estate purchases? Of your multi-million dollar apartments which are used as many as 1-15 days each year? After all, isn’t Yirusholayim a walled city? Zicher it is and taka in our times, over in Yirusholayim, as in other walled cities, they read the Migilah on Purim one day later as is the law. Ober says the Rambam and others, that though Yirusholayim is in fact walled, it is excluded from the list of cities where land sales may be redeemed in year one. Sales within Yirusholayim may not be unwound in year one: its status is that of an unwalled city when it comes to real estate transactions. Ober should one be selling real estate in other cities in our times? And must we pay our mortgages if yoivel approaches? And the answer is yes: this particular law of debt cancellation, and many others, are only valid during times when both yoivel and shmita are in effect based on biblical law and today, as we all know, they are not. When will real estate revert back to Toirah times? When the Moshiach arrives. When is that? When people stop speaking loshoin horo (badmouthing one another), and or, observe two consecutive shabosim without desecrating it. When will that be? Ever? Ver veyst?

Nu, many of you avada know that Yirusholayim where real estate prices are sky high, is in fact a walled city, and mistama you’re thinking that this law applies also to Yirusholayim. Oib azoy (if that’s the case, what will become of your real estate purchases? Of your multi-million dollar apartments which are used as many as 1-15 days each year? After all, isn’t Yirusholayim a walled city? Zicher it is and taka in our times, over in Yirusholayim, as in other walled cities, they read the Migilah on Purim one day later as is the law. Ober says the Rambam and others, that though Yirusholayim is in fact walled, it is excluded from the list of cities where land sales may be redeemed in year one. Sales within Yirusholayim may not be unwound in year one: its status is that of an unwalled city when it comes to real estate transactions. Ober should one be selling real estate in other cities in our times? And must we pay our mortgages if yoivel approaches? And the answer is yes: this particular law of debt cancellation, and many others, are only valid during times when both yoivel and shmita are in effect based on biblical law and today, as we all know, they are not. When will real estate revert back to Toirah times? When the Moshiach arrives. When is that? When people stop speaking loshoin horo (badmouthing one another), and or, observe two consecutive shabosim without desecrating it. When will that be? Ever? Ver veyst?

Nu, mistama you’re anxious to quickly move right into Bechukoisei and get scared straight as the RBSO lays out the various punishments awaiting us for being such active farmers, ober raboyseyee be forewarned: you’re not at all going to be happy when you hear what Bechukoisei has in store for us, and the heylige Oisvorfer strongly suggests we stick to shmita and yoivel because in reality this parsha gave birth to two of the bigger legal loopholes, kimat as big as michiras chometz to the unsuspecting goy, we taka enjoy in the entire Jewish religion. Would we still be orthodox without loopholes? Could we? Mistama not! Nu, geloibt der Abishter (thank the RBSO) we have loopholes and they’re sanctioned and kosher. Mamish legal? Yes! And now that you’re paying attention – let’s taka introduce them, ober first, let’s learn this additional halacho of shmita.

Shmita nullifies any outstanding debts. Come again! Yes, at the end of a shmita year, all loans or debts between Jewish people (men or women) that are due before Rosh Hashono, are cancelled. What? Did you just read that you can borrow money from your best friend, wait seven years (less if you borrowed funds closer to shmita) and then tell him you’re not paying him because his loan expired due to shmita? Indeed you did. This is called shimitas kisaofim (a debt wipe-out, if you will). Moreover, there is also a loi-sah-say (negative prohibition) that is violated if someone requests payment after shmita for loans initiated before the shmita year and this includes debts resulting from monetary loans as well as those incurred from borrowing items that have been consumed. In other words: not just aren’t you getting paid but you get an avayra just for asking for your money. Nu, you got to love it. Nice guys do taka finish last or in the case where their loans are wiped out, are taka finished!

Shmita nullifies any outstanding debts. Come again! Yes, at the end of a shmita year, all loans or debts between Jewish people (men or women) that are due before Rosh Hashono, are cancelled. What? Did you just read that you can borrow money from your best friend, wait seven years (less if you borrowed funds closer to shmita) and then tell him you’re not paying him because his loan expired due to shmita? Indeed you did. This is called shimitas kisaofim (a debt wipe-out, if you will). Moreover, there is also a loi-sah-say (negative prohibition) that is violated if someone requests payment after shmita for loans initiated before the shmita year and this includes debts resulting from monetary loans as well as those incurred from borrowing items that have been consumed. In other words: not just aren’t you getting paid but you get an avayra just for asking for your money. Nu, you got to love it. Nice guys do taka finish last or in the case where their loans are wiped out, are taka finished!

The bottom line is that this shmita is no joke as it mamish wipes out loans that you gave in good faith hoping to be repaid. And why shouldn’t it? Who says that just because you were nice enough to advance a chaver (friend) much needed funds that you’re entitled to get repaid? Don’t you know that no good deed goes unpunished? And this isn’t just a minhag (custom) but a din. Want more bad news? Bazman Hazeh (in our times), even when the laws of yoivel are not applicable (according to most Halachic authorities), the mitzvah of Shemitas Kesafim (rabbinic only) remains in effect. And taka why? Says the Gemora: this was instituted so that these laws would not be forgotten from Israel. Gishmak! Moreover, this Mitzvah applies in Israel and in chutz Lo’oretz (here), since it is an obligation dependent on the person (Gavrah) and not on the land (Adamah). Yet another loophole, ver veyst?

Nu, what to do about this halacha? How do we operate? Would people lend money even for interest (we’ll get to that soon) in year six (or earlier) if they understood that their loans are subject to being wiped out in year seven? Avada nisht! Ober not to worry because Toirah/shmoira: the Rabbis understood that business is business and that the halacho of shmita and loan cancellation would mamish shut down the money lending business and efsher the gantze (entire) economy. Who would support their local rabbis if they weren’t getting their loans repaid and couldn’t collect interest? Nu, when the rabbis’ parnosa (livelihood) is potentially affected, they came up with one of the more clever loopholes ever created and named it the Pruzbil. And Chasdei Hashem (through the kindness of the RBSO), halocho makes use of “evasions” of the law in various different realms.

And who says that one has to lend money to those in need? Nu…the heylige Toirah says so in discussing shmita (Devorim 15:2; 9-10) and let’s learn the pisukim. And this is the law of the Shemitah; to release the hand of every creditor from what he lent his friend; he shall not exact from his friend or his brother, because the time of the release for the L‑rd has arrived … Beware, lest there be in your heart an unfaithful thought, saying, “The seventh year, the year of release is approaching,” and you will begrudge your needy brother and not give him… You shall surely give him, and your heart shall not be grieved when you give to him; for because of this the L‑rd, your G‑d, will bless you in all your work and in all your endeavors.

Nu, as you can see, the RBSO was worried about us having unfaithful thoughts, if you chap, even about money issues. Says the heylige Gemora: about a century before the destruction of the second Beis Hamikdash (Temple) a man named Hillel the Zoken (the elderly) came up with mamish a givaldige loophole, one of many that allow us Yiddin to survive on a daily basis. After all, the heylige Toirah does state Vo’chai Bo’hem (and you shall live by them) and avada we translate that to mean that if a law makes life so unbearable, we may find a way around it. Anyway, Hillel saw that people were avoiding lending, and because he didn’t want them to commit the avayro of not lending to those who needed help (a sin mamish described above), as the shmita year approached, he came up with this brilliant chap (novel idea).

How does it work? Like a loophole should! The Toirah tells us that only private debts are cancelled by shmita: “He shall not exact from his friend or his brother.” Read those words again. If, however, one owes the court (i.e., the community) money, shmita does not affect the loan. Based on the wording of the Toirah, Hillel instituted the “pruzbil“: a mechanism by which debts are magically transferred from the individual to a Beis Din (religious court). By making a pruzbil, one makes his private debts public – and therefore redeemable. Want to go public? A simple Pruzbil does the trick. Exactly how the funds are collected by the Beis Din and how they are repatriated to the original lender, nu, that part remains somewhat shrouded in mystery ober es lust zich farshteyn (it is understood) that after the proper vig is given to Beis Din, the rest makes its way back somehow. Actually, as the Oisvorfer understands the mechanics: once you declare that it belongs to the beis din (with the pruzbil), you can actually collect it yourself. And as to why Hillel was allowed to enact this loophole, we are taught that there was a pressing need. As an aside, one may not invoke the ‘pressing need’ defense when asked by the eishes chayil, once chapped, why he was chapping. Mistama a concept similar to hefsed meruba (big losses) under which, one day soon, shuls, on shabbis and other times, will be able to swipe and process pledges at an appeal. This would zicher increase collections.

Avada you’re totally bewildered at Hillel’s actions, for who empowered him to go against what the heylige Toirah demands? And as you can only imagine, the Gemora has lots to say on this inyan. And not just the Gemora, for generations since, they’re still discussing Hillel’s bold move and its mechanics. In fact Toisfis (a commentator on the Gemora) states that there was mamish no concept of shmita or yoivel during the 2nd Beis Hamikdash because a majority of the Yiddin were living outside of Israel, a concept we covered earlier. Hence Hillel did nothing wrong. Others say Hillel was not the creator of this loophole altogether and that he was merely given credit because he publicized an already existing loophole in the Toirah which allowed private debt to be converted into court debt. In other words: Hillel, mistama the first Jew in that position, was acting like the Federal Reserve during a crisis in order to allow the banking system to work for the Yiddin. Shoin, who should it work for, the goyim? Of course you’re now wondering what will happen if and when the Moshiach arrives. Will we need loopholes if they bring back shmita and yoivel? Is Hillel coming back? Ver veyst?

And listen to this vichtiger nikuda (important point). There are various types of debts which do not require a pruzbil and can be collected after shmita even without the paperwork. Lemoshol (by way of example), these include debts which arise as a penalty or fine — such as the money a man must pay his victim for rape or seduction. You see from this that the sages knew that even back then the menner (men) were shlecht (bad boys) and had to make provisions for their victims to be able to collect. Also, a woman’s kesubah (marriage contract) may be enforced. There are a few others ober once you heard rape and seduction, does anything else matter? Zicher nisht!! Go look them up. Ginig (enough) on the Pruzbil, let’s bikitzur (in short) cover the next beautiful loophole in this week’s parshas, the famous Heter Iska. Yes, you heard that correctly: the Heter Iska.

We learn this week that the RBSO wants us, in fact He exhorts us, to assist other Yiddin financially, and prohibits us from charging interest on these loans. Says the Chofetz Chaim that every Yid should grant another Jew an interest-free loan, and recommends that each person apportion some tzedakah money for granting such loans. It is perfectly permissible, however, for a person to invest money in a Jewish business, and to share proportionally in whatever profits or losses there may be.

Says the heylige Toirah azoy: (25:35): “If your brother near you becomes poor and is unable to support himself-you shall strengthen him.” Seemingly what is meant by ‘strengthening him’ is, according to Rashi and many others, an obligation on those who can, to be sensitive to other people and pay attention to their problems and needs. Moreover, we may not wait for our friend to fall down and hit bottom; at that point it’s efsher too little and too late. Instead, the RBSO instructs us to offer assistance to our chaver (buddy) as soon as we see that he’s in trouble. It’s at this point, when it is still relatively easy to help a chaver, that we must act to help him regain his financial equilibrium. This assistance can be in the form of a loan, gift, advice or, ideally, a job. The point is to not to stand on the sidelines: offer assistance!

Efsher you’re klerring if the Yiddin, upon hearing these instructions, weren’t themselves wondering how they might best be able to fulfill this mitzvah in the midbar while under the direct daily and nightly supervision of the RBSO and also eating a steady diet of Mun; did some have more than others, ver veyst? Ober said The Sokatchover Rebbe azoy: this mitzvah is not limited to financial needs. It also applies to any need a person has that requires strengthening and encouragement from others. In the desert people had different levels of faith and trust in the RBSO. There were those people whose faith was very strong, others still wavering. This mitzvah mandated that those people who possessed strong faith had to, through their words, strengthen and encourage those people whose faith was weak. They needed to inspire their friends with words to get them through the difficult times.

Ober to accommodate the over 99% of Yiddin that can’t/don’t give such loans and help where really needed, nu-it’s time to introduce for a second time – the heter iska. Nu, zog shoin (tell me already) what is it? Today all that is necessary to circumvent the law of not charging interest to another Yid, is to sign a heter iska , some kind of document ‘invented’ by our Rabbis that converts a loan into a business partnership. This is avada very similar to another “rabbinic loophole”, that of mechiras chometz, one we mentioned above.

Seemingly, the idea of the heter iska arose way back in the seventeenth century, and expanded to enormous proportions over the last hundred years, despite its inherent halachic difficulties, ober as we stated above: business is business and seemingly, there was little interest (pun intended) in conducting business without real interest. It works like this.

Seemingly, the idea of the heter iska arose way back in the seventeenth century, and expanded to enormous proportions over the last hundred years, despite its inherent halachic difficulties, ober as we stated above: business is business and seemingly, there was little interest (pun intended) in conducting business without real interest. It works like this.

In a heter iska, the “lender” and the “borrower” turn into “investor” (capitalist) and “businessman.” Thus, it is noted that all the documents mentioning the terms “borrower” and “lender” actually mean “investor” and “businessman.” Shoin: a new title and you’re good to conduct business. The investor gives money to the business, and the businessman is supposed to invest the money in a business that yields profits. The profit and loss derived from the money is divided equally between the investor and the businessman, except for the small salary that the businessman takes for his work. The important point in the agreement is that the investor cannot know exactly how much the businessman profits from the business, and so the parties agree among themselves that the businessman is required to prove the truth of the figures presented by him. If the businessman is unable to prove to the investor how much money he earned, he must pay him demei-hitpashrut, at the rate of interest. Practically speaking, the businessman (i.e., the borrower) is unable to prove how much his business profited or lost, and therefore he must pay the investor (the lender) the agreed upon demei-hitpashrut. In other words: a givaldige loophole being used bazman hazeh (in our times) on a daily basis. Banks opening in Jewish neighborhoods, have this form handy. No more toasters or corning ware: today with your loan, you get only a heter iska! This is emes, mamish! Nu, the Oisvorfer asks: were our sages not mamish brilliant? Did they not sit and ponder and figure out how to make life easy for the Yiddin back then? We need those sages back; seemingly today’s, for the most part, sit around and try to figure out how to make life miserable for us.

Shoin, we’re kimat out of time and space ober a few words on parshas Bechukoisei and they come with a strict warning: If you suffer from nightmares and or any other sleep disorder, efsher you’re an occasional bed wetter, or stam have trouble falling asleep, do not read this parsha. Raboyseyee: parshas Bechukoisei is not for the faint of heart.

Though the toichocho (admonitions/curses) found in this parsha is considered the “smaller” of the two found in the heylige Toirah (the other, in parshas Ki Sovoi), it’s still not too pleasant to read and hear. Accordingly, the Baal Kora (reader) reads this section of the heylige Toirah in an undertone, at times barely audible. All this got the Oisvorfer thinking azoy: if the RBSO wanted to warn us about what may lie ahead for the sinners and if the Mishna taka established that this reading is so critically important that we cannot make any hofsokos (stops) during its reading, why does the baal Koirah read them in a soft undertone so that barely anyone can hear him? Does this make sense to you? If we can’t hear them, maybe they’re not meant for us? Ver veyst?

Seemingly and despite repeated warnings, the Yiddin, as we will learn beginning next week, did not necessarily pay heed to these warnings. They were and still remain a thick skinned people. Despite all the dire warnings in this week’s parsha and again repeated later in Sefer Devorim, the Yiddin seemingly shook them all off. Isn’t it emes that throughout history, the Yiddin didn’t learn much of a lesson from these curses? They lost the Beis Hamikdash twice, were exiled from the land, and experienced innumerable other pogroms and massacres and yet they continued to go about life without an accounting. Nu, the Oisvorfer should not be giving mussir, if you chap. The parsha is scary enough. Let’s stay strong!

Chaazak, Chaazak, Vinischazek: a Gittin Shabbis!

The Heylige Oisvorfer Ruv

Yitz Grossman