This week we begin with two givaldige shout outs. First, with mazel tov wishes to Beth and Yehuda Honig upon the aurfuf this coming shabbis and the wedding this coming Monday, of their son Josh (OMG) to Natalie Wizman, she the daughter of Dailit and David Wizman of Los Angeles, CA. Didn’t we just attend Josh’s bris a few years back? It feels like mamish yesterday that the Oisvorfer along with his eishes chayil attended the wedding of Beth and Yehuda, one week mamish to the day following their own wedding.

And in keeping with one of the major themes of this week’s parsha, being a ‘nosei b’oil im chaveroy’ (carrying the yoke together with a friend), this week we also shout out Jonathan Grossman, the Oisvorfer’s very own son, who today mamish, was a donor of stem cells to a 47 year old woman suffering from leukemia. Of course, Jonathan does not know the identity of this person but is now connected to her and wishes her, as do we all, a full and speedy recovery.

Just two months back Jonathan happily and very excitedly shared the news that he had received a call from the very dedicated people over at Gift of Life informing him that he was a potential match for either bone marrow or stem cells needed by a patient, and was asked if he was still interested in being further tested. He was. A few weeks later, he was advised that he was indeed a stem cell match for a leukemia suffering patient. And this past Sunday, in preparation for today’s 6 hour procedure and donation, Jonathan, not yet 23 years of age, but with great maturity and determination to do this mitzvah, began receiving daily injections. Earlier today, on Lag Bo’oimer, a day when we (many of us) ‘resume normal’, suspend, or end, the mourning period for Rebbe Akiva’s students, who according to many a medrish passed away for not taking care of one another, our son spent his time trying to help take care of a stranger. Go Jonathan!

Just two months back Jonathan happily and very excitedly shared the news that he had received a call from the very dedicated people over at Gift of Life informing him that he was a potential match for either bone marrow or stem cells needed by a patient, and was asked if he was still interested in being further tested. He was. A few weeks later, he was advised that he was indeed a stem cell match for a leukemia suffering patient. And this past Sunday, in preparation for today’s 6 hour procedure and donation, Jonathan, not yet 23 years of age, but with great maturity and determination to do this mitzvah, began receiving daily injections. Earlier today, on Lag Bo’oimer, a day when we (many of us) ‘resume normal’, suspend, or end, the mourning period for Rebbe Akiva’s students, who according to many a medrish passed away for not taking care of one another, our son spent his time trying to help take care of a stranger. Go Jonathan!

His donation was facilitated by an amazing organization known as Gift of Life (giftoflife.org) whose mission it is to cure blood cancer through marrow and or stem cell donations. It matches the blood of healthy donors to those in need. Several years back the Oisvorfer and eishes chayil signed up with Gift of Life but we had no idea that our children did as well. Chazak!

Welcome to parshas Behar, the penultimate parsha in sefer Vayikra. Very shortly, but not before we get to listen to a series of very frightening admonitions and curses the RBSO will threaten us with (next week’s parsha) -mamish enough to crawl under your covers and ask for mommy- we will begin sefer Bamidbar (Book of Numbers) where we will be following the Yiddin and their travails as they trek through the midbar (desert) for 40 years before most of them (males only) will die or be killed by the RBSO for insubordination and worse. Stay tuned.

There is lots to discuss in this week’s rather short (57 pisukim) parsha, read alone this year without its sister parsha of Bichukoiseye which many of you will not want to hear anyway. The first 24 pisukim deal with the holy concepts of Shmittah and Yoivel (jubilee) and the myriad and difficult to chap laws pertaining to them. We have previously written about Shmittah and Yoivel and you can find these gems over in archives at www.oisvorfer.com. The bottom line: Shmittah, which comes around every seven years is a magical concept. All Jewish slaves are to be freed, the land lies fallow, no farming allowed, yet its produce which is not be harvested, belongs to everyone. How all that works is beyond this short review but rest assured it is not without its controversies. What isn’t? Efsher you’re wondering how farmers are to eat, survive and support their families during the Shmittah year? Not to worry: the RBSO makes arrangements so that the farmer has enough to eat in years seven and eight. Shoin: is there any reason to question the RBSO’s abilities? Did He not deliver Mun to His Chosen People for 40 years? During Yoivel, land ownership is somehow nullified, and there are a few other festivities. Seemingly, the heylige Toirah was the first to introduce the concept of the land lease. The bottom line: all the land in Israel belongs to Him. Do we observe Shmittah in our times? Yes and no. Biblically it’s not longer relevant ober according to our rabbis, Shmittah is alive and well. Today’s farmers have of course found interesting ways to survive during the Shmittah year. One of the more recent and innovative ideas involves us Yiddin living abroad to somehow buy into their land by sending them money. In return, they give us some sham paperwork which is meant to convey ownership. Shoin, the farmer is no longer the boss, he is but an employee. He now works for us and since we live abroad and are not subject to the laws of Shmittah which is only alive and well in Israel, life is good.

And before we move on to the mitzvis of helping fellow Jews in need, let’s quickly review a most interesting thought on Shmittah. Believe it or not, Shmittah may somehow be connected to circumcision. It’s what? How can a bris which entails a shtikel cutting, snipping and pruning be in any way related to Shmittah? Shoin, leave it up to the Zoihar, he the great and holy kabbalist with no end to his imagination, to connect the dots. Says he (on the beginning of this week’s parsha) azoy: Rebbe Elozor said that every Yid that has undergone circumcision (that would taka be every Jewish male), has within him the rest of Shmittah, whatever that means. Taka, what does that mean? Ver Veyst, ober that’s what he says. Let’s avada recall that this is kabolo (mysticism) and who says you need to understand what the heylige Zoihar was thinking and said over in the name of Rebbe Elozor? One day, when you are on his level, you will chap. Shoin, case closed. The bottom line: someplace inside of you -don’t ask where- those who are circumcised, have the rest associated with Shmittah inside of yourselves. Ober what does that? Seemingly the Shmittah belongs to those circumcised and this is referred to as ‘shabbos ha’oretz’ (the resting of the land). Is it clear now? Not! Let’s try again: just as shabbis entails total rest, so too Shmittah refers to the resting of all land. Ober what’s taka pshat that a person who has undergone a bris is considered to be at rest? Have any of you oisvorfs been resting? Or, are you out there daily trying to plow, sew, seed and reap, if you chap? Ober says the RambaM (Moireh Nivuchim 3:49) azoy: one of the reasons the RBSO ordered that we undergo circumcision, was to weaken our physical desires, if you chap. Ok, that part did not work out as planned. Back to the RambaM: When one has weakened desires, he, by extension, has an increase in his emunah (faith and trust) in the RBSO who is mamish the only real true source of strength. Similarly, when the farmer allows his land to remain fallow during year seven (this is the mitzvah of Shmittah observance), and by extension has nothing to harvest in year eight, one shows greater belief and reliance on the RBSO who is the master of all and provider of all sustenance. Shoin, bris mila (circumcision and Shmittah are related. Veyter.

And before we move on to the mitzvis of helping fellow Jews in need, let’s quickly review a most interesting thought on Shmittah. Believe it or not, Shmittah may somehow be connected to circumcision. It’s what? How can a bris which entails a shtikel cutting, snipping and pruning be in any way related to Shmittah? Shoin, leave it up to the Zoihar, he the great and holy kabbalist with no end to his imagination, to connect the dots. Says he (on the beginning of this week’s parsha) azoy: Rebbe Elozor said that every Yid that has undergone circumcision (that would taka be every Jewish male), has within him the rest of Shmittah, whatever that means. Taka, what does that mean? Ver Veyst, ober that’s what he says. Let’s avada recall that this is kabolo (mysticism) and who says you need to understand what the heylige Zoihar was thinking and said over in the name of Rebbe Elozor? One day, when you are on his level, you will chap. Shoin, case closed. The bottom line: someplace inside of you -don’t ask where- those who are circumcised, have the rest associated with Shmittah inside of yourselves. Ober what does that? Seemingly the Shmittah belongs to those circumcised and this is referred to as ‘shabbos ha’oretz’ (the resting of the land). Is it clear now? Not! Let’s try again: just as shabbis entails total rest, so too Shmittah refers to the resting of all land. Ober what’s taka pshat that a person who has undergone a bris is considered to be at rest? Have any of you oisvorfs been resting? Or, are you out there daily trying to plow, sew, seed and reap, if you chap? Ober says the RambaM (Moireh Nivuchim 3:49) azoy: one of the reasons the RBSO ordered that we undergo circumcision, was to weaken our physical desires, if you chap. Ok, that part did not work out as planned. Back to the RambaM: When one has weakened desires, he, by extension, has an increase in his emunah (faith and trust) in the RBSO who is mamish the only real true source of strength. Similarly, when the farmer allows his land to remain fallow during year seven (this is the mitzvah of Shmittah observance), and by extension has nothing to harvest in year eight, one shows greater belief and reliance on the RBSO who is the master of all and provider of all sustenance. Shoin, bris mila (circumcision and Shmittah are related. Veyter.

Said the Maharal azoy: circumcision is deemed to be sustaining. And davka because of its intended side effects, Yoisef the viceroy of Mitzrayim, insisted during the famine, that all of Paroy’s subjects, undergo circumcision before he would sell them provisions. Seemingly he was hoping that with circumcision, their desires for physical pleasure would be greatly diminished, and as a result, the Mitzrim would find trust in the RBSO instead of the myriad idols they were worshipping. The circumcisions took place ober the Mitzrim continued to have desires. Of course they did and so do we all. Another well intended but failed experiment. Desires are seemingly stronger than the intended consequences of the bris.

Let’s go veyter and skip ahead to posik 25 where the heylige Toirah lays out a set of mitzvis that involve our obligations to help out a fellow Jew, including converts, and even goyim (non Jews) that have undertaken to abandon idol worship and eating non kosher meat. Though the examples provided on the type of people we must help, specifically Jewish slaves, are no longer relevant, the lessons we are taught about charity, and how it is to be dispensed, are invaluable. And why are we skipping ahead? Because this is our sixth time -can you believe it- around this parsha and we have previously covered gishmake pearls of wisdom, along with appropriate, and at times not, with abundant doses of humor and sarcasm.

We avada warned you that Shmittah includes yet another category known as ‘shmittas kisofim’ which basically wipes out any loan you may have, in good faith, extended to a friend in need. In other words: though you were a good guy and mamish wanted to, and taka did, help out another Yid in need, if his loan is not repaid before Shmittah arrives, you are out of luck. Fartig! And instead of the borrower having to spin tall tales about ‘the check being in the mail’ or ‘I’ll pay you tomorrow or next week’, and then giving you a series of checks that bounce higher than did your Spalding or Pensy-pinky balls you played with back in yeshiva, the borrow can dispense with you and your loan by uttering but one word: Shmittah! Your loan is nullified, dead mamish. As an aside, the few examples of excuses for not having your loan repaid are not meant to limit in any way the creativity of the borrowers not to repay. Those are endless. Who says that just because you were kind enough to help a person in his time of need that you deserve repayment? Moreover, according to many (especially those who are frequent borrowers), your asking for your monies which you nebech counted on and efsher now need, in a Shmitah year, is an aveyro (sin) mamish. Yikes!

We avada warned you that Shmittah includes yet another category known as ‘shmittas kisofim’ which basically wipes out any loan you may have, in good faith, extended to a friend in need. In other words: though you were a good guy and mamish wanted to, and taka did, help out another Yid in need, if his loan is not repaid before Shmittah arrives, you are out of luck. Fartig! And instead of the borrower having to spin tall tales about ‘the check being in the mail’ or ‘I’ll pay you tomorrow or next week’, and then giving you a series of checks that bounce higher than did your Spalding or Pensy-pinky balls you played with back in yeshiva, the borrow can dispense with you and your loan by uttering but one word: Shmittah! Your loan is nullified, dead mamish. As an aside, the few examples of excuses for not having your loan repaid are not meant to limit in any way the creativity of the borrowers not to repay. Those are endless. Who says that just because you were kind enough to help a person in his time of need that you deserve repayment? Moreover, according to many (especially those who are frequent borrowers), your asking for your monies which you nebech counted on and efsher now need, in a Shmitah year, is an aveyro (sin) mamish. Yikes!

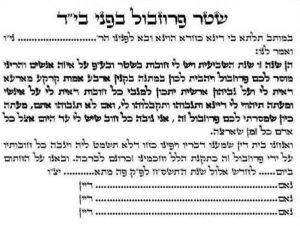

We also told you how this was rectified when lenders, as a result of not being repaid and having their loans nullified, stopped lending to those in need. What taka happened? Shoin, leave it up to our enterprising sages and along came a fellow known as Hillel Hazokan (Hillel the elder) who chapped that this situation was intolerable mamish and was having a deleterious effect on the Yiddishe underground economy of money lending. Moreover, if the lenders weren’t being repaid, their cash flow was adversely affected and as a result they had fewer, or no dollars left over with which to support their local rabbis. Donations to the rabbis during the sale of chometz, on Purim, and efsher for making a guest appearance at a wedding, were dwindling mamish. The rabbis immediately recognized that drastic measures were being called for. It’s one thing for a lender not to help out his less fortunate chaver, ober, when the side effects of the Yiddin not repaying their loans meant that the rabbis pockets and their own free cash flow was suffering, they sprang into action.

What to do? They introduced us to one of the greatest loopholes ever, this one known as the Pruzbil. What the hec is a Pruzbil and how does it work to a lender’s advantage so that his good deed of lending monies out to other needy Yiddin – without interest which is of strictly verboten- as this parsha and as we will learn again in Sefer Devorim (Ki Say Tzey) will teach us? In short it works azoy: the lender assigns his receivable to the community rabbis. Shoin, he is no longer the lender. Next: the rabbis (hiding behind their communal coffers) are allowed to collect the debt from the borrower. The rabbis avada charge or expect a healthy vig for their participation and life is good. For those that were not yet dedicated oisvorfer followers in previous years where we delved bi’a’richus into these loft concepts, avada you should visit archives at www.oisvorfer.com. Veyter.

Speaking of loans…lommer lernin (let’s learn) two key pisukim that deal with helping others and how. Says the heylige Toirah (Vayikro 25:35-36) azoy: “If your brother become impoverished and his means falter in your proximity, you shall strengthen him -proselyte or resident- so that he can live with you. Do not take interest and increase, and you shall fear your God- and let your brother live with you.” Shoin, efsher the RBSO was concerned: were He to allow lenders to charge interest and were the borrowers to ultimately default, might the lives of borrowers be in jeopardy? Ver veyst?

Speaking of loans…lommer lernin (let’s learn) two key pisukim that deal with helping others and how. Says the heylige Toirah (Vayikro 25:35-36) azoy: “If your brother become impoverished and his means falter in your proximity, you shall strengthen him -proselyte or resident- so that he can live with you. Do not take interest and increase, and you shall fear your God- and let your brother live with you.” Shoin, efsher the RBSO was concerned: were He to allow lenders to charge interest and were the borrowers to ultimately default, might the lives of borrowers be in jeopardy? Ver veyst?

Let’s look at the last words again: ..’and let your brother live with you.’ The very posik which instructs us not to charge interest on loans made to a fellow Jew, concludes with the words ‘V’chay ohchico imoch’ (and let your brother live with you). Grada the Oisvorfer once heard a gishmake pshat on these words, one that you can say over at the shabbis tish and one that will make you look like a shtikel ben-toirah though you are mistama not. What is the connection between these three (in Hebrew) words and the prohibition against charging interest on loans? Will your brother live with you only and davka because you are not charging interest? Ober says the heylige Gemora (don’t recall which one or where) azoy: one who lends money on interest, will not stand up at the time of ‘tichiyas hamaysim’ (resurrection of the dead). For the Oisvorfer’s not (yet) religious or Jewish readers, let’s explain. We are taught (to believe) that upon the arrival of the Moshiach, all the dead will come to life. How this might manifest requires lots of faith and a healthy dose of imagination. Ober, let’s say it’s taka so. Says the heylige Gemora: one who has the temerity to charge interest on loans though mamish so prohibited, will not be zoiche (merit) to be resurrected. Moreover, this extends as well to the borrower who has accepted the interest payments upon himself. Why? Because he has enabled the lender to violate this prohibition. And now the words taka make sense. One should not charge interest on extended loans, and if one does not, both you and your brother(in this case the borrower) will ‘live’ and get to witness tichiyas hamaysim. Mamish gishmak. Veyter.

Let’s close with posik 35 quoted mamish above which exhorts us to strengthen or grab onto our brothers’ (not meant literally) that are becoming impoverished. The two key words in the verse are ‘Vihechezakto Boi (you shall strengthen). Mistama you have heard these words before and many commentators believe azoy: the specific wording is meant to teach us that we must extend a hand (in the form of money or other help) to a friend and even stranger who is faltering. He is not yet totally poor, he has yet to be evicted from his house. He may still have a few shekels with which to buy gas for his car and keep the lights on. Says the RambaM azoy: there are eight different levels of giving charity and the highest form of them all entails the giving to a person in need in such a way where he will not continually be reliant on charity. He will, through your help, become independent. In other words: if he loses his job, perhaps you can employ him or help him get employment. If he lost his business, perhaps you can help get into a new venture. The examples are many. And his basis for elevating this form of charity above others, are the two words of “vehechazakto boi.” And says the Beis Yoisef so gishmak azoy: this form of charity ranks highest because it allows the recipient to accept help without embarrassment. He does not see himself as being the recipient of handout. He can retain his dignity.

Let’s close with posik 35 quoted mamish above which exhorts us to strengthen or grab onto our brothers’ (not meant literally) that are becoming impoverished. The two key words in the verse are ‘Vihechezakto Boi (you shall strengthen). Mistama you have heard these words before and many commentators believe azoy: the specific wording is meant to teach us that we must extend a hand (in the form of money or other help) to a friend and even stranger who is faltering. He is not yet totally poor, he has yet to be evicted from his house. He may still have a few shekels with which to buy gas for his car and keep the lights on. Says the RambaM azoy: there are eight different levels of giving charity and the highest form of them all entails the giving to a person in need in such a way where he will not continually be reliant on charity. He will, through your help, become independent. In other words: if he loses his job, perhaps you can employ him or help him get employment. If he lost his business, perhaps you can help get into a new venture. The examples are many. And his basis for elevating this form of charity above others, are the two words of “vehechazakto boi.” And says the Beis Yoisef so gishmak azoy: this form of charity ranks highest because it allows the recipient to accept help without embarrassment. He does not see himself as being the recipient of handout. He can retain his dignity.

Says the heylige Gemora (Pisochim 8a) azoy: if a person states, “I will give this coin to charity so that my son will live,” -meaning that his donation is specifically tied to the recovery of his child- such a man is ‘tzadik gomur (totally righteous and pious individual). Ober how can it be that a person who gives conditional charity is deserving of this appellation? Not just is he considered a tzadik, an appellation reserved for a few, but a totally pure and righteous individual?! What’s’ taka pshat? Ober one should never doubt the wisdom of the heylige Gemora who chapped that the case at bar is referring to an individual who is giving charity but wants to ensure that the recipient will not be shamed by accepting the charity. He therefore states that he, the donor, is the real beneficiary of the charity. Because he has a sick son and because the recipient, as a result of the condition placed may have a hand in helping the RBSO cure his child, he, the recipient of the charity, may have helped the donor. It’s role reversal. And says the Gemora azoy: he who devises a plan or method of giving charity while avoiding humiliation to the recipient, is considered a tzadik gomur. Gishmak.

By extension, this concept surely applies to any type of charity or kindness extended. The highest level of kindness involves making sure the recipient is not made to feel embarrassed in any way, shape, or form. Grada the Oisvorfer was thinking about this concept mamish today as his son Jonathan was sitting for six hours and donating stem cells anonymously. Organizations and individuals dedicated to helping others and that do so with total anonymity, are mamish to be lauded.

By extension, this concept surely applies to any type of charity or kindness extended. The highest level of kindness involves making sure the recipient is not made to feel embarrassed in any way, shape, or form. Grada the Oisvorfer was thinking about this concept mamish today as his son Jonathan was sitting for six hours and donating stem cells anonymously. Organizations and individuals dedicated to helping others and that do so with total anonymity, are mamish to be lauded.

A gittin Shabbis-

The Oisvorfer Ruv

Yitz Grossman