Raboyseyee and Ladies,

Before we begin, you must read this very critical and timely article penned by Rabbi Benjamin Blech:

https://blogs.timesofisrael.com/when-history-rhymes/

When history rhymes

NOV 30, 2023, 8:21 AM

Mark Twain profoundly observed that “history never repeats itself, but it does often rhyme.”

Today’s Middle East conflict between Israel and Hamas goes back years. It is a battle that seems to have no end. And the war not only rages between the direct two participants but also with millions of observers as well.

After the barbaric savagery of October 7, as Hamas ignored an existing ceasefire and committed atrocities against Jews not seen since the Holocaust, we rationally would have assumed that the world would condemn the perpetrators of unimaginable evil. However, as we all have come to sadly recognize, the victims have somehow become the villains, while, amazingly, the initiators of violence have for many been granted the greater claim to moral support.

Shades of a remarkable biblical story. In fact nothing less than an echo of the very first murder in history.

It is the Bible that records the event. Even before there were nations, fratricide took place in a family. Cain murdered his brother Abel. The context mystifies many readers.

Here are the words in Genesis 4:8: “And Cain said to Abel his brother. And it came to pass, when they were in the field that Cain rose up against Abel his brother and slew him.” The verse begins by informing us that Cain said something to Abel – yet never tells us what he said! The murder is shrouded in mystery. All we know is that “Cain said to Abel his brother”!

Jewish commentators provide us with a remarkable — and currently relevant — answer. The missing words are in fact provided in the text. They explain Cain’s “success” in accomplishing the killing of Abel: “Cain said to Abel ‘his brother.’”

Cain was wise enough to grasp Abel’s chief weakness. Abel may have been physically stronger, but he had a conscience. What Cain could not resist was a plea to Abel’s ethical principles, to his commitment to family and brotherly love. So Cain shrewdly stressed that he was after all still “his brother.”

Abel acceded to Cain’s humanitarian plea — and signed his own death warrant.

It is time to relearn the biblical truth that there is a time for peace and a time for war. To ignore the reality that Hamas itself proclaims — its goal the continued murder of Israelis and Jews as well as an end to the civilized Western world — is to echo Abel and choose suicide “on humanitarian grounds.”

“Humanitarian grounds” has such a nice ring to it. It almost sounds biblical. So, in one of the most unbalanced hostage trades in history, Israel some years ago, in 2011, released over 1,000 Palestinian prisoners, many with blood on their hands, in exchange for one captive soldier Gilad Shalit.

When finally Shalit returned to Israel, some 1,027 Palestinian prisoners were set free, amid sharp criticism in Israel. Among the freed prisoners were killers sentenced to life in prison and masterminds of attacks against Israelis. A Hamas military leader, Ahmed Jabari, was quoted in the pan-Arab newspaper Al-Hayat as confirming that the prisoners released under the deal were collectively responsible for the killing of 569 Israelis. In the years that followed many more horrific murders were the work of those freed in the name of a “humanitarian purpose.”

Perhaps the most ironic result of Israel’s display of “brotherhood” was the tragedy of the recent massacre of October 7 — orchestrated and planned by Yahya Sinwar, the current leader of Hamas in Gaza, who was one of the prisoners released in the Shalit exchange, after his four life sentences were cut short by the deal.

Should we not have learned the lesson of Cain that there are times when murders need to be prevented by resistance to duplicitous pleas ostensibly made in the name of righteousness? When Cain called for a cease fire because he was losing the battle, Abel let down his guard — and lost his life.

The Talmud at first called the payments for release of hostages a major mitzvah. But when enemies of the Jews realized that they possessed a “golden egg” for endless wealth by taking hostages for whom huge sums of ransom would be paid — a humanitarian trait responsible for the very opposite result so that taking prisoners greatly escalated — the rabbis called a halt to the newly created gentile “business.” When the great German talmudist and poet Rabbi Meir of Rotenberg, one of the shining lights of 13th-century Jewry, was kidnapped and held for an exorbitant ransom, he famously directed his community not to pay and he died in prison after seven years of captivity.

With heavy heart and much soul searching I wonder if we too have an obligation not to heed the seemingly seductive and humanitarian claim of Cain to embrace our mutual “brotherhood” — when our “brother” makes it clear that massacre remains his objective and our death is the only end that will satisfy his hatred.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Rabbi Benjamin Blech is a Professor of Talmud at Yeshiva University and an internationally recognized educator, religious leader, and lecturer.

———————————————————————————————————————

Name Changes & Changing One’s Luck

Let’s start here. This past Friday night, the heylige Ois got into a long discussion with one of his machatunim about Eisav: was he or was not he a bad guy? Neither of us could be persuaded and here we are one parsha later; Parshas Vayishlach may help us resolve the matter. As it’s my thing to learn the parsha somewhat backwards, I was mamish awestruck again- to find that the RBSO dedicated 43 -yes that number is correct- 43 pisukim at the end of the parsha to everyone’s favorite villain, Eisav. Well blow me down! And guess what? Not one bad word is mentioned. Typically, when the RBSO does not like someone -by way of example Eyr and Oinon about whom we will be reading next week- they appear and disappear in a flash. They appear in less than a handful of pisukim. Some villains hang around, but none get 43 consecutive pisukim dedicated to their progeny and family tree. Mamish like a yichus breef (pedigree letter) to show off. Yet Eisav gets a full 43 plus so much more coverage; what’s pshat?

Why taka does the heylige Toirah list his entire family? What is the significance? Let’s check this out from the late and great Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz who says that the digression here to recount Eisav’s progeny is to highlight the fulfillment of the blessings he received from his father Yitzchok. Though Yaakov did -through trickery- end up with the birthright and blessings that came with it, and though it may have well been what the RBSO had in mind from the get-go, Yitzchok loved Eisav and still had some in his tank to dole out. Eisav got those. All of Eisav’s many descendants came to rule over specific lands; not too shabby.

Another pshat: Eisav’s family tree is davka listed here just as Yishmoel’s generations were following Avrohom’s death (this perek appears after Yitzchak’s death). Once the heylige Toirah “narrative” is essentially finished with a main actor, there’s a resultant summary of the legacy. Eisav is not directly mentioned anymore following this episode.

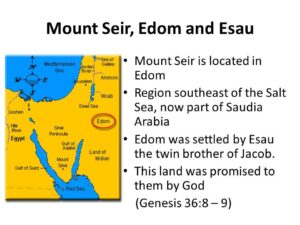

Ober, the heylige Ois reminds his readers of this factoid, one not to be forgotten: The RBSO Himself gave Eisav certain blessings and lots of land. In Sefer Devorim (2:4-5) we will be reading this:

אַתֶּ֣ם עֹֽבְרִ֗ים בִּגְבוּל֙ אֲחֵיכֶ֣ם בְּנֵי־עֵשָׂ֔ו הַיֹּשְׁבִ֖ים בְּשֵׂעִ֑יר וְיִֽירְא֣וּ מִכֶּ֔ם וְנִשְׁמַרְתֶּ֖ם מְאֹֽד׃ (ה) אַל־תִּתְגָּר֣וּ בָ֔ם כִּ֠י לֹֽא־אֶתֵּ֤ן לָכֶם֙ מֵֽאַרְצָ֔ם עַ֖ד מִדְרַ֣ךְ כַּף־רָ֑גֶל כִּֽי־יְרֻשָּׁ֣ה לְעֵשָׂ֔ו נָתַ֖תִּי אֶת־הַ֥ר שֵׂעִֽיר׃

“You will be passing through the territory of your kinsmen, the descendants of Eisav, who live in Seir. Though they will be afraid of you, be very careful (5) not to provoke them. For I will not give you of their land so much as a foot can tread on; I have given the hill country of Seir as a possession to Eisav.

The bottom line: Eisav was zicher hated –as we have mentioned in past weeks and years- by Rashi and many a midrash, ober by the RBSO? Not so sure. Case closed! Let’s move on to another gevaldige topic.

Welcome to Parshas Vayishlach which features lots more action and yet another -seemingly significant- name change. What’s pshat another? For reasons only the RBSO knows, in our parsha, He decided to change Yaakov’s name to Yisroel. More on that below, ober, is Yaakov to Yisroel the first name change we have encountered in the heylige Toirah? Not! The first in Sefer Bereishis? Also not! What’s up with all the name changes? Who else underwent a name change? Why? Did the new name always stick? Throughout the heylige Toirah and in Tanach –more prevalent in Bereishis and Shmois- various people have their names changed. Avrom became Avrohom, Sorai was changed to Soro and in Sefer Shmois, Ho’shay’a to Yehoshua. There’s more: Says the medrish that Yisroy (Jethro), Moishe’s father-in-law, was originally named Yeser but when he “added” good deeds (to himself), a letter (vav) was added to his name. What happened to those who did bad deeds? In the Novee, we will read about Yehonadav who became Yonadav after advising Amnon how to sin with Tamar. He lost the letter yud. Read all about that in (II Divrey Hayomim 20:37). Let’s not forget Shifra and Puah, the meritorious midwives who saved the Jewish babies in Egypt. They had their names changed to Yoicheved and Miriam. Hadassah changed her name to Esther (hidden), perhaps, as the name implies, to hide her true identity as being of the Jewish faith. As an aside, here were in 2023 and some are doing the same; oy vey. Another pshat: to hide her true virtue as Hadas (myrtle) which is a symbol of righteousness (Zechariah 1:8).

At times, name changes were made by non-Jews, as in the case of Yoisef’s name being changed to Tzofnas Paneyach (Bereishis 41:45) by King Paroy. Nebuchadnezzar’s chief officer changed Daniel’s name to Belteshazzar as a reference to a pagan god. And now you know.

In our parsha, Yaakov’s name is changed twice. When Yaakov returns -after twenty years-from living with Lovon, he encounters an angel -seemingly in disguise as a human- on the way and wrestles with him. Later in the parsha, the RBSO will also change his name. Both times his new name is Yisroel. He is morphed twice from the ‘one who grasps ankles’ to ‘the one who wrestles with G-d.’ The first time he is renamed by some unnamed adversary he wrestles with throughout the night (32:29). In that story, Yaakov asks for a brocho before releasing the angel, whom he had just defeated. The angel responds:

בראשית לב:כח וַיֹּאמֶר אֵלָיו מַה שְּׁמֶךָ וַיֹּאמֶר יַעֲקֹב.לב:כט וַיֹּאמֶר לֹא יַעֲקֹב יֵאָמֵר עוֹד שִׁמְךָ כִּי אִם יִשְׂרָאֵל כִּי שָׂרִיתָ עִם אֱלֹהִים וְעִם אֲנָשִׁים וַתּוּכָל.

Gen 32:28 Said the other, “What is your name?” He replied, “Yaakov.” 32:29 Said he, “Your name shall no longer be Yaakov, but Yisroel, for you have striven with beings divine and human, and have prevailed.”

A little later on, when Yaakov arrives in Bethel, he is again named Israel, this time by the RBSO.

בראשית לה:ט וַיֵּרָא אֱלֹהִים אֶל יַעֲקֹב עוֹד בְּבֹאוֹ מִפַּדַּן אֲרָם וַיְבָרֶךְ אֹתוֹ. לה:יוַיֹּאמֶר לוֹ אֱלֹהִים שִׁמְךָ יַעֲקֹב לֹא יִקָּרֵא שִׁמְךָ עוֹד יַעֲקֹב כִּי אִם יִשְׂרָאֵל יִהְיֶה שְׁמֶךָ וַיִּקְרָא אֶת שְׁמוֹ יִשְׂרָאֵל.

Gen 35:9 G-d appeared again to Yaakov on his arrival from Paddan-aram, and He blessed him. 35:10 G-d said to him, “You whose name is Yaakov, you shall be called Yaakov no more, but Israel shall be your name.” Thus He named him Israel.

Interestingly, this posik makes no reference to the previous renaming, mamish ignores what the malach had previously told Yaakov. Did the malach have permission for the renaming? Other questions on your mind may include these: why is his name change presented to us twice? And why taka doesn’t it stick? Moreover, doesn’t the RBSO Himself calls him Yaakov when he appears to him in a dream in Egypt (Bereishis 46:2)? He does. And doesn’t Yaakov enthusiastically respond, “Here I am?” He does! And don’t we Yiddin -in today’s times mirror the RBSO’s preference when davening thrice daily by referring to “the G-d of Avrohom, Yitzchok and Yaakov rather than the “G- d of Israel?” We do. What’s pshat with this name change? Was it for legal reasons only? Had Yaakov declared bankruptcy after being chased down by Elifaz and stripped of all his possessions -and according to some, even of his clothing, say it’s not so?

And when reciting Tehilim (Psalms) do we not come across this posik (53:7) “When Hashem restores the fortunes of His people, Yaakov will exult, Yisrael will rejoice?” We do! What’s happening with this name change? Was it an added name versus a name change? More on that possibility below.

Nu, efsher we can kler azoy: the first time around the unnamed person or angel merely predicted that in the future his name would be changed. And taka, later on, the RBSO confirmed the name change. Says the Ramban (35:10) so gishmak azoy: before assigning Yaakov his new name, the RBSO states plainly “your name is Yaakov,” since it wasn’t the angel’s mission to change Yaakov’s name. Was the angel not just out of place but also out of line? Says R’ Shamson Refoel Hirsch (on 32:29) also so gishmak azoy: there is a difference between the verbs in the two pisukim. The angel says “לא יעקב יאמר עוד שמך”, which R’ Hirsch interprets as “not Yaakov shall they name be expressed any more,” while the RBSO says “לא יקרא שמך עוד יעקב”, which R’ Hirsch interprets as “thy name shall no longer be called Yaakov.” In other words, the emphasis is on the wrong syllable and shoin. According to R’ Hirsch, the angel’s message was not that Yaakov’s name was changing, but that the same name Yaakov would now be understood as Yisroel, meaning “G-d is the All-conquering one.” When people see a “Yaakov” apparently a weak member of the “heel” of society, miraculously overpowering stronger-looking foes, it demonstrates that the RBSO is all-powerful, and that He can and does intervene to help those who are close to him vanquish any power. When this happens, “Yaakov” teaches the world that “Yisroel” is in charge. Shoin, all reconciled, ober Is that pshat? Let’s see another.

Our sages tell us that Yaakov’s name change was unique in several respects. Ershtens, his name was changed entirely and not simply altered by the addition or subtraction of a single letter. Its meaning changed from referring to his grasping of Eisav’s heel (ekev) to meaning, “one who has struggled with man and G-d and has prevailed.” Yaakov’s name change is also different from that of Avrohom who is never referred to as Avrom afterward. Says the heylige Gemora (Broches 13) that anyone who calls Avrohom by his previous name, ‘Avrom,’ violates a mitzvas ah-say (positive commandment); it’s halachically proscribed since the RBSO specified, “And your name will be Avrohom” (Bereishis 17:5). Ober, as we shall see below, Yaakov’s name change – though changed not once, but twice- wasn’t very sticky. It was more reminiscent of a post-it- note. Farkert: the heylige Toirah refers to him many times as Yaakov after the angel and then the RBSO Himself renamed him. What’s pshat? If other name changes stuck, why didn’t Yaakov’s new name? Why taka was he still called Yaakov when the malach stated rather explicitly, “Your name shall no longer be Yaakov, but Yisrael?” And why wasn’t Avrom ever used again?

Say the Baaley Hatoisfis that Avrohom’s name changed as he underwent a metamorphosis. The new name was given at the juncture at which most Jewish males are given their name – at the bris ceremony when they are circumcised. Precisely because the new name was part of his conversion, the old identity -and a few centimeters -or more- off the bottom, if u chap, was forfeited. Ober Yaakov, unlike Avrohom, was born “Jewish”, was circumcised on the eighth day after his birth and given his name concurrently. Accordingly, his new name must have a different purpose.

All that being said, the problem of the persistence of the name Yaakov after two renamings has bothered our sages of yore, one approach -mentioned above-was to suggest that Yisroel was not meant to replace Yaakov, but to supplement it. And taka, says the Ibn Ezra (35:10), azoy:

לא יקרא שמך עוד יעקב לבדו כי גם ישראל.

Henceforth, you shall not be called Yaakov exclusively, but also Yisroel. Seemingly, his first name was established for him by his mother and the second added for him.

The medrish (Bereishis Rabbah (78) actually records a debate about the exact the relationship between these two names:

תני לא שיעקר שם יעקב אלא כי אם ישראל יהיה שמך, ישראל יהיה עיקר ויעקב טפילה.

It was taught: It isn’t that the name Jacob was to be uprooted, “rather Yisroel will be your name” – Israel will be the main [name] and Yaakov will be secondary.

ר’ זכריה בשם ר’ אחא מכל מקום יעקב שמך אלא כי אם ישראל יהיה שמך, יעקב עיקר וישראל מוסיף עליו.

R. Zechariah in the name of R. Acha said: “Yaakov is certainly your name, “rather Israel will be your name” – Yaakov is your main name and Yisroel is added to it. Shoin and now you know, ober while this pshat is mamish creative -as medrish kimat always is- it certainly does not comport with what the text of the heylige Toirah says: The pisukim (32 and 35) never say or imply that Yisroel is an extra name; they both state clearly that the name Yaakov is replaced by Yisroel.

Not to worry because says Rashi mamish so cleverly azoy:

לא יעקב יאמר עוד שמך – לא יאמרו עליך עוד שהברכות בעקיבה וברמייה כי אם בשררה ובגילוי פנים, סופך שהקב״ה נגלה עליך בבית אל ומחליף את שמך ושם הוא מברכך

“Your name shall no longer be Yaakov” – people will no longer say about you that you received the brochis through trickery and deceit (the meaning of “Jacob”), but rather with striving and openly (the meaning of “Yisroel”), and in the end, the RBSO will appear to you in Bethel and change your name and there he will bless you. Rashi’s pshat is that the name Yaakov indicates subservience, while the name Yisroel indicates strength and victory. Varying uses reflect different aspects of Yaakov’s personality that came to light in varying situations. At times, he was Yaakov, at others, he was Yisroel.

The bottom line: We can kler -as do others- that Yaakov’s name was not changed; rather, he received an additional name. And says the Meshech Chochma azoy: the different names express the distinction between Yaakov as an individual versus Yisroel as a national identity. In his view, the RBSO addresses “Yisroel” exclusively when, and only when, there are national issues at hand. And says the Netziv that the distinction is between a supernatural aspect (Yisroel), versus a more mundane name (Yaakov) used when natural events or actions are described. Because humans cannot function purely on the spiritual plane, both names were needed. Exactly what that means, ver veyst?

The bottom line: Each of these suggestions seems to point to an unresolved tension in Yaakov’s life which results in a dual identity. The heylige Gemora (Brochis 12b-13a) notes the same and concludes that Yaakov did not have his name changed as did Avrohom and Soro. Rather, he was given an additional name.

Shoin, since we’re talking about name changes, it’s mamish kiday (worth our time) to find out what the heylige Gemora has to say about names changes. Why are names changed? Says the heylige Gemora that the name given to a child affects his future [Broches 3b-4a]. in fact, Jewish law requires that one be extremely careful in spelling out people’s names on official documents. The documents are void if the name is written incorrectly. And this: The Gemora (Rosh Hashona 16b) also tells us that one of four ways to avoid something bad happening to you is to change your name. This shtikel Gemora gave rise to the minhag (custom) of changing the name of a very sick person. Why? To fool the Malach Hamoves (Angel of Death). Seemingly his marching orders contain a very specific name; change it and he cannot find you! Givaldig! Of course it helps knowing that he’s targeting it or on his way.

There’s more good stuff in the heylige Gemora; isn’t there always?! The same Gemora lists four things that can cause an unfavorable decree against a person to be torn up, and one of them is a change of name. How does this work?

Says the Ran azoy: the function of a name change is to inspire a person to do Teshuva (repentance). The name change helps concretize the idea that henceforth the person must act differently, and that he no longer is the same person as the one who previously committed improper deeds. Do all agree? Of course not and says the Maharsho that it’s not emes: the name change is not necessarily designed to inspire teshuva. And his proof? Let’s roll back to Parshas Chaya Soro where Rashi (on Bereishis 23:1) tells us what we all recall learning in yeshiva: at the age of 100 Soro was as free of sin as a 20-year-old! Therefore, we may conclude that her name change was not needed to motivate her to ‘clean herself up’ spiritually. She was a pure soul. Rather, the significance of a name change – and how it brings about a rescinding of an unfavorable decree – is to bring a change to a person’s mazel (luck). As it turns out and we all know such people, some just have too much bad luck!

What to do? Change the name! Once a name has been changed, the mazel previously associated with that name no longer applies to him/her, and this is even true when it had been decidedly unpleasant. Wow! And his proof? The heylige Toirah itself proves this point: In the posik immediately following Soro’s name change (17:18) the heylige Toirah records that she – who had been barren for almost 90 years – will now be blessed with a child: “I will bless her; indeed, I will give you a son through her.” Mamish gishmak!

A gittin Shabbis-

The Heylige Oisvorfer Ruv

Yitz Grossman