Raboyseyee and Ladies,

We begin with mazel tov wishes to our children, Ariella and Zachary Grossman upon the birth last week and the bris this past Monday of their son Yaacov Gavriel (Jack William). May he- named after the Ois’s father, OBM- be a source of continuous nachas, pride and joy to his parents, grandparents on both sides, great grandparents, uncles, aunts and cousins.

From simcha to simcha, last night we joined our friends Rachel and Avi Korngold at the very spirited wedding of their beautiful daughter Malka who was escorted down to the chuppah to marry Avi Biberfeld, son of Ilana Biberfeld and Shimon Biberfeld. May Malka and Avi merit to enjoy many decades of marital bliss. Mazel tov to both extended families. So happens that the Ois goes back many decades with the Biberfeld/Mandel family and was very much looking forward to participating in this great simcha.

The Gentile Loophole & Hydroponics

First the good news: Behar is a tiny parsha, only 57 pisukim (5th shortest) barely enough time to engage in a decent conversation with your chaver. It ranks 8th in number of mitzvis; not too shabby for a tiny parsha. Behar is the 32nd of 54 parshas and next to last in Vayikra. Ober because it’s not a leap year and efsher taka because it’s difficult to get into some juicy loshoin horo in but 57 pisukim, the rabbis added another parsha with 78 and this shabbis you’ll have a total of 135 pisukim during which you can either initiate, participate in, or add to what is being said by someone, who heard from someone, something about someone else. A few will be more machmir (strict) and will only discuss these topics bein-gavra- ligavra (between aliyos) so as not to disturb the decorum of the shul.

Moreover, it’s mistama the case that you won’t be paying much attention anyway to parts of Bichukoisai as the baal koira is required to read them in a hushed tone. Why is that? Because the parsha -as you should well remember- contains 49 different admonishments, punishments and worse, the RBSO has in store for bad behavior. That being said, our sages declared that we not really hear them clearly when being read. How that makes sense, ver veyst? Let’s get real: if someone is reading in a hushed tone, it must mean that he doesn’t want us to hear what he’s reading. Should we then annoy him by paying close attention? Mistama not! And if that weren’t enough, the curses the RBSO will lay out in the back half of our doubleheader, will mostly be repeated – in even greater detail- later on in parshas Ki Sovi. Why worry now?

With the reading of Bichukoisai, we will conclude Sefer Vayikra. Next week as we begin book number four, Sefer Bamidbar, we’ll re-visit the Yiddin as their trek through the desert, originally scheduled to take but days and weeks, will -for the sin of a few miraglim (spies) and some oversized fruit they schlepped back and then described- be elongated into 40 years. During that time period, the Yiddin, mistama bored out of their minds with little to do -no TV, cable, satellite, streaming, Instagram, and without Tic Tok to follow and memes to share, will resort to making their own entertainment. The RBSO will not be pleased with their selected activities and will take the opportunity to thin out the population so that by the time the Yiddin will make it over to the Promised Land, none of the men who had left Mitzrayim –with the exceptions of Yihoisuha, Kolave and perhaps a few unnamed others- will be alive for the final journey.

Kimat di gantze parsha of Behar (nearly the entire parsha) is dedicated to Shmita and Yoivel. Who and what are they you ask? It’s a bizoyoin (shame and disgraceful) to even hear the question and only a bum -an oisvorf- would taka dare. Shmita and Yoivel are concepts – mitzvis, heylige ones that the RBSO Himself gave over (apparently) at Har Seenai. So why repeat them here? Efsher we can kler (ponder) that the Yiddin were too mesmerized with the thunder, sound, and light show, or perhaps, they were too shocked to hear the five loi sah-says (thou shall not dos) that day. As a result, they mamish weren’t paying attention when the RBSO himself told them about the laws of Shmita and Yoivel. The bottom line: they are repeated in our parsha.

What the hec is Shemita? Literally it means a “release“ and zicher not what you are thinking, chazir that you are. It means that every farmer and land owner in the land of Israel is commanded to leave his farmland, his vineyard and orchard and stop all agricultural activity. He must refrain from plowing, seeding, reaping, fertilizing, planting, pruning and gathering both the fruit from the trees and the vegetables of the ground. Nu, for all you farmers out there, if you chap, going a year without plowing, seeding, reaping, fertilizing, planting and pruning, seems a shtikel harsh. For married farmers, going one year without, may be a shorter time period than they are used to, if you chap. Ober there is good news: Seemingly plowing and other such activities, outside the land, are quite ok, if you chap. Shemita, like the holy Shabbis, comes in cycles of sevens and like the Shabbis, certain activities are forbidden. Ober, unlike the 25 hour Shabbis -depending of course on which shul you attend- Shemita lasts an entire year.

Why did the RBSO proclaim Shemita? Ver veyst, ober some say it was to reinforce the concept that we are not the masters of our destiny. Nu, that’s no big chiddish (newsworthy); most of you have not been masters of your domain since high school, if you chap. With Shemita observance, we taka learn that the RBSO is the real owner of the world and it is He, not us, that makes the final decisions. Shoin!

We have previously covered these parshas, alone and together. You can of course find many gevaldige insights on these parshas over at www.oisvorfer.com. We’ve covered Shmita and Yoivel in depth and also discussed how some of the mitzvis found in Behar gave birth to a few of the greatest sanctioned loopholes and how the wise men of that time figured out that loopholes are an integral part of our Toirah observance. The bottom line: Bazman hazeh (in our times) we do not mark Yoivel (Jubilee) for a variety of reasons. And as to Shmita, volumes have been written and rabbis continue to argue over its observance in our times. Much ink -and spoiled fruit- continues to be spilled. And the bottom line? Aside from a shtikel plowing we -all over the world attempt from time to time, if you chap- most of us are not farmers and these laws mostly do not apply to us. Ober, what to do and how to feed the country’s burgeoning population (recently estimated at near 10 million) during a shmita year? As a reminder, Shmita laws apply only in the holy land of Israel. And the answer is azoy. Let us thank the RBSO who blessed us with a small number of Yiddin who have dedicated years to the study of the folios of the heylige Gemora and other books. These people -daring mamish- inspired by this week’s parsha which itself inspired several of the most popular kosher and still in us loopholes- came up with another brilliant idea on shmita. As a result, and in a loophole not dating back too many years -efsher a decade or a shtikel more- came up with a brilliant idea: Sell the farm! What’s pshat?

They took a page out of the Pesach playbook and decided azoy: given that our rabbis resolved that the sale of chomatze to the unsuspecting goy was kosher and allowed us to keep pour chomate in our own homes, why not do the same to avoid Shmita restrictions? Let’s try that one more time. In recent years, many farmers are able to market their produce thanks to a clever workaround (loophole); they temporarily sell their farms, valued together at billions, to some unsuspecting goy. During the off season, this same goy mistama also buys chomatze before Pesach. What is the Ois talking about? How does the temporary sale of a farm allow its real owner and many others to enjoy what was produced on the land during Shmita? The short answer and the bottom line: business is business and our rabbis -assuming that’s what the RBSO would want from us- came up with another gevaldige loophole: the sale to the goy! I love it!

Another bottom line about business: it’s taka emes, that only a minority of the Israeli population abides by strict Jewish religious law, ober, nearly all Israeli Jewish farmers choose to follow the biblical directive of Shmita observance, in part, so they don’t lose their orthodox customers’ business. Gishmak! Some farmers employ another clever solution to avoid tilling the soil: they use hydroponics, growing produce not in soil but in nutrient-enhanced water. Shmita avoidance; gishmak.

Hydroponics? What’s that? Hydroponics is the technique of growing plants using a water-based nutrient solution rather than soil, and can include an aggregate substrate, or growing media, such as vermiculite, coconut coir, or perlite. Hydroponic production systems are used by farmers, hobbyists, and commercial enterprises. Got that? And its connection to Shmita or the great shmita workaround? It’s mamish givaldig! According to the heylige Toirah, the laws of Shmita refer specifically to working the land (as in, actual soil connected to the earth). Ober, hydroponics is farming without soil and shoin! The bottom line: at least technically, this type of farming is ok even on a Shmita year. In fact, using one’s farm to grow hydroponically, is not as great a loophole around the laws of Shmita as is the Heter Mechira (symbolically selling the land to a non-Jew for the year. The bottom line: With modern forms of aquaponic/hydroponic farming, the land still rests, the farmers not so much.

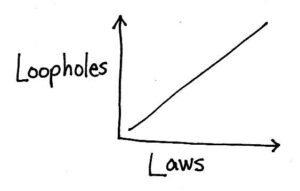

As stated above, two of the most famous examples of legal loopholes are found our parsha and though we have previously discussed a few of these gevaldige loopholes, it’s avada worthwhile doing a shtikel chazora (review) because loopholes are not concepts unique to the legal profession. Seemingly, they were first introduced many generations earlier by a few very smart rabbis who were forward thinkers. They have since become a mainstay of our Toirah observance. One could argue that legal loopholes may taka facilitate better observance. And while many argue and remain frustrated when technicalities change the outcome of a case, when certain people are presumed innocent or guilty as a result of political leanings, or because of a procedural technicality, it epes appears that even our rabbis of yore chapped that at times we need to more carefully examine both the letter and the spirit of the law and to see if there is any maneuverability. The bottom line: at times, being progressive is a good thing. And taka because of a few interesting mitzvis found in parshas Behar, these good rabbis sprang into action and whenever they felt that a particular mitzvah was no longer relevant or applicable, they developed a work-around, a hair-splitting way to deem it inoperative.

In other words: could we really be considered observant Jews absent of sanctioned loopholes? Would we, and could we survive without loopholes? Ober, are we suggesting that there are mamish loopholes around the RBSO’s mitzvis and commandments? Are they mamish legal? Seemingly they are! And to chap how, why and when they came about, lommer unfagin (let us begin) with a few laws about Shmita.

Besides the land restrictions, Shmita nullifies outstanding debts. It does what? It’s one thing to prohibit plowing – many have sadly become accustomed, if you chap, ober the nullification of debts? And the halocho (rule) is, or was azoy: at the end of a Shmita year, all loans or debts between Jewish people (men or women) that are due before Rosh Hashono, are cancelled. Over and done! Did you just read that one can borrow money from his best friend, wait seven years (even less if the loan was taken closer to a Shmita year) and then tell the lender that he’s not being paid because his loan expired due to Shmita? Indeed you did. This is called ‘Shmitas Kisaofim’ (a debt wipe-out, if you will). Moreover, not just is the loan wiped out but one is forbidden by a loi-sah-say (negative prohibition) from requesting repayment from the borrower. Requesting repayment of your loan after Shmita, the very one you provided in good faith before the Shmita year, is a no no! This includes debts resulting from monetary loans as well as those incurred from borrowing items that have been consumed. In other words: your money is gone!

On the other hand, why shouldn’t Shmita wipe out your loan? Where is it written that just because you were nice enough to advance a chaver (friend) a much-needed loan, that you’re entitled to get repaid? Don’t you know that no good deed goes unpunished? And this isn’t just a minhag (custom) but a din (rule). Want more bad news? Bazman Hazeh (in our times), even when the laws of Yoivel are not applicable, (according to most Halachic authorities), the mitzvah of Shmitas Kesafim (Rabbinic only) remains in effect. And taka why? Says the heylige Gemora: this was instituted so that these laws would not be forgotten from Israel. There’s more: It appears from the good books, that this ruling applies both in Israel and in chutz Lo’oretz (here), since it is an obligation dependent on the person (gavra) and not on the land (adomoh).

Shoin, what to do about this halocho? How do we operate? Would people lend money even for interest (we’ll get to that soon) in year six (or earlier) if they understood that such loans are subject to being wiped out in year seven? A nechtiger tug and avada nisht! Ober not to worry because Toirah/shmoira: the good rabbis of yore chapped that business is business and that the rules of shmita and loan cancellation would mamish shut down the money lending business and efsher the gantze (entire) economy. Who would support their local rabbis if they weren’t getting their loans repaid and couldn’t collect interest? Nu, when the parnosa (livelihood) of our rabbis was potentially affected, they came up with one of the cleverer loopholes ever created and named it the Pruzbil. And Chasdei Hashem (through the kindness of the RBSO), halocho makes use of “evasions” of the law in various different realms.

Ober where is it written that one should taka lend money to those in need? Nu…the heylige Toirah (Devorim 15:2; 9-10) says just so in discussing shmita and let’s learn the pisukim. “And this is the law of the Shmita; to release the hand of every creditor from what he lent his friend; he shall not exact from his friend or his brother, because the time of the release for the L‑rd has arrived … Beware, lest there be in your heart an unfaithful thought, saying, “The seventh year, the year of release is approaching,” and you will begrudge your needy brother and not give him… You shall surely give him, and your heart shall not be grieved when you give to him; for because of this the L‑rd, your G‑d, will bless you in all your work and in all your endeavors.” Shoin, case closed and lending is a must.

Nu, as you can see, the RBSO was worried about us having unfaithful thoughts, even about money issues. Says the heylige Gemora (Gittin) azoy: about a century before the destruction of the Second Beis Hamkidash (Temple) a man named Hillel the Zoken (the elderly) came up with mamish a gevaldige loophole, one of many that allow us Yiddin to survive on a daily basis. After all, the heylige Toirah does state Vo’chai Bohem (and you shall live by them) and avada we translate that to mean that if a law makes life so unbearable, we may find a way around it. Anyway, Hillel saw that people were avoiding lending, and because he didn’t want them to commit the avayro of not lending to those who needed help (a sin mamish described above), as the Shmita year approached, he came up with this brilliant chap (novel idea).

How does it work? Like a loophole should! The Toirah tells us that only private debts are cancelled by Shmita: “He shall not exact from his friend or his brother.” Read those words again. If, however, one owes the court (i.e., the community) money, Shmita does not affect the loan. Based on the wording of the heylige Toirah, Hillel instituted the “pruzbil”: a mechanism by which debts are magically transferred from the individual to a Beis Din (religious court). By making a pruzbil, one makes his private debts public – and therefore redeemable. Shoin no SEC, no IPO- gornisht (nothing). Want to go public? A Simple Pruzbil does the trick. Exactly how the funds are collected by the Beis Din and how they are repatriated to the original lender, ver veyst, but one has to assume that after a proper vig is paid to the Beis Din, the rest somehow makes its way back. Actually, as the Ois understands the mechanics- once the loan is declared as now belonging to the beis din (with the pruzbil), you can actually collect it yourself. And as to why Hillel was allowed to enact this loophole, we are taught that there was a pressing need. Mistama a concept similar to hefsed meruba (big losses) which did away with sefira and other restrictions and one that will soon allow shuls to swipe credit cards on shabbis following an appeal or an Aliya when one makes a pledge.

Avada you’re totally bewildered at Hillel’s actions for who empowered him to go against what the heylige Toirah’s demands? And as you can only imagine, the Gemora has lots to say on this inyan. And not just the Gemora, for generations since, they’re still discussing Hillel’s bold move, the issues and its mechanics. And says Toisfis (a commentator on the heylige Gemora) azoy: there was mamish no concept of Shmita or Yoivel during the 2nd Beis Hamikdash because a majority of the Yiddin were living outside of Israel, a concept we covered earlier. Hence Hillel did nothing wrong. Others says Hillel was not the creator of this loophole and that he was merely given credit because he publicized an already existing loophole in the Toirah which allowed private debt to be converted into court debt. In other words: Hillel, mistama the first Jew in that position, was acting like the Federal Reserve during a crisis in order to allow the banking system to work for the Yiddin. Shoin, who should it work for, the goyim? Of course you’re now wondering what will happen if and when the Moshiach arrives. Will we need loopholes if they bring back Shmita and Yoivel? Is Hillel coming back? Ver veyst?

And listen to this vichtiger (important) nikuda (point). There are various types of debts which do not require a pruzbil and can be collected after shmita even without the paperwork. Lemoshol (by way of example), debts which arise as a penalty or fine — such as the money a man must pay his victim for rape or seduction. You can see just how clever our sages were, they chapped even back then that the menner (men) were shlecht (bad boys) and had to make provisions for their victims to be able to collect. Also, a woman’s kesubah (marriage contract) may be enforced. There are a few others but do I expect you to concentrate once you read about seduction? Zicher nisht! Go look them up. Veyter and let us – bikitzur (in short)- cover the next beautiful loophole in this week’s parsha: the famous heter Iska. And what is a Heter Iska?

In our parsha, we learn that the RBSO wants us -in fact, He exhorts us- to assist other Yiddin financially, and prohibits us from charging interest on these loans. Says the Chofetz Chaim that every Yid should grant another Jew an interest-free loan, and recommends that each person apportion some tzedokoh money for granting such loans. As an aside, it is perfectly permissible, however, for a person to invest money in a Jewish business, and to share proportionally in whatever profits or losses there may be.

And to accommodate the over 99% of us that can’t/don’t give such loans, nu- it’s time to introduce for a second time – the heter iska. What is it? Today all that’s necessary to circumvent the law of not charging interest to another Yid, is to sign a heter iska, a document ‘invented’ by our good and thoughtful rabbis, that converts a loan into a business partnership From research the heylige Ois has been busy with, it appears that the idea of the heter iska arose way back in the seventeenth century, and expanded to enormous proportions over the last hundred years, despite its inherent halachic difficulties, ober as we say over and again: business is business and seemingly, there was little interest (pun intended) in conducting business without real interest. It works like this:

In a heter iska, the “lender” and the “borrower” turn into “investor” (capitalist) and “businessman.” Thus, it is noted that all the documents mentioning the terms “borrower” and “lender” actually mean “investor” and “businessman.” Shoin: a new title and you’re good to conduct business. The investor gives money to the business, and the businessman is supposed to invest the money in a business that yields profits. The profit and loss derived from the money is divided equally between the investor and the businessman, except for the small salary that the businessman takes for his work. The important point in the agreement is that the investor cannot know exactly how much the businessman profits from the business, and so the parties agree among themselves that the businessman is required to prove the truth of the figures presented by him. If the businessman is unable to prove to the investor how much money he earned, he must pay him demei hispashrus, at the rate of interest. Practically speaking, the businessman (i.e., the borrower) is unable to prove how much his business profited or lost, and therefore he must pay the investor (the lender) the agreed upon demei hispashrus. In other words: a givaldige loophole being used bazman hazeh (in our times) on a daily basis. In fact, banks with branches in heavily orthodoxy communities advertise the heter iska and offer it to all their depositors No more toasters, beach chairs or corning ware: today with your loan, you get only a heter iska! And I kid you not!

Nu, as you can see, our sages of yore were capitalists, they chapped business and they chapped that without creating loopholes, the gantze yiddishe economy might collapse. Were they not mamish brilliant? Did they not sit and ponder and figure out how to make life easy for us back then? They did! We need to bring them back, or, find others in our times that chap these lofty ideas. The final bottom line: The emes is that legal loopholes are part of the Divine system, maybe what the RBSO had in mind. And for good reason. The legal loophole is a mechanism to resolve tensions between conflicting values, a way of remaining faithful to the eternal laws of the heylige Toirah while being responsive to the needs of the time.

A gittin Shabbis-

The Heylige Oisvorfer Ruv

Yitz Grossman