Raboyseyee and Ladies,

Yoisef’s Clean Hands and or, Cold Revenge

Did Yoisef have clean hands? Was he -at all times- but the victim? Is he deserving of the appellation Yoisef Hatzadik (the righteous)? Or, was his own behavior -at least at times- somewhat questionable? What about clean fingers? We shall explore this below but let’s begin here.

According to leading sources -the heylige internet of course- the accepted meaning of “revenge served cold” is this: it’s revenge carried out slowly, deliberately, and without emotional outburst — often long after the original offense — so that it is more calculated, controlled, and psychologically devastating. In contrast to hot-blooded revenge (anger, impulse, shouting), cold revenge is: patient, strategic, emotionally restrained, often disguised as justice or neutrality. The classic idea is that waiting removes passion but sharpens impact. The phrase is most commonly traced to the French: « La vengeance est un plat qui se mange froid » “Revenge is a dish best eaten cold.”

Ober, is that emes? This week the heylige Ois will argue that the French but copied the heylige Toirah where it appears that Yoisef was the first Toirah personality to concoct the dish and serve it mamish cold. That stated, the French are certainly original when it comes to fashion, baguettes, etc., and though their history does include cold revenge, originality in this category is not their strong suit. More on cold revenge later, but we begin here and welcome to one of the most emotionally charged parshas in all of Sefer Bereishis.

Yes, the Akeidah still holds the gold medal for raw terror — Avrohom gripping the knife, Yitzchok bound like a sheep, the Malach Hashem (angel) screaming stop. But the emotional implosion of Vayigash runs a close second. The moment Yoisef can no longer sustain his charade, the moment power collapses into tears, the moment brothers realize that history has been staring at them the whole time — it is riveting. It’s mamish goosebump Heylige Toirah.

And yet, every year as Vayigash approaches and we emotionally prepare ourselves for reconciliation and forgiveness, the heylige Ois must ask the question no one wants to: Was Yoisef better than his brothers? Or did he simply have better leverage? Was he always the victim? Or, did he at times also victimize others? Did power make him forget his own father and beloved brother Binyomin? Did he dole out cold revenge and serve it Egyptian-Style? Though Yoisef, is kimat everyone’s favorite Toirah personality, movies – made for TV, the big screen- and Broadway shows about his life notwithstanding, let’s be honest, he does not look like a saint in this parsha.

He torments his brothers methodically. He accuses them of espionage. He jails Shimon. He engineers Binyamin’s arrest. He stages a fake crime. He keeps them dangling emotionally and legally. He watches them squirm. And he does all of this while fully aware of their family trauma and his father’s grief. This is not impulsive rage. This is cold, calculated revenge. How does he treat his innocent brother Binyomin, the only one he shared with his mother Rochel? The very one who was absent when he was mercilessly stripped of his cloak, thrown into a pit, and then sold into slavery for some silver coins? How is Binyomin treated? One could argue that Binyomin is the most haunting figure in Vayigash. Why is that? Because things just happen to him. He does not speak. He does not act. He is arrested, framed, threatened, and nearly enslaved — all without agency. Binyomin becomes the moral litmus test for everyone else.

But wait, there’s more. Let’s forget the holy brothers for a moment; what about his own father? Did Yoisef, at his first opportunity, contact him? Seek to make contact? Go see him? Don’t leaders travel all over the world during their reign? Don’t they have emissaries? Indeed, they do. It’s not like Egypt was that far from K’nan. Farket, it was quite close. How close? Let’s see. Roughly speaking, Southern Canaan → Nile Delta (Goshen area): ~200–250 miles. Let’s be generous, an even 300 miles away. In ancient terms, a camel caravan travels about 20–30 miles per day so the trip would take roughly 8–14 days, maybe 2–3 weeks at a relaxed pace. His father’s house was not remote or unreachable. Ober, was messenger travel normal in Yoisef’s time? Absolutely yes. Egypt had advanced bureaucracy, messengers, scribes, sealed letters. Paroy communicated across regions. Merchants, diplomats, and supply caravans regularly traveled between Egypt and Canaan. Yoisef himself managed international grain distribution — meaning cross-border logistics were routine. The bottom line: the idea that “Yoisef simply couldn’t get a message to Yaakov” as put forth by some, is not historically credible once Yoisef was in power.

And even if Yoisef could not travel for whatever reason – let’s say he would have needed Paroy’s permission and it wasn’t forthcoming, or let’s even kler (think) that Yoisef didn’t want to expose himself as a nice boy from the Yaakov Ovenu clan, could Yoisef not have sent a messenger by camel? He was the second in command! Zicher and 100%! Not only could he have — it would have been logistically easy, politically acceptable, administratively trivial. A single sealed message: “I am alive. Do not mourn. More to follow.” That alone would have changed everything. Or, couldn’t he have told this to the brothers the first time he recognized them? Yes, he could’ve but made the choice not to.

After Yoisef’s big reveal he instructs his brothers to return to their father with instructions to uproot himself and move with his entire family and belongs over to Mitzrayim where Yoisef -now in power- will take care of their needs. Ober the question that’s been asked above and for many generations is this: why didn’t Yoisef ever contact his father? It’s taka emes that he was unable to make contact during his enslavement or transport while being sold from group to group until his arrival and sale to Potiphar. On the other hand, it’s very bavust (known) that kimat everyone in prison has access to phones and even cell phones; what’s pshat?

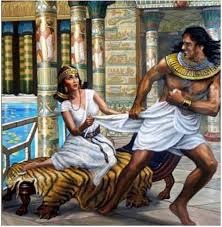

Moreover, even before prison, while running Potiphar’s household – yes, he was seemingly in charge there too, and had free reign to do as he pleased -even with Mrs. Potiphar who took a shine to him, if you chap. He could have asked her -or his boss Potiphar who also loved his and trusted him- for this shtikel favor? How could this holy roller who tells Paroy that only the RBSO can help decipher dreams, not have made some arrangements to have his father know that he’s alive and well? Did Yoisef do this intentionally? Was he without fault while his elderly father was left bereft of his favorite son? Let’s get real: Yoisef has at least 9-10 years -maybe more- when he could have made contract; that’s a long time!

The good news: Our holy Sages (Chazal) broke this all down for us, let’s be precise and fair. Yoisef could not have contacted his father for much of those twenty-two years. Approximately thirteen of them were spent enslaved or imprisoned. Those years are not on him. But the Heylige Toirah is not interested in what he (that, as an aside includes us) couldn’t do; only in what he/we chose not to do once we finally could. Yoisef didn’t have twenty-two years of freedom but he did have close to a decade of unchecked power. And it is there, not in the dungeon, that the Heylige Toirah begins its quiet accounting. The timeline is this: Yoisef was 17 when sold, 30 when he stood before Paroy (Miketz). That’s 13 years lost to slavery in Potiphar’s house and imprisonment. The bottom line: one could rationally argue that for at least 10–13 years, Yoisef literally could not contact Yaakov. He gets a hall pass. That part is not on him. Ober, once freed, he oversaw 7 years of plenty and 2 years of famine before the brothers arrived. That’s roughly 9 years of power before the reunion. So, the real question is not “why didn’t Yoisef call for 22 years?” It’s: Why didn’t Yoisef call for those 7–9 years when he clearly could have?

The big news is that a good number of sages hold him accountable for the years of power because distance was not the barrier, technology was not the barrier and politics was not the barrier. The barrier was choice. Canaan wasn’t Mars. A camel with a note could have ended Yaakov’s mourning in under two weeks. Geography didn’t keep Yoisef silent; choice did. How could Yoisef, whom so many refer to as “Yoisef Hatzadik,” not let the family know that he was alive, well, and much more? He waited how long to reveal himself? What’s pshat here? What Tzadik acts this way?

Moreover, where in the heylige Toirah -aside from Noiach- do we see the appellation Tzadik attached to a name? And the answer raboyseyee is this: We don’t! Case closed. It’s mamish made up by our sages and let’s take a shtikel dive into this matter and begin with the bottom line: In the Heylige Toirah itself, only one person is explicitly called a “tzaddik” and that’s Noiach. Yoisef is never called a tzaddik in the Chumash. “Yoisef HaTzaddik” is a title given later by our sages of the medrish, and in Kabolo. Ok, let’s slow that down as we harken back to Noiach where we read (Bereishis 6:9) this explicitly “נֹחַ אִישׁ צַדִּיק תָּמִים הָיָה בְּדֹרֹתָיו” “Noiach was a righteous man, wholesome in his generations.” That’s it. No Avrohom. No Yitzchok. No Yaakov. No Moishe. No Yoisef. Just Noiach. Moreover, the sages famously argue whether that’s real or faint praise (“in his generation”). The bottom line on Yoisef is this: he was not a Heylige Toirah-Tzaddik, but a Chazal-Tzaddik. The Heylige Toirah describes Yoisef as: successful, handsome, favored, clever, morally restrained (with Potiphar’s wife), but never calls him a tzaddik.

How did he earn this title? Primarily because he resisted sexual temptation (kedushas habris), more on that soon. As an aside, now you chap why none of you will ever be referred to as a Tzadik, no matter how much tzedoko you give, how many committees you join, how much you shokel during davening, and the list goes on. The issue of what you’ve been shokeling, if you chap, will always stand in your way. How many of us have properly guarded the bris, if you chap? Case closed! And shoin. Veyter!

As mentioned, the title appears repeatedly in the medrish and heylige Gemora, especially in connection with Yoisef’s sexual restraint. Says the medrish (Bereishis Rabbah 87:8), azoy: “יוסף נקרא צדיק על שעמד בניסיון”– Yoisef is called a tzaddik because he stood firm in the test. Seemingly just standing firm was also an issue; more on that below. The medrish refers specifically to Eishes Potifar. The heylige Gemora (Sotah 36b–37a) tells us that Yoisef is explicitly grouped with Boaz as men who overcame sexual temptation and are therefore called tzaddikim. That same shtikel also includes the famous image of Yaakov’s visage appearing to Yoisef as he was about to succumb to Mrs. Potiphar’s advances and how Yoisef nearly failed. He succeeded at the last moment and this is where the tzaddik title becomes entrenched. Gishmak. In the heylige Zoihar (Kabbalistic), Yoisef is identified with Yesod, the channel of moral and sexual integrity, the archetypal tzaddik despite internal struggle. Says the Zoihar very clearly that Yoisef is a tzaddik because he struggles, not because he is flawless.

The bottom line is this: Chazal do not call Yoisef a tzaddik because he was nice to his brothers, because he forgave easily, or because he was emotionally generous. They call him a tzaddik because he controlled himself when no one would ever know, he did so alone, in exile, without family, without accountability. Yoisef was a tzaddik in the bedroom, not necessarily in the boardroom. His righteousness lies in what he did not do, not necessarily in how gently he treated those who once hurt him.

As to why the Heylige Toirah withholds the title, might we suggest -with more than adequate cover from well-known and holy exegetes, as well as our sages of yore, that the heylige Toirah refused to canonize Yoisef as morally spotless davka because he manipulated his brothers, he inflicted emotional suffering, he delayed contact with his father and he weaponized power. Wow! What sayeth our fearless Sages and others about Yosief’s odd behavior? Did they clean him up as they did Loit’s daughters who took turns fornicating with their father? Avada you recall that many an exegete called them “Noshim Tzidkonious” (righteous women)? Would you use that terms in similar circumstances? Oy vey! Notice the word comes from “tzaddik.” We all still love him and he remains -avada- kimat everyone’s favorite Toirah personality. That stated, let us read what a few had to say:

Says the Ramban (Bereishis 42:9) who is quite explicit: Yoisef was actively orchestrating events to fulfill his dreams; not merely letting things unfold. Ouch! Yoisef should have informed Yaakov immediately. Causing his father prolonged anguish was unjustifiable, and that Yoisef’s tests went too far. Ouch again! Yoisef remembered the dreams and then acted in ways that forced their realization. This is not passive providence; it is human engineering in the service of destiny.

The Ibn Ezra, suggests psychological fear rather than revenge. Yoisef knew exactly what he was doing — and Heylige Toirah wants us to know that too. He remembered the dreams, and then he made them happen. Dreams that required humiliation, fear, and submission. The medrish (Tanchuma) criticizes Yoisef for unnecessary cruelty. The Zoihar hints that Yoisef’s suffering did not end with his rise, it merely changed form. Power does not erase trauma; it often calcifies it. Yoisef had options. He had authority. He had years. And yet he chose silence. Which leads us to the next uncomfortable truth.

The Abarbanel questions Yoisef’s moral calculus: Testing repentance does not require deception at this scale. Yoisef risks permanent damage to the family. Leadership does not grant license for emotional experimentation. This is a strong critique from a political thinker. And given all that, why taka do our Sages refer to him as Yoisef the Tzadik? What’s pshat? It’s azoy: Chazal call him a tzaddik in a specific domain. His strength when it came to sexual restraint, and covenantal endurance. Nu, if Loit’s daughter who mamish fornicated are called Noshim Tzidkonius, we should have no issue calling Yoisef a Tzadik if he withstood the test of an aggressive woman trying to have her way with him! The Ois is good with his own pshat!

Speaking of clean hands which include fingers, and though the heylige Ois has mentioned this particular pshat in the past, so happens that in shul just yesterday (it’s Sunday and the Ois is on draft one), a reader who loves to critique the Ois yet reads weekly for a bunch of years, reminded me of a medrish which tell us that not just were Yoisef’s hands not so clean, neither were his fingers. Again, this particular medrish only, is a repeat and what the medrish (Bereishis Rabbah 87) says is mind boggling. As an aside, the same medrish is echoed in the heylige Gemora (Sotah 36b) and later Midrashic compilations.

There we read this more than amazing and alarming medrish which Rashi actually references and here it comes: In next week’s parshas of Vayichi, Yaakov will give his favorite son Yoisef some parting brochos (blessings). Let’s pay special attention to Rashi who says something so outlandish, it’s mamish hard to picture. Then again for many of you, it’s second nature. Let’s see what he says in the shaded box below- read this carefully:

| the one who was separated from his brothers: Heb. נְזִיר אֶחָיו [Onkelos renders:] דַאִחוֹהִי פְּרִישָׁא, who was separated from his brothers, similar to “and they shall separate (וַינָּזְרוּ) from the holy things of the children of Israel” (Lev. 22:2); [and ]“they drew (נָזֹרוּ) backwards” (Isa. 1:4). – [From Sifra Emor 4:1] [Returning to verse 24, Rashi continues:] Our Rabbis, however, interpreted“ But his bow was strongly established” as referring to his (Joseph’s) overcoming his temptation with his master’s wife. He calls it a bow because semen shoots like an arrow. וַיָּפֹזוּ זְרֹעֵי יָדָיו [וַיָּפֹזוּ is equivalent to וַיָפֹצוּ, scattered, that the semen came out from between his fingers.] | נזיר אחיו: פרישא דאחוהי, שנבדל מאחיו, כמו (ויקרא כב ב) וינזרו מקדשי בני ישראל, (ישעיה א ד) נזורו אחור. ואונקלוס תרגם תאות גבעת עולם, לשון תאוה וחמדה, וגבעות לשון (שמואל א’ ב ח) מצוקי ארץ, שחמדתן אמו והזקיקתו לקבלם: |

Stop the presses right now and let’s look at the last 7 lines of Rashi again please. What? Semen came out from between his fingers? What is going on here? Where and how did semen make its way into the parsha and into Rashi? And what’s this bow and arrow talk in the parsha, is it Lag B’oimer? Nu, zorg zich nisht (don’t be worried) and let’s learn pshat. Says the heylige Gemora (Soitah 36B) azoy:

Yoisef was sold as a slave to Potiphar. Potiphar’s wife tried to seduce him, and although he initially rejected her advances, he eventually gave in and seemingly also went in, if you chap. Say it’s not so please! As he was about to complete the illicit act of relations with the seducer- shrecklich mamish (OMG) – the image of his father suddenly became fixed in his mind, and he relented. Said Reb Yoichonon azoy: “His strength was firmly founded” –meaning- his Ever (member) was erected. “And gushed out from his hands” – he stuck his hands in the ground, and the semen came out from between his fingernails. He dug his fingernails into the ground to control himself, and miraculously, the flow of semen issued from his fingers into the ground instead of issuing into Potiphar’s wife. Well, blow me down! Shoin, is it a wonder that people all over the world now carry their Gemora wherever they go? Can’t believe what you just read? Let’s learn it noch a mol (one more time). Seemingly (maybe), Yoisef did sin in thought, and drops of his semen issued from between his fingernails, but he did not complete the evil act by injecting [his seed] into that foreign woman. Therefore, his skeleton was buried in Israel but not his body. As an aside, the Marsho suggests that the semen did escape from its usual source; avada this you can understand.

The Gemora, quoting a Breysa goes on to say that in the original master plan, 12 Shvotim were to have descended from Yoisef (like from Yaakov), but since the semen exuded from his (10) fingernails, he merited only two sons. Seemingly the rest of his juice slipped through his fingers. Efsher, had his zerah come from and gone into the right places, he would have taka had another 10 children; ver veyst? Whatever happened or not, is none of our business and zicher no excuse for you to ever put yourselves in a situation where semen can come out of your eyver, fingernails, or any place else, and end up in the wrong place. Of course, if it does, Yom Kippur is not far off.

And the question is this: Why was Yoisef still punished? He mamish did his best to resist and yet he gets punished? What’s pshat? Seemingly, they hold Yoisef accountable not for the act — but for allowing himself to reach that edge. In their moral calculus, Yoisef won the battle but lingered too long in the war zone. Confucious might have said it azoy: When one lingers, evidence found on fingers. What was the punishment? Chazal identify three consequences, all subtle, none catastrophic: 1. Delay in his release. The heylige Gemora (Sotah) links Yoisef’s continued imprisonment to this episode — not as vengeance, but as spiritual recalibration. 2. The heylige medrish says Yoisef loses one letter from his name temporarily (from Yoisef to Yoisef-minus-a-ה), signaling diminished spiritual stature. Measure-for-Measure Isolation. Just as Yoisef endured intense inner conflict alone, he later experiences prolonged emotional isolation, even as ruler of Egypt. His success did not cancel consequence.

All that said, we must chap that even this tiny infraction does NOT and did not undermine Yoisef’s Greatness. This medrish does not say Yoisef sinned like Potiphar’s wife wanted. On the contrary: Angels argue over him, he resisted in exile, and he preserved covenantal identity. That is exactly why our sages call him Yoisef HaTzaddik. And here is the good news for all us: our sages do not believe tzaddikim are superhuman. Instead, they believe tzaddikim are accountable even for microscopic moral failures. The very good news for all of us is this: we are not tzadikim and need not worry about being judged for microscopic failures.

The Ois has long argued that Yoisef was not innocent and that greatness does not erase damage. Yoisef was not a monster, Yoisef was not innocent, Yoisef was a human being operating inside divine destiny. Let us recall what the RBSO told Avrohom: “גר יהיה זרעך בארץ לא להם” “Your descendants will be strangers in a foreign land.” That promise required: exile before nationhood and dysfunction before destiny. Yoisef was but the bridge.

And the final bottom lines? Yoisef mastered over desire and his domain, if you chap. In other words, in the matter of Mrs. Potiphar, Yoisef had clean hands. The tragedy of Vayigash is not that the family was broken. It’s that no one in the family was innocent. The nice news: the heylige Toirah is real and still insists on telling the story. His story and the others in Bereishis (and throughout Tanach which records most of our inglorious -at times- history just proves that the RBSO advances history not through perfect families or individuals, but through broken people who refuse to break entirely.

A gittin Shabbis!

The Heylige Oisvorfer Ruv

Yitz Grossman