Raboyseyee and Ladies,

Oral Spankings & Tough Love

Shoin Rosh Hashono is behind us and for many of us, a few more pounds are suddenly in front of us. Fasting on Yom Kippur will help moderately but the coming Sukkis holiday is mamish staring us in the face and so are the extra pounds! Ozempic please!

The term “reverse psychology” was first coined in the 1930s–1940s in the context of psychological studies on human behavior, particularly by psychologists studying reactance—the tendency for people to resist being told what to do. While the practice itself (encouraging the opposite of what you want) is much older and has been used informally for centuries, the actual phrase “reverse psychology” started appearing in English around that time, often in child psychology and social psychology literature.

That information is readily found online, ober is this emes? Reverse psychology was only introduced less than one hundred years ago? Not exactly! The Ois will argue that reverse psychology has been around for thousands of years and was first introduced by Moishe and used by him with some frequency beginning in the year 2448- and until his last day in the year 2488. Get ready and here we go.

Let’s set the scene: As parshas Vayelech opens, it’s Moishe’s birthday and his last day on earth. He’s 120 years old. How is he celebrating? There will be no farewell dinner, no commemorative plaques, no shul dinner with the band playing “Moishe Emes, Vi’soirosoy Emes.” No speeches about his forty years of service, no slideshow with baby pictures of Moishe floating along the Nile in his custom-made basket. Not even a sheet cake with “Happy 120th Moishe!” written in blue icing. Instead, on this day, he gathers the entire nation – all the Yiddin mamish- and delivers what has to be the most brutal farewell speeches in history, mamish an oral spanking! Let’s read the posik innaveynig from our parsha (Devarim 31:27):

כִּי אָנֹכִי יָדַעְתִּי אֶת־מֶרְיְךָ וְאֶת־עָרְפְּךָ הַקָּשֶׁה הֵן בְּעוֹדֶנִּי חַי עִמָּכֶם הַיּוֹם מַמְרִים הֱיִיתֶם עִם־יְהֹוָה וְאַף כִּי־אַחֲרֵי מוֹתִי

For I know your rebelliousness and your stiff neck. Behold — while I am still alive with you today, you have been rebellious against Hashem; and surely after my death [you will be even more so].

In plain Brooklyn English: “Moishe basically says — Listen, I know you guys. You were wisenheimers even while I was still around keeping an eye on you. So what do you think is gonna happen when I’m gone?” It’s Moishe’s last “I know you better than you know yourselves” moment, and it’s a real schmeissing. After forty years of leading them, calming them, and taking the heat for them, he flat-out tells them: I know your track record. I’ve seen the eygel (golden calf), and lived through the spies, the complaints about food, water, meat… You think you’re going to suddenly get better without me? Ha! The bottom line: “You guys were trouble while I was alive, and you’ll be worse once I’m gone.” I know your shenanigans.

Well blow me down! Imagine the Rav of your shul, any Rabbi of any shul, giving this speech at his goodbye kiddush. Do you think for even a minute that the sisterhood would still present him with a silver menorah? Fuhgeddaboudit.

We usually expect leaders to close out their careers with warmth, gratitude, and love. “It’s been an honor serving you, I’ll miss you, stay strong, keep the faith.” Not Moishe and not in this week’s parsha. His last recorded words to the people? A stiff slap across the face, ah drik in tuchis (a kick in the ass). No hugs, no kisses, just: “You’re stubborn, you don’t listen, and you’ll only get worse.”

And here’s what makes it even more shreklich (OMG moment): this was not just another canned speech. This was his deathbed. His very last day alive. The people surely expected blessings, words of encouragement, maybe even some reminiscing about the many miracles along the way. A look back to how far they had come, how much progress they had made as they stood mamish on the precipice of finally entering the Promised Land. Is that what happened? A nechtiger tug and fuhgeddaboudit! Instead, Moishe leaves them with a verbal spanking. The last thing they thought they’d hear as he took his leave from this world was: “You’re a bunch of no-goodniks.”

The same Moishe — the man who shattered the luchos, davened to the RBSO for forgiveness, begged for them not to be wiped out, and took endless abuse from his flock — was now giving them one last reality check. And you know what? After forty years of babysitting a nation of millions, maybe we shouldn’t be surprised.

Moishe calls the Yiddin “stiff-necked” — עַרְפְּךָ הַקָּשֶׁה, ober what does that mean? Says the Sforno that the Yiddin could not be turned to the right path easily. They are firm in their errant ways. Says Rashi that they were rebellious even while Moishe was alive. Says the Mlabim, azoy: stiff-necked means not merely sinning impulsively, but rooted rebellion — a refusal to change course even when shown truth. Yikes! The Sifrei adds that Moishe knew their character too well: over his forty years of leading them, he experiences the eygel, miraglim (spies), food complaints, water shortages, quail riots, and the Koirach rebellion, an attempted coup mamish. We forgot to mention the orgy with the Moabite and Midianite shiksa whores. He had his hands full. One could argue that by the time he got to Parshas Vayelech, Moishe had seen every shtick in the book. The Yiddin were a crafty bunch who seemed to move from one calamity to another, angering the RBSO on many an occasion. As well, they got under his skin more than once.

On the other hand, forty years of leading this crew was no easy task. That’s not a contract; that’s a prison sentence with hard labor. Many a rabbi would have quit or retired to Florida after year two. Moishe stuck it out for four decades. That makes him one of the, if not the longest-serving rabbi in history — and the most underappreciated. The bottom line: none of todays rabbis have it nearly as bad as did Moishe.

On the other hand, let’s get real: this was not the first time Moishe used these words. Farkert: this was the last and let us quickly review other references to the stubbornness of these stiff-necked people. As it turns out, he had a whole series of zingers going back to Sefer Shmois and a few earlier in Sefer Devorim. Here are some of his “greatest hits” of rebuke and smackdown:

Let harken back to the eygel incident where we read this (Shmois 32:9): the RBSO states: רָאִיתִי אֶת־הָעָם הַזֶּה וְהִנֵּה עַם־קְשֵׁה־עֹרֶף הוּא “I’ve seen this people, and behold — they are a stiff-necked people.”

Moishe repeats it to remind them of their stubbornness even at Sinai.

Wait, there’s more: in fact, there are three more mentions just before this week’s parsha where Moishe tell the Yiddin of their stubbornness and stiff necks.

9:6: “Know that Hashem does not give you the land because of your righteousness, for you are a stiff-necked people.”

9:13: “I have seen this people, and behold, they are a stiff-necked people.”

10:16: “Circumcise the foreskin of your heart, and do not harden your neck any longer.”

The bottom line: Moishe reminds the people over and again that they’re not getting the land because of their good behavior. It’s farkert (just the opposite). Their behavior was mostly abhorrent, but despite their shtick, they have been chosen to enter. But, knock off the narishkeyt.

And guess what? Though it’s taka Moishe’s last day, the day does extend into next week’s parsha of Ha’azenu (Devorim 32:5 ) which we will read after Yom Kippur and before the next eating festival of Sukkis and where Moishe will offer these choice words in his swan song: “They are a generation crooked and twisted.” Not exactly the kind of lyrics you’d want sung at your going-away party.

The bottom line: Moishe’s oral “spankings” always circle back to three words:

- ממרים (rebellious),

- קשה עורף (stiff-necked),

- מרי (rebellion / defiance).

He’s consistent and always delivers the same message! Moishe had no shortage of examples to share and the Yiddin must have felt like kids with the world’s strictest rebbe. Every word out of his mouth in recent weeks was harsh and the question is this: was this effective leadership? Was Moishe constantly reminding the people of their stiff neck behavior, effective in getting them to change? It appears not! And if that’s the case, why didn’t he change course? Why not try some positive reinforcement? Some honey? A few gold stars for good behavior? Let’s get real: the Yiddin knew they were stiff-necked and yet didn’t change! Would Moishe have fared better and gotten better results had he given them some positive praise?

On the other hand, efsher we can argue that Moishe was efsher the first psychologist and the first to use Reverse Psychology 101. Efsher we can argue that Moishe wasn’t just insulting them but that his words were those of a master psychologist. He knew that if you tell a Jew, “You’re hopeless, you’ll never make it,” that the Yid will dig in his heels and prove you wrong. That’s the Jewish way. Tell a Jew he can’t park there or sit in a particular seat, and he’ll fight till Moshiach comes. Tell him he’s not good enough for Toirah, suddenly he’s at the early morning Gemora class, soaking up the daf. The examples are limitless. What to do? So Moishe, with his last breath, goes for reverse psychology. He tells them: “You’re a disaster, you’ll mess up without me.” But under the surface, he’s daring them: “Prove me wrong, wiseguys.”

And let’s be honest — it worked. We’re still here, stiff-necked as ever. Sometimes the very stubbornness that made us rebels is what kept us going through our darkest hours. Perhaps it keeps us Jewish through exiles, pogroms, and persecution. Perhaps we are living through such times right now; we need that stiff necked attitude. And taka says the medrish (Tanchuma), azoy: the stiff neck can be a curse, but also the secret to Jewish survival.

And if that theory holds water, one can easily argue that in the end, Moishe’s “roast” was love in disguise. He knew the people so well that he could see their failures before they happened. And by voicing them out loud, he turned those failures into challenges. “You’ll mess up after I’m gone.” Translation: “Now prove me wrong.”

And perhaps that’s why he was brazen enough to remind the Yiddin mamish on his deathbed, and several more times in the last weeks of his life. Ober, had this been his only message over the entire forty years, the Yiddin might have brushed it off as another shpiel from their leader. But on the very last day of his life, every word carried eternal weight. His final rebuke wasn’t to crush them — it was to etch his voice into their conscience forever.

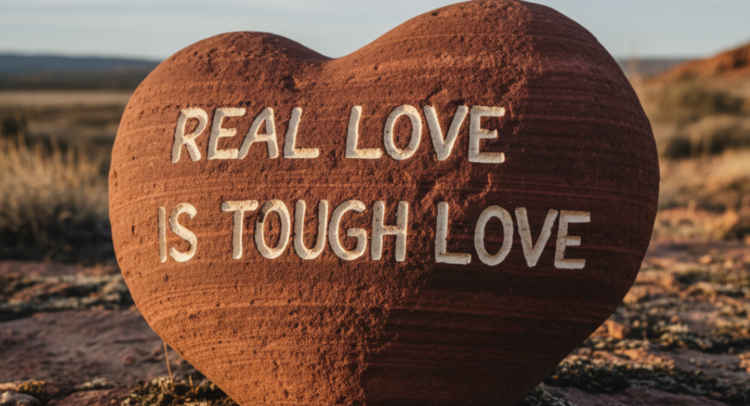

Was this the warm goodbye the Yiddin wanted? No. But it was the goodbye they needed. Because love isn’t always hugs and kisses. Sometimes love is the sharp slap that wakes you up. Moishe wasn’t abandoning them; he was embedding his voice in their conscience forever.

The final bottom line: The next time someone tells you Jews are stiff-necked, take it as a compliment, say thank you. Tough love is still love! That same stubborn streak Moishe cursed is the very reason we’re still around to read his words. Moishe’s last message wasn’t despair. It was challenge, hope, and the deepest form of love. And maybe — just maybe — the biggest compliment of all.

A gittin Shabbis!

The Heylige Oisvorfer Ruv

Yitz Grossman