Raboyseyee and Ladies,

Holy Men, Complicated Marriages:

What’s on my mind this week? It’s Avrohom’s wife, the one he marries -or remarries- approximately three years after Soro’s passing. Let’s say hello to Ketura or Hogor. Which is it? We shall soon find out. Settle in, it’s a very long one!

We begin this week’s incredible parsha of Chayei Soro which features several emotional storylines, by reading a few pisukim from the very end of the parsha: let’s get right to them and then try to chap what took place and why, but first, let’s set the scene:

Avrohom’s wife Soro passes away at the age of 127. He’s 10 years older. By the end of the parsha, Avrohom is a mature and ripe 140 years of age. Ober, has he slowed down? Retired? Moved to Miami, Boca, or Boynton? Not! Instead, he begins a new life. Let’s read the pisukim (Bereishis 25:1–6):

א. וַיֹּסֶף אַבְרָהָם וַיִּקַּח אִשָּׁה וּשְׁמָהּ קְטוּרָה׃

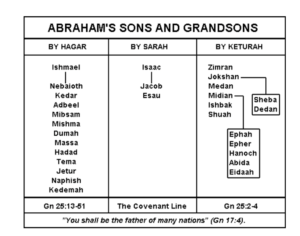

ב. וַתֵּלֶד לוֹ אֶת־זִמְרָן וְאֶת־יָקְשָׁן וְאֶת־מְדָן וְאֶת־מִדְיָן וְאֶת־יִשְׁבָּק וְאֶת־שׁוּחַ׃

ג. וְיָקְשָׁן יָלַד אֶת־שְׁבָא וְאֶת־דְּדָן וּבְנֵי דְדָן הָיוּ אַשּׁוּרִים וּלְטוּשִׁים וּלְאֻמִּים׃

ד. וּבְנֵי מִדְיָן עֵיפָה וְעֵפֶר וַחֲנוֹךְ וַאֲבִידָע וְאֶלְדָּעָה כָּל־אֵלֶּה בְּנֵי קְטוּרָה׃

ה. וַיִּתֵּן אַבְרָהָם אֶת־כָּל־אֲשֶׁר־לוֹ לְיִצְחָק׃

ו. וְלִבְנֵי הַפִּילַגְשִׁים אֲשֶׁר לְאַבְרָהָם נָתַן אַבְרָהָם מַתָּנֹת וַיְשַׁלְּחֵם מֵעַל יִצְחָק בְּנוֹ בְּעוֹדֶנּוּ חַי קֵדְמָה אֶל־אֶרֶץ קֶדֶם׃

“And Avrohom again took a wife, and her name was Keturah. And she bore him Zimran, Yokshan, Medan, Midyan, Yishbak, and Shuach… And Avrohom gave all that he had to Yitzchok. But to the sons of the concubines that Avrohom had, Avrohom gave gifts, and sent them away from Yitzchok his son, while he yet lived, eastward, to the land of the east.”

He did what? OMG! Childless for 100 years he then decides to get remarried and have six more children over the next number of years? And he does what with them? Let’s correct the record: he was taka 100 years old when Yitzchok was born but childless only until the age of 86 before Yishmoel was born to him and Hogor whom Soro and he later expelled for good. That said, following the trauma of nearly losing Yitzchok to the akeydo, logic would dictate that he stays very close to his new kinderlach, ober, he does what? He sends all six of his new kids -those born in the last years of his life- away? Was Avrohom mamish heartless? What was he thinking? And his wife? Did the RBSO tell him or her to send them away? How did his new wife feel about his actions? Did she protest? What’s happening here? Were we not taught to act and follow in the ways of our forefathers? We were! Is this the behavior we are to emulate? Oy vey! Who is this Ketura woman he married? What special charms did she possess that got Avrohom to begin a new life with her?

Shoin, let us begin by answering that last question first? Says Rashi that Keturah is Hogor and that the Heylige Toirah calls her by a new name. We will get to why, later. Says the Ramban that it’s taka the case that Avrohom married Hogor but adds this: Avrohom didn’t remarry until after Soro’s death, showing loyalty to her in life. Ober, once Soro was dead and buried, he was free to make peace with Hogor. He brings her back — perhaps even at Yitzchok’s urging; we shall address this possibility shortly. Ober, the Ibn Ezra disagrees and says that Keturah is a new person, a brand-new character and not Hogor. Do we need her DNA and Jerry Springer to get this all sorted out? And his rationale? “If the Heylige Toirah meant Hogor, it would say so.” Shoin, that’s logical. He adds this: The names and list of sons suggest a separate episode. He sees it simply as Avrohom’s natural vitality: “Ki chazak hoyo” —Avrohom was still full of life and blessing, (and also virility), fulfilling the RBSO’s promise to multiply his seed. Did Avrohom, still young at heart, efsher attend a singles weekend or maybe swipe right and shoin? He fell in love and before he knew what hit him, was suddenly the father of six new kinderlach?

The Sforno sees this entire episode as an expression of Avrohom’s human side; even a tzaddik has natural affection and companionship needs. Isn’t that the truth? Ober, he also says this regarding the six new entrants into the household: Spiritually, this line represents a secondary branch of humanity while Yitzchok remains the covenantal heir. More on that some other time. And the Kli Yokor adds some color with this: “Avrohom took her not from desire, but to fulfill the RBSO’s promise that he would father many nations.” In other words, it was not about the romance; it was shlichus, his mission. Of course, we can relate to this pshat because just last week in Parshas Vayero we read how Loit’s daughters -efsher thinking that there were no men left alive following the fires of Sedoim- also saw it as their mission to repopulate the world and took turns bedding their father who shared his emissions with them. And that is why raboyseyee and ladies, we must all love medrish, where -if they like you- they will get you out of any jam you might find yourself in- better than any lawyer can. Free too! They decided that Loit’s daughters were holy people and their actions 100% acceptable to them and the RBSO. But when and where the medrish decides one is a bad actor, fuhgeddaboudit. One can be innocent mamish but the medrish will paint that person with very ugly brushes. They did not like Loit very much. Though the girls mamish raped him while intoxicated, they call him the chazir. Shoin!

Ober raboyseyee, did you read the pisukim above? Seemingly not, because had you, you’d be up in arms right now and asking this question: How many concubines did Avrohom have? Though the heylige Toirah just told us that he took a new wife by the name of Keturah (or whomever she really was), you mamish missed this posik and let us reread it:

וְלִבְנֵי הַפִּילַגְשִׁים אֲשֶׁר לְאַבְרָהָם נָתַן אַבְרָהָם מַתָּנֹת וַיְשַׁלְּחֵם מֵעַל יִצְחָק בְּנוֹ בְּעוֹדֶנּוּ חַי קֵדְמָה אֶל־אֶרֶץ קֶדֶם׃

“But to the sons of the concubines that Avrohom had, Avrohom gave gifts, and sent them away from Yitzchok his son, while he yet lived, eastward, to the land of the east.”

What is going on here? How many concubines did Avrohom take for himself at the age of 140? And how many wives? Or, did he have them all along while married to Soro? Was Keturah a wife, or a concubine? Both? Help! Let’s dig veyter, but what do we know? Notice the plural — הַפִּילַגְשִׁים, concubines as in more than one — even though only one woman, Keturah, is mentioned by name. What’s going on, what’s pshat here? Nu, of course the heylige Ois was not the first to notice the wording and avada we all agree that the RBSO knew just what He was having written. Oib azoy (that being the case) what went down here? Not to worry because our Sages were all over this.

Says Rashi (Bereishis 25:6): “פילגשים — היא קטורה, היא הגר.” “The concubines — this refers to Keturah, who is Hogor.” Rashi says the plural is stylistic only. The heylige Toirah sometimes uses a plural to indicate importance or category. In other words: Avrohom had only one concubine (Hogor/Keturah), but the Toirah speaks in the plural form. Not fully satisfied with this pshat? Let’s try another flavor. The very logical Ibn Ezra mamish disagrees and says this: The plural means what it says. Avrohom had more than one concubine. He writes this: “Perhaps Avrohom had other concubines besides Keturah, though they are not mentioned by name.” And taka, so it would appear from the posik we read above. According to him, yes — it’s shayich (quite possible) there were additional women and additional children, whose stories the heylige Toirah does not record because they were not relevant to the covenantal line through Yitzchok. Gishmak and keeping it real!

And the Ramban says this: “Keturah” was one of the concubines, but the term “pilagshim” is plural because she represents the class of concubines, just as a king might say “my wives” even if he’s referring to one specific queen at the moment. And for good measure, since you’re mamish so curious about Avrohom’s virility at age 140, the Radak and Sforno say this: Keturah was indeed a concubine, even if she had the status of a wife. Seemingly, she was both! The term “pilagshim” covers all non-primary wives — so “the sons of the concubines” refers to the six sons of Keturah collectively. In other words, the posik isn’t hinting at new concubines or hidden children; it’s just a grammatical plural covering all her sons. The bottom line on this shtikel controversy is this: The heylige Toirah calls them ‘sons of the concubines’ — plural — even though only one name, Keturah, appears. Were there more? Ver veyst? Were there others he didn’t tell Soro about? Possible! Why not? Was Avrohom quietly maintaining a harem at 140? Or efsher earlier? Not likely. Our Sages step in to clean up the mess in aisle 5. Rashi says it’s just Keturah, singular. Ibn Ezra, more realistic (or nosy), thinks there were others. Ramban smooths it over — Keturah represents the class of concubines. Either way, the posik subtly reminds us that the Av of chesed was also a man of passion and vitality. Holy, yes — but also very human. He had needs. The plural keeps him human.” He had money and power; seemingly he may have also had a bunch of concubines. He was the man!

But let’s get back to Avrohom’s actions; it’s mamish shver to chap what appears to be a coldness in him. What father sends all his kids away? Avada we can chap that many a father might have issues with one or even two kids; they become prodigal children, and at times, the father taka would not mind if they left. Perhaps he would even send one away. But all six new kids? Were they all bad? How old were these kids when he sent them packing? He was 140 when he married and he died at 175. It must have taken him a few years to sire six new kids; were they but kids when sent off? Were these kids not experiencing Yishmoel’s life all over again? Was this not Yishmoel 2.0? What do our distinguished rabbis teach us on this subject?

And before we address these questions, let’s dig deeper into this: If the heylige Toirah calls her “Keturah,” and taka it does, why on earth did Chazal (our holy sages) insist it was Hogor — a woman we already said goodbye to chapters ago? Why bring her back? If the RBSO wanted us to know it was Hogor, He could have just said so. So why this midrashic “retcon?” Shoin, I see I lost you with that big word, let me explain: Retcon (verb): to alter previously established facts in a story, usually by adding new information that reinterprets what happened earlier. Need we say more? The medrish wrote the book on this.

Shoin, let’s peel this onion layer by layer: text, Rashi, medrish, and see what’s really going on beneath the surface. Are we dealing with two women, or one? The heylige Toirah says plainly “And Avrohom took another wife, and her name was Keturah.” (Bereishis 25:1) “וַיֹּסֶף אַבְרָהָם וַיִּקַּח אִשָּׁה וּשְׁמָהּ קְטוּרָה”

That’s simple enough. Another wife. New name. End of story and veyter gigangin. But our sages don’t leave this story alone and famously say (Bereishis Rabbah 61:4, Rashi ad loc) azoy: הִיא הָגָר. וְנִקְרְאָה קְטוּרָה שֶׁנִּקְשְׁרוּ מַעֲשֶׂיהָ כְּקְטֹרֶת. “She is Hogor. She was called Keturah because her deeds were as pleasant as incense.” So — same woman, new name, new chapter. Seemingly also smelled better. Ober, why did they want her to be Hogor? Let’s find out: We can kler (speculate) that our sages disliked leaving critical biblical figures with open wounds. The story of Hogor and Yishmoel — a woman exiled into the desert with her son crying under a bush — is mamish tragic. So, to give us readers a better experience, they reunited her with Avrohom as a kind of spiritual happy ending. This way, Avrohom, after losing Soro, does not die alone. He reconciles, remarries, and reclaims what was once broken.

It’s narrative teshuvah. In this view, our sages weren’t rewriting, they were redeeming, tying up loose ends. The story feels good, certainly a whole lot better than without her return. Alternatively, they might have wanted to teach that teshuvah works. Hogor, the foreign servant, the discarded “other woman” repented and became righteous. Repented for what? We were taught that she acted with haughtiness and arrogance once she became pregnant and Soro was not a happy camper. So they renamed her Keturah — from ketoires, the sacred incense — symbolizing spiritual transformation. In other words, they turned a figure of failure into one of redemption and that raboyseyee is a core rabbinic move: elevate, not erase. As well, if Keturah is a new woman, then Avrohom starts a new family entirely after Soro — one disconnected from the promise and covenant.

But if she’s Hogor, then we’re looking back: Avrohom’s life comes full circle. Every loose end is tied. Ready for Hollywood. Yishmoel’s mother returns. Yishmoel himself reappears to help bury Avrohom and symbolically, the family is healed before Avrohom’s death. The end!

That being said, does everyone agree? What about the “plain pshat” that she was taka a new person by the name of Keturah? And taka, says the Rashbam, that we must be true to form. The new wife was “אשה אחרת היתה, לא הגר.” “She was another woman, not Hogor.” As mentioned above, the Ibn Ezra sees Keturah as new, not a recycled character. He argues that the heylige Toirah would have said “וַיֹּסֶף אַבְרָהָם וַיִּקַּח אֶת־הָגָר” if it meant her. The bottom line: In the eyes of these two exegetes, Chazal’s view is a homiletic flourish — meaningful but not literal. And for those who take every medrish literally, too bad. If the RBSO wanted us to think she was Hogor, He would have said so. Were our Sages trying to rewrite pshat? Were they reading Avrohom’s neshomo, not his résumé? They saw his remarriage not as a new romantic adventure, but as part of a lifelong pattern of chesed, forgiveness, and unfinished emotional business. By making Keturah = Hogor, they framed Avrohom’s last years as the completion of his story — tying up old threads, healing old pain, and showing that righteousness includes reconciliation. Mamish gishmak.

That said, notwithstanding what the RBSO told us in His Toirah, a few exegetes couldn’t resist and said ‘No, no, that’s Hogor! The old flame!’ Apparently, Avrohom was the first guy in history to remarry his ex — with rabbinic approval. Why? Maybe because our sages couldn’t stomach the thought of holy Avrohom dying with unresolved ex issues. They needed closure. They needed a reunion episode. The Heylige Toirah gave him a second act; the rabbis gave him redemption. Shoin, whomever she was, how did she feel when he sent her new kids away? Did she argue, bite her tongue? Cry? Wonder if she was reliving the same heartbreak? Maybe that’s why her name changed. She wasn’t just Hogor anymore — she was Keturah. She’d learned to bind her emotions like incense, to rise sweetly even in smoke. And if Keturah is Hogor (as Rashi, the Midrash, and Zoihar all suggest), then this late-life reunion is not some romantic senior-citizen fairy tale; it’s the most awkward remarriage in the entire heylige Toirah! Let’s break it down, because the Heylige Toirah’s silence here is deafening. Such silence would normally give our sages of yore room for a gishmake human, emotionally loaded read. Ober, because what we read is almost nothing, let us imagine Hogor’s emotional rollercoaster. Decades after being expelled into the desert, with Yishmoel mamish near death but before hearing the voice of the malach promising that her son will become a great nation, she suddenly reappears – having been brought back by Yitzchok himself:

“וַיָּבֹא יִצְחָק מִבּוֹא בְּאֵר לַחַי רֹאִי” – “And Yitzchok came from the way of Be’er Lachai Ro’i.” (Bereishis 24:62). What’s this? Says the medrish (Bereishis Rabbah 60:14) azoy: “הלך יצחק להביא את הגר לאברהם אביו” “Yitzchok went to bring Hogor back to his father Avrohom.”

Yitzchok, efsher feeling badly that his father was alone -and lonely- went to find Hogor to bring her back; wow! Or, he might have felt for her plight; how she was kicked to the curb. Let us think about that scene through her eyes: Hogor is now much older when she walks back into Avrohom’s tent — the same tent from which she was banished years before — not as a rival, but as a penitent. This is her teshuvah arc, her redemption moment. And then… she gives birth to six sons. Six! All is good.

“וַתֵּלֶד לוֹ אֶת זִמְרָן וְאֶת יָקְשָׁן וְאֶת מְדָן וְאֶת מִדְיָן וְאֶת יִשְׁבָּק וְאֶת שׁוּחַ.” “And she bore him Zimran, and Yokshon, and Medan, and Midian, and Yishbok, and Shuach.” Six new lives. A second chance. A family reborn. And then, just like that -one posik later- “וַיְשַׁלְּחֵם מֵעַל יִצְחָק בְּנוֹ” — “He sent them away.” No divine command. No malach. No crisis. Seemingly, her husband, unilaterally, just sent them away. The bottom line: if Keturah is Hogor, and even if not, this must have been devastating. Shreklich! Though our sages take many liberties- license- mamish- when the Heylige Toirah is silent, and mamish fill in the lacunas with different possibilities which many believe are all true- for some reason, in the case where the father sends away his six kids born to him in the last years of his life, Chazal don’t give us her words; crickets! She is speechless. What’s pshat? Such silence zicher invites midrashic imagination. What was Ketura (aka Hogor!) thinking and feeling when Avrohom sent her sons away? If we dig carefully, there’s plenty between the lines. Let us then imagine Hogor’s thoughts; who’s going to prove the heylige Ois wrong?

*“All those years I told myself Avrohom loved me — that he only sent me away because Soro insisted. I waited, I wept, I believed. And when Soro was gone, Yitzchok himself came for me — her son, not mine. I thought maybe it was all meant to be, bashert mamish. And then, just when my children laughed and played and called him Tatty … he sent them away too?! No malach this time. No promises. Just gifts, and goodbye.”* Nebech!

What’s taka pshat here? We can mamish picture Hogor’s heartbreak; a second exile. While searching through the medrish for answers on this perplexing topic, the heylige Ois did come across a shtikel answer from the heylige Zoihar (Vayeira 133a) who softens the blow with this thought: Hogor, now Keturah, was on a higher level. She understood that Avrohom’s mission was unique to Yitzchok. She knew this from her own expulsion. Her role was to restore harmony, not to compete. In that mystical view, she agreed to the separation. She knew these sons had their own destinies, to spread fragments of truth eastward. Her heartbreak became spiritual surrender. And adds the Ois azoy: at least she had her man back. Says the medrish (Bereishis Rabbah 61:4), azoy: That’s why she’s called Keturah — from ketores, incense:

“שקשרה פתחה, שלא נזקקה לאדם מיום שפירשה מאברהם.”

“She kept herself pure from the day she separated from Avrohom.” She was closed for business, if you chap. Even in pain, she was faithful. That’s real love!

“והיא קְטוּרָה – שֶׁנִּקְשְׁרוּ מַעֲשֶׂיהָ.” “She is Ketura, for her deeds were knotted (bound) — she had remained chaste and righteous from the day she left Avrohom.” In other words, she never moved on. She stayed loyal, waiting decades for him. Imagine the emotional reunion — and then the heartbreak of watching him send her children away as well! The medrish paints her as faithful, penitent, pure — but silent. Her voice is missing. She’s erased from the narrative once again. That said, let’s check in with power players: Rashi, Radak, and Ramban, they must say something. Says Rashi only this: Avrohom gave them parting gifts. Game show losers typically get these.

And taka the Abarbanel asks outright: How could Avrohom, the man of chesed, send his sons away? His answer: it was not cruelty, but “chesed in disguise” — so they would not fight over inheritance after his death. Still, Abarbanel’s question itself is proof that he felt the tension. Malbim adds that “the children of Ketura were spiritual but not chosen” — meaning Avrohom recognized their value but had to preserve boundaries. That’s emotional and psychological conflict, not indifference.

The bottom line: If Ketura is Hogor, then this is the second time she’s having family issues because of Yitzchok. The first time, she was cast out for Yitzchok’s protection. The second time, her sons are cast out for Yitzchok’s inheritance. Same pattern. Same heartbreak. Different generation. The bottom line: Ketura/Hogor was twice banished by the same man, twice told that her children weren’t part of the covenant. Once by Soro, now by Yitzchok’s shadow. For years, she waited, she dreamed, and yet, when Avrohom sent her sons eastward, she did not protest. The woman who once wept in the desert remains dignified, silent, and loyal to her man, but alone. Nebech!

Another bottom line: Avrohom, the heylige patriarch, father of nations, the original multi-tasker, had quite the second act. Most men, after burying their wives, buy a new recliner. Avrohom? He remarries his old flame, has six more kids, and then sends them packing with a few parting gifts — maybe a gift card to the nearest yoga studio in the East. But was that chesed or heartbreak?

And while it’s taka emes that most famous authorities do not weigh in on this matter, more modern commentators (like Nechomo Leibowitz and Rav Hirsch) note how the Heylige Toirah’s male focus leaves women like Hogor/Keturah voiceless at key emotional points. In other words: make your own pshat. The Heylige Toirah doesn’t tell us what Keturah said when Avrohom packed up her sons. Maybe she cried. Maybe she understood. Maybe she smiled through tears, knowing she had finally come full circle — no longer the scorned maid, but the woman whose children would build nations.” It’s a profoundly human moment: this time around there’s no jealousy, no divine punishment, no screams in the desert — just quiet dignity.

Ober the real bottom line may be more about holy men and their complicated marriages. “If Keturah was Hogor, then OMG — this is one for the history books. The woman he once exiled, nearly left for dead, comes back for round two, has six more kids, and gets packed off again. If you pitched that as a Netflix series, they’d call it too far-fetched. But this is the Heylige Toirah — where holiness and heartbreak share a tent. Where a tzaddik can send his wife away twice and still be called ‘Avrohom ohavi’ — My beloved Avrohom (Yeshayahu 41:8). Maybe that’s the point: Avrohom wasn’t perfect. He was complicated. And maybe – the Ois is thinking out loud- that’s why the RBSO loved him: not because he always got it right, but because he always kept moving forward, even through his own contradictions.” That’s mamish deep and many can relate.

The final bottom lines of this union: The Heylige Toirah never told us why Avrohom got remarried. And it certainly didn’t tell us that he remarried Hogor. Farkeret: it does tell us that he married a new shiksa by the name of Ketura and together, they sired six new goyim who were expelled but given money and gifts to rebuilt their lives elsewhere. The children from Keturah were “spiritual offshoots,” carriers of kochos that would later be spread among the nations. What all that means is for another day.

A gittin Shabbis!

The Heylige Oisvorfer Ruv

Yitz Grossman