SPECIAL EDITION

PRE YOM KIPPUR AND THE OIS’S ANNUAL MICHILA FORGIVENESS FORM

The Tishrei Beard:

Raboyseyee and Ladies,

According to informed sources on the heylige Internet, here are the top five reasons people grow beards:

1- Fashion & Aesthetics

- Identity & Expression

- Convenience / Low Maintenance:

- Social & Cultural Trends:

- Covering or Camouflage:

Nice but did you ever hear about the Tishrei Beard? What the hec is a Tishrei Beard you ask? Never heard of this concept? There was a time when the Tishrei Beard was a condition precedent to leading the davening during the High Holy Days. Tishrei beards carry symbolism, tradition, and communal meaning. As well, the person leading the davening needed to be married. We shall cover this topic below but begin with this:

A few weeks ago, a piece I wrote about the change we have seen in Selichos over the years was well received. How well? So well that even my neighbor Ben Heller, who happens to sport a shtikel beard all year round and takes every opportunity to rib me, admitted with a full throat that it was an excellent post. So he signaled when he flashed both open hands from across the room and so he stated. A few days later I heard from his amazing eishes chayil who also enjoyed the piece. And why am I sharing this information and naming names? Because his beard and rare compliment inspired me to take a look at the role of the Yom Kippur beard as well as other changes in the Yom Kippur liturgy (davening). How the entire feel of the Yom Kippur davening (service) has changed, and how those changes have made our Yom Kippur experience not just tolerable but at times, also pleasurable.

Let’s be honest: Most of us don’t know what more than half the words mean in the Yom Kippur Machzor. What to do? We skim, zone out, or daydream about anything and everything in the world. I dare say that the only thing we are not thinking much about is tshuva, saying sorry to the RBSO for yet another year of very bad behavior. By the early afternoon many are thinking about the menu for break-fast and the women are contemplating when to start defrosting the bagels and when to take other items out of the fridge.

As we harken back to Yom Kippurs growing up, most of us picture the bearded chazan standing at the bimah, eyes closed, voice soaring through the shul, and the tzibur (congregation) barely daring to breathe—so intimidated were we by the sheer gravity of it all. The chazan was all decked out in white to match the tablecloths and all else in the room including most yarmulkas. Together with the white kittels almost all men donned just under their talaysim -some had matching white ties- the entire room looked eerily sterile. The mood was palpable.

But the Yom Kippur chazan of 200 and even 50 years ago is almost unrecognizable compared to the modern maestro guiding us through soulful nigunim today. Let’s take a scroll through history, because trust me, the journey from beard to nigun is quite dramatic.

Once upon a time, the Yom Kippur chazan did all the work; he sang and the people alternated between standing and sitting at the appropriate times of which there are many. Sporadically we followed the machzor, for sure we napped, maybe we thought about that Aveiro(s) we enjoyed and wouldn’t mind trying again after the fast. We had nowhere to go and if the chazan schlepped out the davening, hec, if was quite ok. He was the holy one in the room. In fact, many orthodox communities went out of their way to hire the right High Holy Days Chazan. And by right, he needed to also look right. What’s pshat? The Yom Kippur chazan needed to be married, and for sure he needed a beard. How those things qualified him to help atone for our sins -or even his own- ver veyst? Is forgiveness that simple? Gishmak!

Back in the 18th and 19th centuries, a Yom Kippur chazan was a figure of awe, mostly because of the beard. I’m talking a full beard, one that could easily house a small family of sparrows. The beard wasn’t just for warmth or vanity—it was a badge of piety, maturity, gravitas, and authority. Beards have long symbolized wisdom, authority, and manhood. Rabbis, Chassidim, even kings of old, proudly sported them. Today, hipsters reclaimed the beard; a perfectly groomed beard can now make a man look like he’s starring in a Gemora commercial. As well, beards cover weak chins, acne scars, or double chins. They’re practical: warm in winter, shield in summer. And shaving? Many cannot stand it. The bottom line: A beard is like a Swiss Army knife: conceals sins, protects from the cold, looks pious. In years past, if you showed up without a full beard, you might as well have been a boy playing at grown-up prayers; the congregation might politely listen, but internally they were judging your lack of whisker-based gravitas. If you think the Ois has lost his mind, maybe so, ober it’s taka emes, and let’s check out the Shulchan Aruch (Orach Chaim 53:6) which states this:

“One is not to appoint an individual as the set chazzan for the community unless he has a beard, due to honor of the kehal (congregation).”

And this: The Shulchan Aruch (Orach Chaim 53:4) mentions that a shaliach tzibur (prayer leader) should ideally be “raui” — fitting — which includes being free of major sins, having a good reputation, and being accepted by the congregation. And while it doesn’t explicitly require him to be married, the Mishna Berura (53:27), brings the custom that on the Yomim Noraim it is preferable that the shaliach tzibur be married. Why? Because a married man is seen as more settled, responsible, and serious. In the words of the heylige Gemora (Yevamos 63a), אָמַר רַבִּי תַּנְחוּם אָמַר רַבִּי חֲנִילַּאי:

כָּל אָדָם שֶׁאֵין לוֹ אִשָּׁה — שָׁרוי בְּלֹא שִׂמְחָה, בְּלֹא בְּרָכָה, בְּלֹא טוֹבָה.

וְאָמְרִי לָהּ: בְּלֹא תּוֹרָה, בְּלֹא חוֹמָה.

וְאָמַר רַבִּי תַּנְחוּם בַּר חֲנִילַּאי: כָּל אָדָם שֶׁאֵין לוֹ אִשָּׁה — אֵינוֹ אָדָם שָׁלֵם.

In English: Rabbi Tanchum said in the name of Rabbi Chanilai:

Any man who has no wife lives without joy, without blessing, without goodness.

Some say: without Torah and without a protective wall.

And Rabbi Tanchum bar Chanilai said: Any man who has no wife is not a complete man.

A man without a wife is not fully complete? They did forget to tell us that once married, that same man is finished, over and done!

And it’s taka emes: Many kehillos would not allow a young, unmarried man to daven on Rosh Hashono or Yom Kippur. They wanted someone “seasoned” with life experience and the humility that comes from marriage and responsibility. It’s taka emes that marriage humbles the man, oy vey!

Let’s review what was: while the beard was not and is not an explicit halacha, it was certainly a widespread minhag and symbol of dignity. On the other hand, being married had more teeth than the beard for the Yomim Noraim and many poskim and minhagim preferred/required the chazan to be married, to ensure a sense of gravitas and “shalem” status. And that’s why back in the shtetl days, a 19-year-old bachelor with a golden voice might be welcome to lead Shabbos Musaf, but come Yom Kippur, forget it! Without a wife (and maybe a beard), he wasn’t stepping up to the amud.

The bottom line: In many Ashkenazic communities, particularly in Eastern Europe and Israel, there was a strong tradition that the chazan should have a full beard, at least during the month of Tishrei which features the High Holy Days. This practice was deeply ingrained and often considered a prerequisite for leading the Yom Kippur services. While this was not always codified in law, it was a widely accepted minhag Yisroel (custom) that underscored the chazan’s maturity and spiritual stature. The bearded chazan was the superstar and Yom Kippur was his stage. People didn’t come to sing; they came to watch. Every note was dramatic, every pause suspenseful, The congregation? Mostly silently davening that he would finish timely and certainly before they fainted from starvation. Participation was minimal. The shtetl’s chazan didn’t need an audience — he needed worshippers who could sit quietly in awe. In those days, the chazan was the vessel through which the congregation experienced Yom Kippur. You could feel the weight of every sigh, every note, and every pause. The role demanded a perfect blend of physical maturity, spiritual intensity, and vocal stamina. And of course, also the beard!

And the voice! Oh, the voice had to be strong enough to carry from one end of a cavernous wooden shul to the other, over the coughs, those sneezing and blowing their noses incessantly. The chazan sang almost entirely alone, leading Kol Nidri, Musif, Neilah, and every long, winding piyut in between. The tzibur sat with heads bowed, murmuring omen only when absolutely required. Back in the day, the bearded chazan was the main man. He conducted the spiritual orchestra, carried the weight of each selichah and piut; he held the congregation’s heart in his voice. People came for the gravity, the mastery, the majesty.

Ober, as Jewish life moved from shtetl to city, as synagogues expanded in size, and as communities in America grew, a new challenge appeared: a single voice, no matter how strong, couldn’t always reach the back rows. As a result, early in the 20th century, cracks in the beard paradigm. Chazonim began incorporating regional styles, maqams, and motifs, partly to enliven the davening and partly to keep everyone awake during long stretches of the avoida that few followed. Congregants started joining in on repeated refrains. It was subtle but it was the start of something revolutionary: communal engagement. The beard was still respected, but already in urban centers, the focus subtly shifted. It was no longer enough to just look wise; you had to sing wisely, too.

The seismic shift, a revolution mamish wrapped in melody came with the emergence of Shlomo Carlebach, OBM, who changed everything. Where once the chazan towered alone, now the congregation could participate, sing along, and feel the davening in their bones. The music became not just a vehicle for the chazan but a bridge to d’veikus (connectivity long before that word had real meaning), that sweet, meditative connection to the RBSO.

Some shuls started incorporating harmonized choirs, often singing counter-melodies to Carlebach-inspired tunes or other nigunim. Suddenly, the davening felt alive, not just a recital of ancient words. At the same time, though Carlebach was bearded, appearance became secondary to authenticity and connection. You could have a clean-shaven chazan with a golden voice and still command the hearts of the congregation. Didn’t we love the beardless Neil Diamond as the chazan leading Kol Nidrei in the Jazz Singer? We sure did! The people no longer listened silently. They sang. They hummed. They shokeled (swayed). And, yes, they sometimes whispered the words because they didn’t fully know them—but somehow, it didn’t matter. This period marked the transition from solitary awe to communal soulfulness. Yom Kippur became less about trembling before the authority of the chazan and more about experiencing the davening as a living, breathing melody. The beard lost its authority. Yet, even today in our times, in certain shuls, you know it’s Tishrei when you walk into shul and see a few suddenly-bearded men. It’s likely the case that they are leading at least one of the tifilos. And that raboyseyee is the shift in a nutshell. Even as late as the 1960s, the chazan was judged on beard length, marital status, and whether he could stand for 12 hours without fainting. He was the baal tefillah, the spiritual captain of the ship, and his voice carried everyone through the day.

Ober, do we in 2025 really care what the chazan looks like? Does it bother you that he may be single or divorced? A nechtiger tug (fuhgeddaboudit). The chazan’s role has transformed. It’s no longer just about mystical nusach or the length of his whiskers. Now it’s about the sing-along kumzitz: the winning chazan knows to pick soulful tunes, happy tunes, songs that lift spirits, and make everyone — from the youngest bochur to the seasoned godol feel connected. Beards still carry some gravitas, but connection and joy are the true measure of a chazan’s success. The chazan might have the longest, most mystical beard in the world, but if his song selection makes people check their watches constantly, he might as well be invisible; you will surely not see him next year. In today’s times, a chazan without a sing-along is like a beard without a face — present, but missing the point.

Today, nobody’s checking his beard or asking about his wife. Today’s top five qualifications include these:

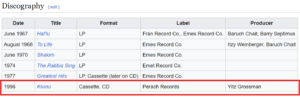

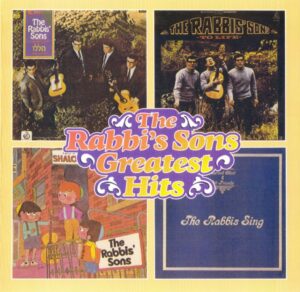

- The playlist. Does he know which niggunim will stir the soul, and when to bring them in? is he familiar with the Rabbi’s Sons and Devikus albums. Givaldig! Side: a bunch of years back, the heylige Ois produced the Rabbi’s Sons last album.

- Soulful moments. He has to know when to drop in a slow, heartfelt Carlebach niggun to make the whole shul shokel in place.

- Uplifting bursts. He must know how to shift gears — from the “crying at Neilah” mode to the “dancing inside your seat” mode of a fast Eitan Katz or Dveikus melody.

- It’s not about him singing anymore — it’s about him getting everyone else to sing along. If the kahal isn’t humming, clapping, or at least swaying, he failed.

- From Carlebach’s timeless nusach, to the Rabbi’s Sons and Eitan Katz’s soulful twists, to Abe Rottenberg’s classics, to the Deveikus slow burners, and to newcomers like Ishay Ribo, he has to weave them into a tapestry that makes Yom Kippur come alive.

As an aside, though the words of Oichiolo LoKel were written by Rav Avraham Ibn Ezra in the 12th century, it took until the 21st century for a gifted musician by the name of Isahy Ribo to come along and popularize a haunting, obscure piyyut in the machzor which has suddenly become the go-to Yom Kippur niggun, which has spread like wildfire through shuls, kumzitzim, and especially Yomim Nora’im tefillos. Such it the power of a melody: it inspires us to sing along and to shokel as well. Listen to it here: https://music.youtube.com/watch?v=rNOaPRA8Wew

The final bottom line: The Tishrei beard had given way to the Tishrei DJ. The modern chazan is more spiritual DJ than he is a soloist. He sets the mood, cues the music, and makes sure every person in shul feels like they’re not just listening, but participating. A good Baal Tifilla is one whose song selection is curated with soulful and even happy melodies when called for, and one who makes us feel mamish connected. He elevates our Yom Kippur davening, and avada helps the day go by while keeping us engaged and motivated. We all connect and shokel better through familiar melodies. It’s a win win; for us and for the RBSO.

And now, with Yom Kippur mamish looming, the heylige Ois is back with his annual michila (forgiveness form).

🕊 PRE-YOM KIPPUR OFFICIAL MICHILA FORM 🕊

For all guilty parties, big and small

(Because a simple “sorry” just won’t cut it this year.)

WHO SHOULD USE THIS FORM?

☑ Speakers, facilitators, and participants of loshoin horo or richilus.

☑ Listeners who secretly enjoyed the gossip.

☑ Anyone who upset a friend, spouse, relative, or colleague this past year (intentionally or not).

⚠ Warning: Half-truths, exaggerations, or outright lies “I didn’t really forward that email” will void this form in the eyes of the RBSO.

SINNER INFORMATION (YOU!)

1️⃣ Name: __________________________________

2️⃣ Cell #: __________________________________

3️⃣ Email(s) used to bad-mouth others (list all):

FORGIVENESS REQUESTED FROM

4️⃣ Name & Email of Person(s) You Offended:

To: ____________________________

(Use a new form for each recipient. Extra sheets allowed.)

SPECIFIC SINS / CONFESSIONS

5️⃣ What I Specifically Said or Wrote:

(Attach copies of emails, text messages, forwards, etc.)

5 Optional Financial / Mischief Confession:

(Describe lies told to creditors, unpaid debts, or other “creative adventures”)

Types of Sin Committed (check all that apply):

☐ Loshoin Horo

☐ Richilus

☐ Exaggerated stories

☐ Other: __________________________

Frequency (check one or more):

☐ 1–5 times

☐ 6–10 times

☐ Weekly

☐ Whenever opportunity presented

☐ Whenever your name came up in conversation

☐ Daily… while brushing my teeth

☐ Multiple times in my dreams

THE APOLOGY STATEMENT

I am truly sorry!

Additional Note to Those Offended:

We are in this together. I admit my guilt as a conduit for others, forwarding schmutz I dug up, and while I may have enjoyed it at your expense, I beseech you to offer me michila so the RBSO will go easy on me.

Mutual Accountability Clause:

Why forgive me? Because you probably did the same. Don’t walk around like a victim. If you refuse, you are a hypocrite — and yes, I will badmouth you all over again and tell everyone on my email list.

I am willing to forgive you if you forgive me. Shoin!

SIGNATURES

Signature of Sinner: ________________________

Date: ________________________

FINAL REMINDER

By completing this form, you have officially confessed, admitted, apologized, and participated in a pre-Yom Kippur cleansing ritual more effective than flowers, jewelry, or sweets.

Tip: Keep this form handy — it can also be used when you offend people during the year.

Wishing all my readers the very best for the coming year. A Gemar Chasima Toiva!

The Heylige Oisvorfer Ruv

Yitz Grossman