Miketz 2020 – The Vicissitudes of Life

by devadmin | December 18, 2020 12:56 am

Raboyseyee and Ladies,

Raboyseyee and Ladies,

With great pleasure, we begin with a big mazel tov shout to Isaac Rosen upon his forthcoming marriage -this coming Sunday- to Emily Klein. We –Lisa and I- have had the great pleasure of hosting Isaac in our home for many years -kimat since birth- watched him blossom into the man he is today, and Isaac is our son Jonathan’s very closest friend. He is the amazing son of long-time friends -decades mamish- of Malki and Phil Rosen, and grandson of Sara and Moishe, OBM, Leifer, also friends of many decades. A big mazel to you Isaac and to your beautiful wife to be, Emily. May you and she build a big beautiful house together (Lawrence ok), and bring your parents and the entire extended Klein/Rosen and Leifer families much joy and nachas. Go Isaac!

“The Vicissitudes of Life”

According to at least one definition of the phrase, it’s meant to convey the following: to survive the vicissitudes of life is thus to survive life’s ups and downs, with special emphasis on the downs.

And that raboyseyee, is a summary of Yoisef’s life; his highs, lows, and highs again as described in the heylige Toirah last week, this week, and next. Yoisef experiences them all. And if the RBSO featured Yoisef in four different parshas, the least we can do is take a second look. We’re back with more on Yoisef, ober surprisingly, this week, we will be asking a few tough questions on some of his own behavior.

Shoin, to chap what’s on the Ois’s mind this week and last night as he was flying back from sunny and warm Miami into a snowstorm, and as Chanukah comes to an end, we need to go back one parsha and chazir -bikitzur mamish (in short)- the saga of Yoisef. For years, the heylige Ois has been asking why the brothers who plotted to murder one of their own, and took concrete actions in furtherance of the conspiracy, are referred to a “Shivtei Ko,” the RBSO’s holy tribes. Their names were selected by the RBSO Himself to adorn the breastplate of the Koihen Godol when entering the inner Temple to perform his service. How could they have gotten away with such gross wrongdoing and yet be forgiven by the RBSO? Did they ever truly apologize to Yoisef’s face for their nefarious plan which they almost succeeded in carrying out? And did they say they were sorry to the RBSO? Is kidnapping, attempted murder, a cover-up which included lying to their father, acceptable behavior? As an aside, nowhere do we read how their mother’s felt. Did they not have feelings? Were they all dead at this point in time? Ver veyst?

Shoin, to chap what’s on the Ois’s mind this week and last night as he was flying back from sunny and warm Miami into a snowstorm, and as Chanukah comes to an end, we need to go back one parsha and chazir -bikitzur mamish (in short)- the saga of Yoisef. For years, the heylige Ois has been asking why the brothers who plotted to murder one of their own, and took concrete actions in furtherance of the conspiracy, are referred to a “Shivtei Ko,” the RBSO’s holy tribes. Their names were selected by the RBSO Himself to adorn the breastplate of the Koihen Godol when entering the inner Temple to perform his service. How could they have gotten away with such gross wrongdoing and yet be forgiven by the RBSO? Did they ever truly apologize to Yoisef’s face for their nefarious plan which they almost succeeded in carrying out? And did they say they were sorry to the RBSO? Is kidnapping, attempted murder, a cover-up which included lying to their father, acceptable behavior? As an aside, nowhere do we read how their mother’s felt. Did they not have feelings? Were they all dead at this point in time? Ver veyst?

For reasons that seemingly don’t concern us, the RBSO decided to leave those factoids out of the script, ober the bottom line is azoy: many a sage has spilled ink trying valiantly to cover-up the bad, or at least questionable behavior of the brothers. Why? Because if the RBSO seemed to have moved on and allowed the Yiddin, as a nation, to sprout forth from them, all was good in the Yaakov Ovenu household, and therefore looking back, their actions must have been kosher from the get go. Ober, is that emes? The bottom line is that their actions were not normative behavior and don’t try this at home if you’re felling pangs of jealousy. Our sages have proffered various ideas in their attempts to justify their actions and they have done quite the job. Ober, did Yoisef himself have clean hands? Did his behavior, as delineated in great detail in this week’s parsha, not in many ways mimic theirs? Was he seeking revenge? Did he ‘do unto them’ as they had ‘done onto him’? Did he needlessly prolong his father’s suffering? Did he intentionally torment his brothers? Would his brothers not have instantly recognized the folly of their ways had he only and instantly identified himself? Was there really a need to punish them and by extension his father? To arrest them, to hold them, to paly mind games? We shall shine a shtikel light on the interactions between Yoisef and his brothers and ask why he is referred to as Yoisef Hatzadik (Joseph the righteous) when his behavior -at least for a period of time- may have been just as questionable.

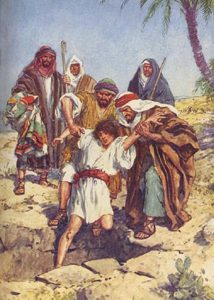

Last week: as Parshas Vayeshev began, we learned -from the text itself- that Yoisef was Yaakov’s favorite son. His dad knitted him a multicolored tunic to express his love. Ober the rest of the parsha is dedicated -save one other yeridah (fall from grace) of Yehudah as he got entangled sexually with Tamar- to Yoisef’s incredible descent. He went from the loftiest heights to the lowliest depths, from favorite and beloved son born in his father’s old age, to a hated and persecuted brother who was thrown into a pit with the intention of letting him die there. What could be worse? And it all happened in a matter of weeks or months. And if being left in a pit to die wasn’t enough, he was then sold into slavery for a few silver coins. And if that weren’t enough, accused of sexual impropriety (attempted rape), Yoisef’s fall wasn’t quite over; the hits kept coming and he found himself in an Egyptian prison. Here was this Jewish salve -decades before any other Jew stepped into Egypt- and Yoisef shared his quarters among people not very inclined to befriend him. Very pleasant, his conditions could not have been. Yikes! We can imagine that the Egyptian jail was not a sleepaway camp, if you chap. This was real. In fact, aside from a few tidbits of good news -to include that his employer Mr. Potiphar liked him (according to one medrish, he desired Yoisef for homosexual activities), that his jailer also loved and trusted him, and that the RBSO was with him while incarcerated, as the parsha came to an end, Yoisef was already in prison for a decade or close to 12 years as we shall read below. Nebech. What could be worse? Shoin, we forgot to mention his last disappointment which according to some, led to a two-year extension of imprisonment. Just when he thought he might get help from the Saar Hamashkim (chief wine butler) whose dream Yoisef correctly interpreted, and of whom Yoisef asked for a shtikel favor, Yoisef was again disappointed when the gentleman he helped had forsaken him.

Last week: as Parshas Vayeshev began, we learned -from the text itself- that Yoisef was Yaakov’s favorite son. His dad knitted him a multicolored tunic to express his love. Ober the rest of the parsha is dedicated -save one other yeridah (fall from grace) of Yehudah as he got entangled sexually with Tamar- to Yoisef’s incredible descent. He went from the loftiest heights to the lowliest depths, from favorite and beloved son born in his father’s old age, to a hated and persecuted brother who was thrown into a pit with the intention of letting him die there. What could be worse? And it all happened in a matter of weeks or months. And if being left in a pit to die wasn’t enough, he was then sold into slavery for a few silver coins. And if that weren’t enough, accused of sexual impropriety (attempted rape), Yoisef’s fall wasn’t quite over; the hits kept coming and he found himself in an Egyptian prison. Here was this Jewish salve -decades before any other Jew stepped into Egypt- and Yoisef shared his quarters among people not very inclined to befriend him. Very pleasant, his conditions could not have been. Yikes! We can imagine that the Egyptian jail was not a sleepaway camp, if you chap. This was real. In fact, aside from a few tidbits of good news -to include that his employer Mr. Potiphar liked him (according to one medrish, he desired Yoisef for homosexual activities), that his jailer also loved and trusted him, and that the RBSO was with him while incarcerated, as the parsha came to an end, Yoisef was already in prison for a decade or close to 12 years as we shall read below. Nebech. What could be worse? Shoin, we forgot to mention his last disappointment which according to some, led to a two-year extension of imprisonment. Just when he thought he might get help from the Saar Hamashkim (chief wine butler) whose dream Yoisef correctly interpreted, and of whom Yoisef asked for a shtikel favor, Yoisef was again disappointed when the gentleman he helped had forsaken him.

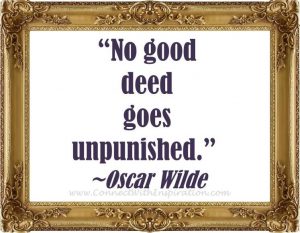

The bottom line of Vayeshev for Yoisef was azoy: early in the parsha, Yoisef was forsaken by his brothers, and as the parsha ended, the last sentence told us that Yoisef had now been forgotten and forsaken by a gentleman he did a favor for. Shoin: lesson learned. No good deed goes unpunished and if that’s not 100% emes, because every once in a while, along comes a person you did good for and shows real appreciation, sadly it’s the reality more times than not. Haven’t many of us been forgotten by those for whom we extended ourselves? We have! How many times have you lent someone money only to find that not just aren’t you being repaid, but that very friend now avoids you altogether? How many times has a person you helped crossed the street when he sees you coming? Shoin, let’s not get depressed on this last night of Chanukah and let’s instead remember Yoisef’s meteoric rise to power and what happened next.

The bottom line of Vayeshev for Yoisef was azoy: early in the parsha, Yoisef was forsaken by his brothers, and as the parsha ended, the last sentence told us that Yoisef had now been forgotten and forsaken by a gentleman he did a favor for. Shoin: lesson learned. No good deed goes unpunished and if that’s not 100% emes, because every once in a while, along comes a person you did good for and shows real appreciation, sadly it’s the reality more times than not. Haven’t many of us been forgotten by those for whom we extended ourselves? We have! How many times have you lent someone money only to find that not just aren’t you being repaid, but that very friend now avoids you altogether? How many times has a person you helped crossed the street when he sees you coming? Shoin, let’s not get depressed on this last night of Chanukah and let’s instead remember Yoisef’s meteoric rise to power and what happened next.

Welcome to Parshas Miketz, where finally, and according to Rashi and who knew better, after 12 years a slave, Yoisef is coming home. Well, not home but out. Nu, it is the season for pardons and clemencies, so says the New York Times and other media outlets, and this week we shall read of what took place following his release from prison and his appointment as viceroy of Egypt. We should avada not gloss over the miraculous resurgence of Yoisef; from prisoner to groise-macher (top dog) in Mitzrayim. Were his story not found in the heylige Toirah mamish, one would be hard pressed to believe his turnaround and comeback. Were this but a medrish -and avada all medrish is 100% emes except that some didn’t happen quite yet- one would not be out of order were one to be skeptical of the gantze myseh. Can one mamish be a captive prisoner one day and viceroy of a country under a goyishe king the next? How taka does one go from a dungeon to a most surprising rise directly to the highest seat of government? Yoisef becomes the most powerful man in Egypt; his word is law, as second to the king and as overseer of the entire country and its enormous economy. No one in Egypt raises a hand or foot without his authority. How this happens? The RBSO! Shoin and veyter. Ober the drama has more life.

In a classic case of role reversal, this week, it’s the brothers, riding high these past 20 years, who will fall from grace. As Yoisef rises, the brothers are descending precipitously. Before we get to the end of this week’s parsha, Yoisef’s ten brothers will have been arrested and held for three days, his brother Shimon will have been imprisoned on trumped up charges while Yoisef himself was also busy concocting several schemes to get his now compliant bothers to also deliver his only blood brother Binyomin whom Yoisef also puts under house arrest for a short while. OMG! It’s mamish like being a rouge leader of certain foreign countries. One day you’re the Prime Minister, or President for life, and the next, you’re either in exile, jail, or shot dead. By the end of Parshas Miketz, it’s the brothers who find themselves at a dead end, in a foreign country and in a very difficult situation, especially so when Yoisef’s goblet is discovered in Binyomin’s sack. They chap that Binyomin is not coming home with them to their father. They cannot imagine how their father, and they themselves, will survive this terrible blow. Shoin, let’s not jump ahead as the drama comes climaxes in Parshas Vayigash, incidentally the heylige Ois’s bar mitzvah parsha.

In a classic case of role reversal, this week, it’s the brothers, riding high these past 20 years, who will fall from grace. As Yoisef rises, the brothers are descending precipitously. Before we get to the end of this week’s parsha, Yoisef’s ten brothers will have been arrested and held for three days, his brother Shimon will have been imprisoned on trumped up charges while Yoisef himself was also busy concocting several schemes to get his now compliant bothers to also deliver his only blood brother Binyomin whom Yoisef also puts under house arrest for a short while. OMG! It’s mamish like being a rouge leader of certain foreign countries. One day you’re the Prime Minister, or President for life, and the next, you’re either in exile, jail, or shot dead. By the end of Parshas Miketz, it’s the brothers who find themselves at a dead end, in a foreign country and in a very difficult situation, especially so when Yoisef’s goblet is discovered in Binyomin’s sack. They chap that Binyomin is not coming home with them to their father. They cannot imagine how their father, and they themselves, will survive this terrible blow. Shoin, let’s not jump ahead as the drama comes climaxes in Parshas Vayigash, incidentally the heylige Ois’s bar mitzvah parsha.

We should avada not forget to mention the pain and suffering that Yaakov, the father of all the boys has been suffering. How much must one father endure? What was going through his mind as the brothers described their interaction with their still unidentified brother, now top dog in Mitzrayim? Oy vey? Was all this pain and suffering a prerequisite for his selection as the third of our forefathers? Is that what it took? Bereft of Yoisef for over 20 years and now he had to listen to his son’s tell him why they came back without brother Binyomin? Oy vey.

Having laid out what went down, we ask again azoy: Was Yoisef correct in exacting revenge on his brothers with all his taunting? Was Yoisef the Tzadik acting correctly while inflicting such pain on his own father? Was he doing the right thing when arresting them all, holding Shimon and then Binyomin? What excuse did Yoisef have or ever proffer for not alerting his father that he was alive and well?

Nu, the heylige Ois admits that over the many years he has been studying the Yoisef saga, he felt only rachmonis, empathy and more for Yoisef who was but an innocent victim of insane jealousy. His suffering touches the soul of all who study him; he’s everyone’s favorite and beloved Toirah character. Moishe may have led the Yiddin out of Mitzrayim, but it’s Yoisef they all love. As mentioned last week, books, plays and movies about his life remain popular as does his name. Ober this year the Ois came across a question asked by the Abrabenel (side note: the Ois’s father, OBM, studied his writings diligently over his years), who asks azoy: why did Yoisef alienate himself from his brothers and speak harshly to them? Was this not a criminal transgression on his part, being vengeful and holding a grudge? And even if they conspired to cause evil to him, the RBSO turned it for the good – so why should he seek revenge twenty years later? … And as for his elderly father, who had already suffered much upheaval and worry – how could he not have mercy upon him, and feel pain for his father’s sorrow? Taka he asks good questions.

So we ask azoy: did Yoisef have clean hands? Did his own actions not epes ring familiar? Was he, the victim of abuse, now the abuser? Was he any better than his brothers? Is revenge sanctioned in the heylige Toirah? It is not (except where the RBSO, as in the case of the Midianites, specifically so orders)! And while it’s emes that the heylige Toirah was still a few hundred years away from being revealed, are we not taught that the holy brothers, to include Yoisef, all observed it? We were! How could Yoisef act as he did? Nu, let’s try finding answers.

So we ask azoy: did Yoisef have clean hands? Did his own actions not epes ring familiar? Was he, the victim of abuse, now the abuser? Was he any better than his brothers? Is revenge sanctioned in the heylige Toirah? It is not (except where the RBSO, as in the case of the Midianites, specifically so orders)! And while it’s emes that the heylige Toirah was still a few hundred years away from being revealed, are we not taught that the holy brothers, to include Yoisef, all observed it? We were! How could Yoisef act as he did? Nu, let’s try finding answers.

Says Nechama Leibowitz that Yoisef mamish loved and longed for his brothers. Seemingly he had an unusual way of showing his love. Shoin, is arresting and causing much anxiety while locked up, and on their way home to their father, twice, the correct way to show it? What’s pshat? Ober, she says that throughout the unfolding saga Yoisef has to overcome his compassion for his brothers and has difficulty restraining himself so as not to cry. Moreover, once he did expose his identity, he did express love and affection towards them with gentle and compassionate behavior. And? From his actions, we see, says she, that he did love them but that his actions -though questionable to say the least- demonstrate that he had good intentions. Did Yoisef express his good intention? He did not! Did he tell them they’re all under arrest but for their own good because his intentions were good? Not! What were his good intentions? Ver veyst? Ober, let us recall that although he spoke harshly at times, and in an accusatory tone, he did leave them with gifts, and he did invite them to dine with him at the palace. Were any of you invited? Not! The brothers were and shoin, Yoisef has clean hands. She adds that we see, following Yaakov’s death, that Yoisef tells them that they need not fear him because he is not in the position of the RBSO, who alone decides who is deserving of punishment; he tells them that everything that happened was ultimately for the best. In her view, Yoisef’s noble conduct is incompatible with the idea that he would have acted out of revenge. And certainly not at the expense of causing anguish to his father. Gishmak, ober do all agree? Not!

Says the Ramban: what motivated Yoisef was a commitment to realize his dreams, which he apparently viewed as prophecy and as Divine guidance for his own conduct. Avada you recall that most of the trouble began when Yoisef shared his dream of dominance over his brothers. Seemingly, Yoisef was determined to make his own dreams come true and therefore put his brothers through various trials and tribulations in order for all his brothers to bow down to him. In Yoisef’s dream (one of them), eleven stars -seemingly representing his eleven brothers- bow before him. Ober, when they showed up without Binyomin, he realized that ten brothers bowing was not enough to make his dream come true. What to do? He called an audible and insisted they bring him along on their next visit. The bottom line: he had no malice. Instead, he had a dream and set about making sure it came true. Ober asks the Ois azoy: we all have dreams; are we then permitted to subject and torment others for our own benefit? Seemingly if you were Yoisef, the answer might be yes.

Ober says Rashi that the words of the posik “Yoisef remembered the dreams which he had dreamed about them,” meant farkert (opposite). “And he knew that they had been fulfilled, for here they were, bowing before him.” In other words: ten brothers bowing was a sign that his dream had come true. Also gishmak, ober, if that’s the case, why concoct a new scheme leading to his brother and eventually his father coming down to see him in Mitzrayim? Shoin, let’s recall that Yoisef -back in Parshas Vayeshev- had two dreams. In the second, his father too was bowing to him. Ober, forcing dreams to come true aside, how can Yoisef’s behavior be explained away? How can we call him a Tzadik when at times he acted without the TZA, if you chap. Moreover, asks the Ramban azoy: After Yoisef had spent many years in Egypt, becoming an officer and supervisor in the house of a great royal minister, how is it that he did not send a single letter to his father to notify him [of his whereabouts and of his situation] and to console him? For Egypt is only a six-day journey from Chevroin, and even if it had been a year’s journey away, he should have sent word to his father, who could easily have redeemed him, with his vast fortune? How then do we insist that Yoisef was but a victim when he had ample opportunity to reveal himself instantly and even before the brothers arrived looking to buy food? Why taka did he not contact his father and tell him he’s alive and well? Were Yoisef’s hands clean? Or, had he already made a clean break from the family, and started a new life for himself?

Shoin, leave it to our sages, new and old, to come up with yet more innovative approaches to whitewash those it likes. Efsher they liked Yoisef because he was a pretty boy and we already established that medrish loved its women. Shoin, that pshat not a medrish but the Ois thinking out loud while flying.

An innovative approach proposed by contemporary scholars, in different variations, seeks to explain Yoisef’s behavior as the result of a prior decision to cut himself off from his brothers and his father’s household, with different reasons offered for this decision. What? Yoisef wanted out of the mishpocho? Too frum for him?

Says R. Yoel bin Nun that Yoisef’s decision was based on a mistake. Yoisef believed that he had been rejected from his father’s household and with good reason. He recalled Yishmoel and Eisav and how they had been pushed out in the preceding generations in favor of their respective brothers. Yoisef efsher believed that in his generation, he was odd man out. His brothers hated, tried to kill him, and his father didn’t come looking for him for over twenty years. Yoisef believed that his sale was undertaken with his father’s knowledge, and that Yaakov had perhaps sent him in the first place to check on his brothers with the intention that they would take care of removing him from the House of Israel. Since Yoisef knew nothing of the brothers’ ruse of dipping his coat in the blood of the ram, he could not understand why his father did not come to redeem him or seek him out – and these thoughts led him to the conclusion that his father was apparently persuaded by his brothers that there was no choice but to force him out, just as Yishmael and Eisav had been forced out. Yoisef therefore reconciled himself with reality as he mistakenly understood it; he decided to rebuild his life outside of his father’s house. Well blow me down! Could this be pshat? Why not? To bolster this theory, he points to Yoisef naming his first born son Menashe. The heylige Toirah tells us he was so named “For God has caused me to forget (nashani) all my toil and all of my father’s house.” Did Yoisef thank the RBSO for being able to put his sorrow and suffering – and his father’s house – behind him? Could be and just as plausible as any other pshat. What really happened? Ver veyst?

Ober listen to this bombshell pshat, avada controversial, among rabbis who won’t ever admit that it’s at all shayich (possible). Says Prof. Yisrael Eldad (Hegyonos Mikra), azoy: Yoisef was efsher the prototype of the “yoired,” the Israeli who leaves Israel and suddenly finds succor for all his troubles and difficulties in a foreign country; he therefore seeks to assimilate in that land and to cut himself off completely from his father’s house, from his heritage, and from his native culture. You hear this Raboyseyee? Yoisef no longer wanted to follow in the ways of his father and forefathers. Says Prof. Eldad that by naming his son Menashe, which reveals Yoisef’s real and genuine aspiration to forget and cut himself off from Yaakov’s household), Yoisef understands that so long as he lived at home, he suffered from his brothers, and so long as he remained faithful to the values and culture of his father’s house, he suffered in Egypt, too. Now that he has shaved off his beard, changed his manner of dress, taken on an Egyptian name, and assumed the position of Paroy’s chief minister, he is able to forget his troubles, his suffering, and his father’s house. The bottom line according to this pshat: Yoisef was completely uninterested in his father and his fate, and he consciously decides to forget him. Grada one medrish tells us azoy: when Yoisef saw that he had achieved this [great success in Potiphar’s house], he began to eat and drink and to curl his hair, and said, “Blessed is God Who has caused me to forget my father’s house.” Yikes! Did Yoisef decide that since there was apparently no hope of returning to his father’s house, that he would assimilate into Egyptian society? Did he hide his identity from his brothers because he had no wish to return to them and to the toil and suffering that he had previously experienced? Ver veyst but something to think about and certainly within reason for any logical person. Having achieved the office of viceroy, second only to Paroy, Yoisef wanted nothing to do with his ancestral home. Yikes!

The bottom line: even if the last pshat was indeed what happened, we need to give Yoisef a pass. In fact, under any pshat, he deserves one. He was an abused teen and traumatized. Abused teens need time and particular trigger events to bring them back and allow them to feel and accept love.

The bottom line: even if the last pshat was indeed what happened, we need to give Yoisef a pass. In fact, under any pshat, he deserves one. He was an abused teen and traumatized. Abused teens need time and particular trigger events to bring them back and allow them to feel and accept love.

How did Yoisef recover from all he endured? Only when Yehuda came forth -as we will read next week- and convey the depths of Yaakov’s sorrow, was Yoisef able to feel love again. He could no longer restrain himself; he reunited with his brothers.

A gittin Shabbis –

The Heylige Oisvorfer Ruv

Yitz Grossman

Source URL: https://oisvorfer.com/miketz-2020-the-vicissitudes-of-life/