Bereishis 2025: The First Ever Murder Mystery – Who, When, How… and Why?

by devadmin | October 16, 2025 11:37 pm

Raboyseyee and Ladies,

The First Ever Murder Mystery: Who, When, How… and Why?

“Long before O.J. got away with murder, back in year one, the first ever homicide took place — and the killer walked! No Netflix docuseries, no Dateline special, no Nancy Grace shouting ‘Monster!’ on TV — just the RBSO handling the investigation Himself.” More on that below but we start here.

Let’s set the scene: Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, the case is simple: one brother killed another. But the questions keep piling up: Why? When? How? And—why did RBSO give him a second chance?

Welcome to Parshas Bereishis which features creation of the world, the animal kingdom, humankind, and the heylige Toirah’s first murder mystery. Well, sort of. Unlike the whodunits of today dating back only a few hundred years, in this first murder case, both the perpetrator and victim are obvious, but every other detail is frustratingly laconic and vague.

Unlike Toirah inspired entrepreneurs who read the pisukim and discover new business opportunities instantly and forever, it would take thousands of years for the goyish writers to figure out this genre and the great business opportunities in whodunit books and made for TV -or movie- scripts. According to informed sources, the first writers in this genre include these people:

| Year | Author | Work | Importance |

| 1748 | Voltaire | Zadig | Early proto-detection |

| 1819 | E.T.A. Hoffmann | Mlle de Scuderi | First murder mystery |

| 1841 | Edgar Allan Poe | The Murders in the Rue Morgue | First true detective story |

| 1868 | Wilkie Collins | The Moonstone | First full detective novel / whodunit |

In our parsha, back in year one or maybe in year 15, we know the crime. Of course there is a machloikes as to how old Kayin was when he committed the first murder. Some say it happened the day they were born, others that Kayin was 15. We know the victim. But beyond that? The trail is cold, the motive unclear, the weapon… missing. And the divine judge, the RBSO, the ultimate CSI, has left the file open for centuries. Even the Toirah itself seems to say: “We’ll tell you who, but the rest? You figure it out.” Generations of sages, exegetes, midroshim, and aggadists have tried. Some with brilliance, others with sheer imagination.

Shoin, now, let’s revisit the crime scene. In fact, let us read the relevant pisukim from when Kayin and Hevel (Cain and Abel) were born until the first ever murder recorded in heylige Toirah: Bereishis 4:1–11

וְהָאָדָם יָדַע אֶת חַוָּה אִשְׁתּוֹ, וַתַּהַר וַתֵּלֶד אֶת קַיִן, וַתֹּאמֶר קָנִיתִי אִישׁ אֶת ה’;

English: And Adam knew Chava his wife, and she conceived and bore Kayin, and she said, “I have acquired a man from Hashem.”

וַתֹּסֶף לָלֶדֶת אֶת אָחִיו הֶבֶל; וַיְהִי הֶבֶל רֹעֶה צֹאן, וְקַיִן הָיָה עֹבֵד אֲדָמָה.

English: And again she bore his brother Hevel. And Hevel became a keeper of sheep, and Kayin was a tiller of the ground.

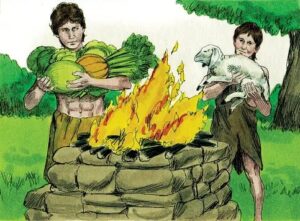

וַיְהִי, מִקֵּץ יָמִים, וַיָּבֵא קַיִן מִפְּרִי הָאֲדָמָה מִנְחָה לַה’;

English: In the course of time, Kayin brought an offering of the fruit of the ground to Hashem.

וְהֶבֶל הֵבִיא גַם-הוּא מִבְּכֹרוֹת צֹאנֹו וּמֵחֶלְבֵהֶן; וַיִּשַּׁע ה’ אֶל-הֶבֶל וְאֶל מִנְחָתוֹ;

English: And Hevel also brought of the firstborn of his flock and of their fat. And Hashem regarded Hevel and his offering.

וְאֶל-קַיִן וְאֶל מִנְחָתוֹ, לֹא שָׁעָה; וַיִּחַר לְקַיִן מְאֹד, וְנָפְלָה פָּנָיו.

English: But for Kayin and his offering, He did not regard them. And Kayin became very angry, and his countenance fell.

וַיֹּאמֶר ה’ אֶל-קַיִן: לָמָּה חָרָה לָךְ, וְלָמָּה נָפְלָה פָּנֶיךָ?

English: And Hashem said to Kayin, “Why are you angry, and why has your countenance fallen?”

הֲלוֹא אִם-תֵּיטִיב, שְׂאֵת; וְאִם-לֹא תֵיטִיב, לַפֶּתַח חַטָּאת רֹבֵץ, וְאֵלֶיךָ תְּשׁוּקָתוֹ; וְאַתָּה תִּמְשָׁל-בּוֹ.English: “If you do well, will you not be accepted? And if you do not do well, sin lies at the door; and to you is its desire, but you must master it.”

וַיְהִי, בְּהִתְהַצְּאוֹתָם בַּשָּׂדֶה, וַיָּקָם קַיִן אֶל-הֶבֶל אָחִיו, וַיְהִי בּוֹ.

English: And it came to pass, when they were in the field, that Kayin rose up against Hevel his brother and killed him.

וַיֹּאמֶר ה’ אֶל-קַיִן: אַיֵּה הֶבֶל אָחִיךָ? וַיֹּאמֶר: לֹא יָדַעְתִּי; הֲשֹׁמֵר אָחִי אָנֹכִי?

English: And Hashem said to Kayin, “Where is Hevel your brother?” He said, “I do not know; am I my brother’s keeper?”

וַיֹּאמֶר: מֶה-עָשִׂיתָ? קוֹל דְּמֵי אָחִיךָ, צֹעֲקִים אֵלַי מִן-הָאֲדָמָה.

English: And He said: “What have you done? The voice of your brother’s blood cries out to Me from the ground.”

וְעַתָּה אָרוּר אָתָּה מִן-הָאֲדָמָה, אֲשֶׁר פָּצְתָה אֶת-פִּיהָ לְקַבֵּל אֶת-דְּמֵי אָחִיךָ מִיָּדֶךָ.

English: And now you are cursed from the ground, which has opened its mouth to receive your brother’s blood from your hand.

What do we know?

- The Perpetrator: Kayin

- The Victim: Hevel

- The Location: A field — outdoors, no witnesses

- The Weapon: Unknown; possibly hands, maybe a stone

- The Motive: Unknown, ver veyst?

On the murder weapon, says Rashi, azoy: “לא ידע קין להכותו; הכה בו עד שהגיע לגרון”

“Kayin did not know how to strike; he struck until he reached the throat.” Seemingly, Kayin beat the hell out of Hevel until the job was done; until he was mamish dead! The bottom line: Even the murderer was improvising. One thing is certain: no murder weapon was found at the scene; a gun he did not have or use. “To be fair, this was the first murder — no YouTube tutorial, no ‘How to Get Away with Murder’ mini-series. The man was winging it.”

Is this why Divine mercy came into play? No concrete weapon, no forensic proof. More on this theory later. The first CSI failure recorded in history. Oib azoy, the case being that we never knew with certainty how Hevel was killed, we can ask this: What was Kayin’s motive? What to do when the heylige Toirah left us guessing? Enter our sages who left us with a banquet of possibilities, from the practical to the mystical to the outright ludicrous. Let’s see what a few had to say. The Toirah gives us this fact: Kayin rose up and killed Hevel. But the why? Ah, that’s where the sages, commentators, and imaginative storytellers have feasted for centuries. Let’s consider some of the juiciest possibilities.

First, the most obvious: Jealousy over the RBSO’s favor. In a classic case of sibling rivalry -the first ever- Kayin’s ego was bruised. Kayin labored the soil, carefully tending his crops, and brought what he thought was a worthy offering. Hevel, the sweet, innocent shepherd, brings the firstborn of his flock with the fat, and the RBSO smiles on him. The heylige medrish (Bereishis Rabbah) notes that Kayin’s heart “was very angry” (וַיִּחַר לְקַיִן מְאֹד), his countenance fallen. Can we blame him? Can you imagine? You slave under the hot sun, schvitzing mamish with sweat dripping into the dirt, and the Almighty nods to your brother instead of you! It’s the oldest story in the book: rejection plus envy equals explosive anger. One can almost hear Kayin muttering, “Why him? Why not me?” Is that why Kayin killed his only brother? Ver veyst? One thing is certain: There have been many thousands of copycat murders by those suffering from uncontrollable jealousy. This pshat is logical but let’s check another possibility.

Or, was it a case of classic sibling rivalry? Even in a world with only a handful of people, human competitiveness rears its head. At times, that head is ugly. Perhaps Kayin and Hevel quarreled over land, pasture, or who got the best corner of the field. The heylige Toirah doesn’t spell it out, but the midrashic imagination fills in the gaps: Kayin, walking past Hevel’s sheep, scowling, muttering under his breath, feeling the tension of resource ownership. In other words, the human propensity to squabble didn’t require civilization, money, or democracy — just two brothers, a field, and fragile egos. Let’s recap this pshat: the entire world population at that point consisted of exactly four people — Adam, Chava, Kayin, and Hevel — and already, they couldn’t get along?! Mamish unbelievable! The ink had yet to dry on Creation, and one brother has already committed a homicide. We can chap were this to happen on a typical Friday or before Yom Tov on Central Avenue but Gan Eden was devoid of traffic with plenty of space for everyone. But no, even Gan Eden had its real estate squabbles. Maybe what they needed back then was a good-maker like President Trump. He could’ve called it “The Abraham Accords, Prequel Edition”: two brothers, one land, and a peace deal sealed with a handshake or some chicken scratch on a stone tablet, ver veyst? Perhaps it would have earned him his first Nobel Peace Prize before there was even a Nobel! Instead, the heylige Toirah’s peace prize went to Pinchas who killed two people? What’s pshat? Ober, let’s not get out in front of our skis; that story is months away. Nice pshat, ober was that the motive for the killing? Let’s explore a few more.

And now, the juicy, spicy one: romantic jealousy. Believe it or not, a few midroshim suggest that the brothers might have quarreled over women, perhaps their twin sisters. Twin sisters? Where did they come from? Why weren’t they mentioned as being born to Adam and Eve? On the other hand, nor does it say they were not! Shoin! That lacuna allowed the medrish to get creative; it’s what they do best! That storyline for another day, ober let’s play it out. Picture this: Kayin pacing the field, Hevel laughing with someone, maybe a sister whose heart he coveted. Some medroshim mamish imply that even the first family had love triangles and flirtations. Human desire, it seems, is eternal, and jealousy over affection can provoke deadly outcomes. Some might call it scandalous; others call it timelessly relatable. “He looked at her… she smiled at him… and shoin. Jealousy ignited a fire that no crop or offering could quench.” Ober, what sisters? What’s happening here with this pshat? Let’s dig deeper.

A few midroshim speculate that Odom and Chava’s first children were twins, possibly multiple sets, though the heylige Toirah doesn’t explicitly say so. In that reading, Kayin might have been interested in a girl (a sister, naturally — in those first generations this was how the population grew). Hevel might have been favored by the same sister, or simply more charming, more accepted, or better at winning her attention. Even if each had their own twin, jealousy could still arise over perceived affection or attention. Kayin may have felt that Hevel’s personality, spiritual success, or general charisma made him the “preferred” brother in the eyes of their sisters. In the medrish, this type of “romantic jealousy” hints to illustrate the naturalness of envy and the dangers of unchecked desire. Ober, let’s dig further into the medrish (Bereishis Rabbah 22:7) which offers this possibility: Kayin was born with a twin sister, while Hevel was born with two twin sisters. Each brother married one of the sisters born with him. However, they both desired to marry the third sister – a threesome- leading to their conflict and ultimately to Kayin’s act of murder. The bottom line: Even in the first generation, romance jealousy might have caused murder. Not much has changed.

Another medrish adds even more color and imagination: let’s check out Medrish Tanchuma (Bereishis 9) which proffers this: Kayin’s jealousy stemmed not only from the acceptance of Hevel’s offering but also from the perceived favoritism in matters of marriage and inheritance. Not much has changed there either.

And Targum Yoinoson (Bereishis 4:8), what says he? He provides a paraphrased explanation of the events, indicating that Kayin’s anger was fueled by a sense of injustice, feeling that the world was not governed by merit, leading to his confrontation with Hevel.

Says Rav Zadok HaKohen azoy: Kayin’s hatred towards Hevel was not only due to the acceptance of Hevel’s offering but also because Hevel’s twin sister was exceptionally beautiful, and Kayin desired her. This desire intensified his jealousy and contributed to his decision to kill Hevel. Beauty to kill for! The bottom line: These sources collectively paint a picture of Kayin’s complex emotions, where spiritual jealousy intertwined with personal desires, leading to tragic consequences. It’s all real!

The next possibility is a philosophical dispute. Pirkei de-Rabbi Eliezer (21) dramatizes the brothers as representatives of opposing beliefs: Kayin, the skeptic, denying the afterlife and divine justice; Hevel, the faithful, trusting in the RBSO’s plan.

Kayin: “אין עולם הבא ואין דיין ואין גמול”—Hevel: “יש”

A debate about eternal truths escalated into a tragic conclusion. Perhaps Kayin felt that Hevel’s righteousness mocked his own disbelief — a theological clash that became too hot to handle. The bottom line: It was the first theological debate gone violent. Thousands of years later, people are still being killed for the same reasons.

For those who enjoy the mystical side, the cosmic explanation is compelling. The heylige Zoihar presents Kayin and Hevel as forces of the universe itself — Kayin embodies gevurah (severity), Hevel chesed (kindness). Their clash isn’t just human; it is cosmic, a first expression of imbalance in creation, showing that sometimes violence mirrors spiritual tension. The murder becomes both literal and symbolic, teaching that even physical acts have metaphysical echoes. What that means, ver veyst but of course we cannot leave out the Zoihar.

Believe it or not, there are more theories but you get the point. Why did Kayin kill Hevel? Ver veyst? The final bottom line on all the theories is this: We will never know for sure. The first murder remains unsolved, open to interpretation, and eternally instructive. Ego, jealousy, and rage are timeless. Kayin did it. Hevel died. The world was small, egos were big, and the mystery remains. And somewhere, maybe, a modern mediator with sharp negotiation skills could have rewritten history. That being said, one thing is zicher: He killed him in cold blood but the RBSO gave Kayin a pass and the question is why?

Why was Divine mercy shown? Why did Kayin survive? Taka excellent questions. After the first-ever murder in human history, the RBSO’s reaction was surprisingly merciful. Kayin confesses (“Gadol avoni minso”), and instead of immediate destruction, the RBSO places a protective “sign” upon him so that no one will kill him. We know this as ‘the mark of Cain. Why? Over the centuries, many sages and others have grappled with this divine leniency. They have proffered a wide range of explanations for why the RBSO forgave (or at least spared) Kayin. Does anyone know with certainty? Not! Let us review what some said.

Says the Medrish (Tanchuma Bereishis 9) and Pirkei de-Rabbi Eliezer 21 that since there had never been a killing before, Kayin had no model or precedent to understand the full consequence of taking a life. And says the Ramban (to Bereishis 4:13) that the RBSO treated Kayin with relative mercy because humanity was still “new” — moral boundaries were only being established. In other words: the RBSO’s leniency was part of humanity’s “training period.” The world was still in beta testing. Kayin didn’t know the rules yet. As an aside, the people failed beta and by next week, the RBSO will have decided to start over.

Of course, some suggest Kayin got a pass because he did tshuva! Says the medrish (Midrash Rabbah 22:13) that Kayin’s words “Gadol avoni minso” are interpreted by some as a confession — “My sin is too great to bear.” The medrish also says this: When Odom heard Kayin’s confession and saw that his teshuvah was accepted, he too began singing Mizmor shir leyom haShabbis, later a song popularized by the master, Shlomo Carlbach, OBM. The bottom line: Kayin confessed and did teshuvah. Kayin complained, cried, repented, and lo and behold, the RBSO accepted it. Not bad for the world’s first murderer! The man went from “Most Wanted to Most Forgiven.” The first baal teshuvah. Ladies and gentlemen: Kayin kills Hevel, gets forgiven, and Odom is inspired to sing zemiros. Only in the heylige Toirah.

And says the heylige Zoihar (Bereishis 22b) that Kayin repented sincerely and accepted his punishment. The RBSO, seeing genuine remorse, lessened the severity. The bottom line moral of the story: He was the first murderer — but also the first real baal teshuvah. Ober the Radak (Bereishis 4:15) points out that Kayin lived before Matan Toirah, before any command prohibiting murder was given. The basic moral laws were not yet fully formalized. The RBSO didn’t hold Kayin to a legal standard that hadn’t yet been declared. The bottom line: There was no “Thou shalt not kill” plaque hanging in Gan Eden yet.

Says Rashi (4:15) citing the medrish (Tanchuma) that the RBSO put a “sign” on Kayin not as a pardon but as protection — to give him time to wander, reflect, repent, and serve as a living cautionary tale. And the Sforno says that sparing Kayin allowed humanity to survive and multiply. Had the RBSO wiped him out, Adam and Chava -having lost Hevel- would have been left childless again. Kayin was allowed to live not because he was innocent — but because the RBSO wasn’t done with humanity yet.

Another medrish (Midrash Tehillim 9:12) emphasizes the RBSO’s middas haRachamim: mercy precedes justice, even when justice would demand retribution. And this was the first time the RBSO’s attribute of mercy was publicly revealed in the Toirah.

Rashi and Malbim tell us about Kayin’s punishment. Let’s read the posik innaveynig: כִּ֤י תַֽעֲבֹד֙ אֶת־הָ֣אֲדָמָ֔ה לֹֽא־תֹסֵ֥ף תֵּת־כֹּחָ֖הּ לָ֑ךְ נָ֥ע וָנָ֖ד תִּֽהְיֶ֥ה בָאָֽרֶץ׃

“If you till the soil, it shall no longer yield its strength to you. You shall become a ceaseless wanderer on earth.” Being condemned to wander, homeless and cursed from the ground — was a fate worse than death. The RBSO told him, “Na v’nad tihyeh — you’ll wander the earth.” In modern terms, He sentenced him to a lifetime of flying only on Spirit Airlines middle seats. No house, no shul membership, no frequent flyer miles, just endless exile and people avoiding you at kiddush. Some mercy! The medrish (Midrash Rabbah 22:12) compares his wandering to being cut off from all human contact; the RBSO didn’t need to kill him — he’d already destroyed his own peace of mind. The bottom line: Sometimes the living punishment is the harsher one.

And this reality check: According to Targum Yoinoson and another medrish (Midrash Aggadah), the “sign” on Kayin protected him only for seven generations — until Lemech would ultimately kill him. Mercy — yes; amnesty — no. The bill came due later. The RBSO’s justice was delayed, not cancelled

On the other hand, let’s check out the heylige Zoihar who says this: the RBSO forgave Kayin partly so that later sinners wouldn’t despair. If the very first murderer could be given a chance to atone, no sinner could ever claim, “There’s no way back.” In other words, Kayin’s survival was the RBSO’s opening lesson in hope.

Shoin, let us close this expanded post with a few words on the missing murder weapon: Some midroshim tell us Kayin didn’t even know how to kill. Kayin killed Hevel “by accident,” not realizing the blow would kill. He kept hitting different parts of Hevel until he learned where death lay. In other words, there was no intent to kill. In that case, the RBSO’s mercy may have reflected that lack of intent — involuntary manslaughter in the world’s first case file. Maybe that’s why the RBSO gave him a break — no weapon, no premeditation, no motive sheet, and the harshest charge dismissed! The RBSO as the first merciful judge: “Okay, Kayin, you’re guilty, but I’ll give you probation. Seven generations of wandering should do it.”

The bottom line: What do we know now? That the RBSO did not tell us why He had rachmunis (mercy) on Kayin. As to a rationale, we have many choices to pick form; pick the pshat that talks to you and satisfies your need to understand. Who said we need to chap the RBSO’s was?

Kayin was spared either because:

- Humanity was still learning what sin meant,

- He confessed and repented,

- There was no legal precedent,

- The RBSO wanted to demonstrate mercy,

- The punishment of exile itself was worse than death,

- And — perhaps most profoundly — the RBSO wanted the world’s very first sinner to prove that teshuvah works.

Picture the scene: The first-ever courtroom drama — no lawyers, no jury, no CNN coverage, just Kayin standing before the RBSO. No forensics, no DNA, no ring camera footage, not even a body count expert — just a shocked family and the RBSO doing the questioning. “Kayin, where’s your brother?” And Kayin gives the line of the century: “Am I my brother’s keeper?” Chevra, the man just invented sarcasm! First murder, first lie, first deflection — the trifecta of human nature.

And so, raboyseyee, the world’s very first criminal trial ended not with an execution, but with a commutation. Kayin, the original bad boy, walked. Just him, his conscience, and a mark on his forehead. You could say, quite literally, he was the first person in history to get away with murder. Maybe that’s where the expression comes from! Perhaps that’s why the RBSO let him live — not to reward him, but to teach us that you can fool people, but you can’t fool Heaven. The RBSO sees it all. Still, in the annals of human history, Kayin gets the dubious honor of inspiring the phrase “getting away with murder” — proving that even when you do, you never really do. The guilt, the wandering, the divine ankle monitor — it’s all there.

On the other hand, the man killed his only brother, talked his way out of it, and then went on to build a city and start a family. That’s quite the second chance and career turnaround.

A gittin Shabbis and a Gittin upcoming new Choidesh.

The Heylige Oisvorfer Ruv

Yitz Grossman

Source URL: https://oisvorfer.com/bereishis-2025-the-first-ever-murder-mystery-who-when-how-and-why/